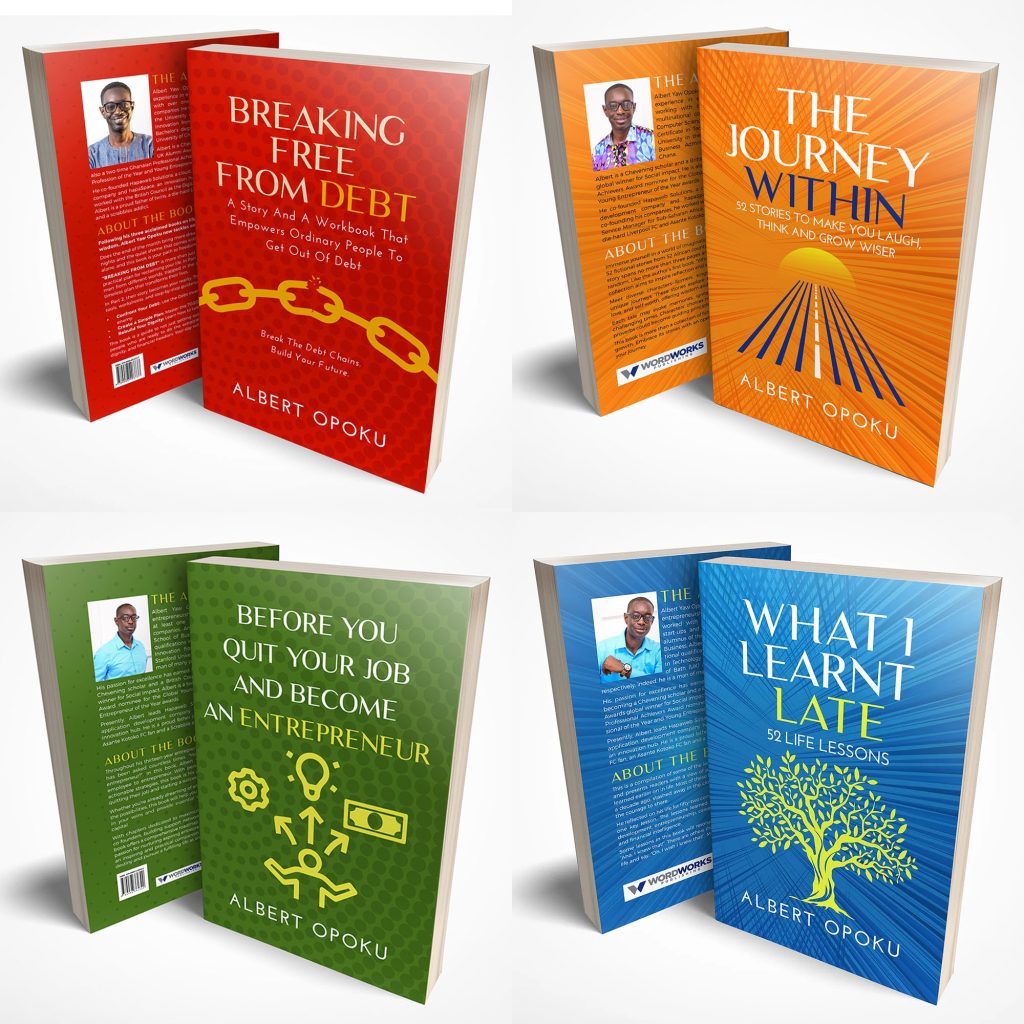

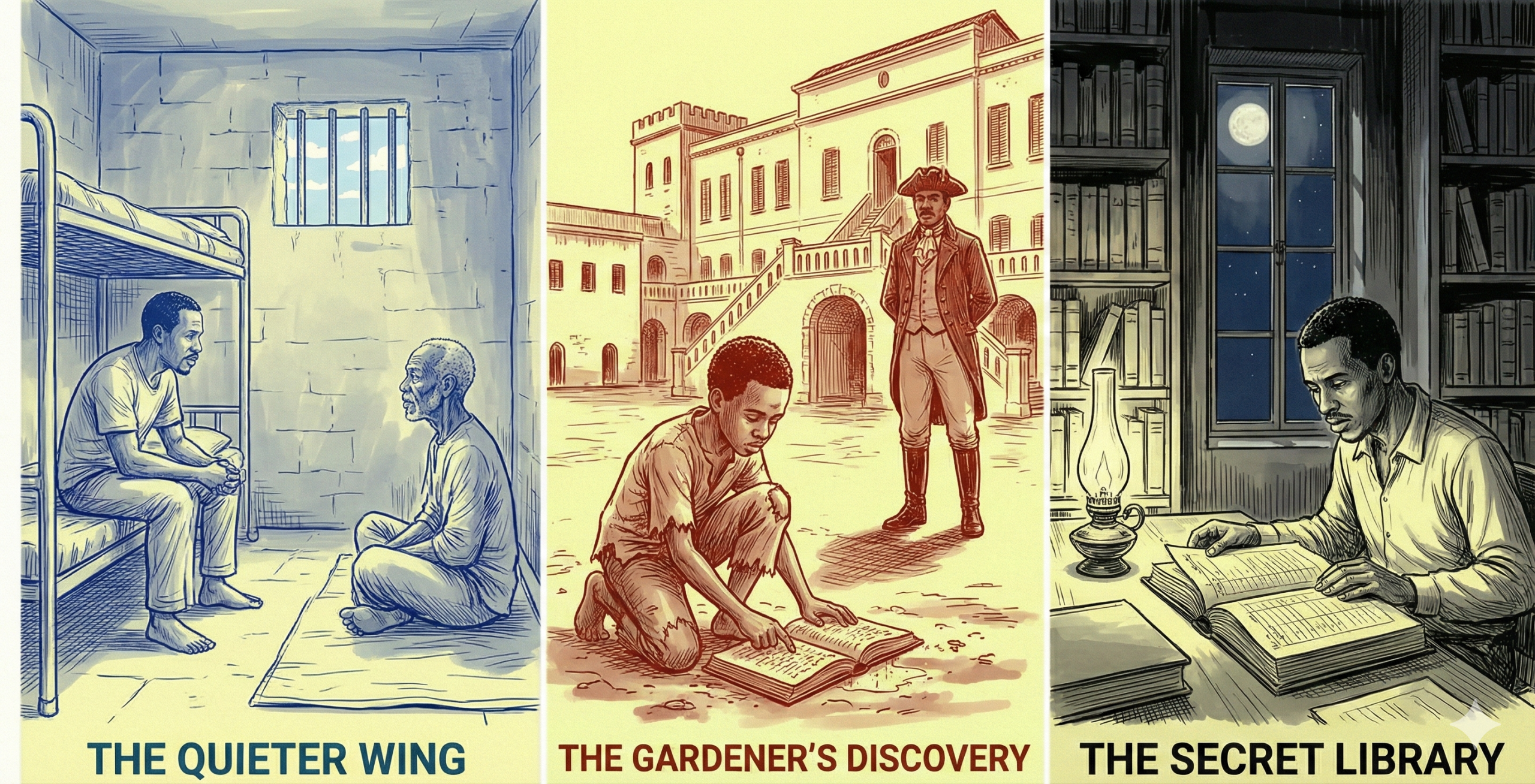

“It was a Friday night in Kumasi,” Forson began, his voice becoming low and weighted with a different kind of sorrow. “Six years ago. I had been invited to a wedding anniversary of an old friend, a fellow teacher from the Nkrumah days. We had eaten well, and yes, we had drunk too much gin and ginger. We were celebrating the fact that we were still alive, still breathing the air of a democratic Ghana.”

He gripped the edge of his mat. “The drive from Suame to Kwadaso is short, but that night, the road felt long and treacherous. I was seventy-eight years old, my eyes were tired, and the gin was a thief of my reflexes. I remember the glare of headlights from a passing tro-tro. I remember swerving to avoid a pothole. And then, I remember the sound.”

Kwesi watched Forson’s face, seeing the raw agony of the memory. “The sound of impact. Not of metal on metal, but of metal on bone. Two women were walking home from the market, balancing their last wares of the day. I never even saw them, Kwesi. One moment there was a clear road, and the next, there were screams that still wake me up at three in the morning.”

Forson bowed his head. “They died before the ambulance reached the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital. They were mothers, sisters, daughters. In a few seconds of negligence, I had erased two lives and shattered two families. The judge was fair. Manslaughter. Ten years. Because of my age and my history, he showed mercy.”

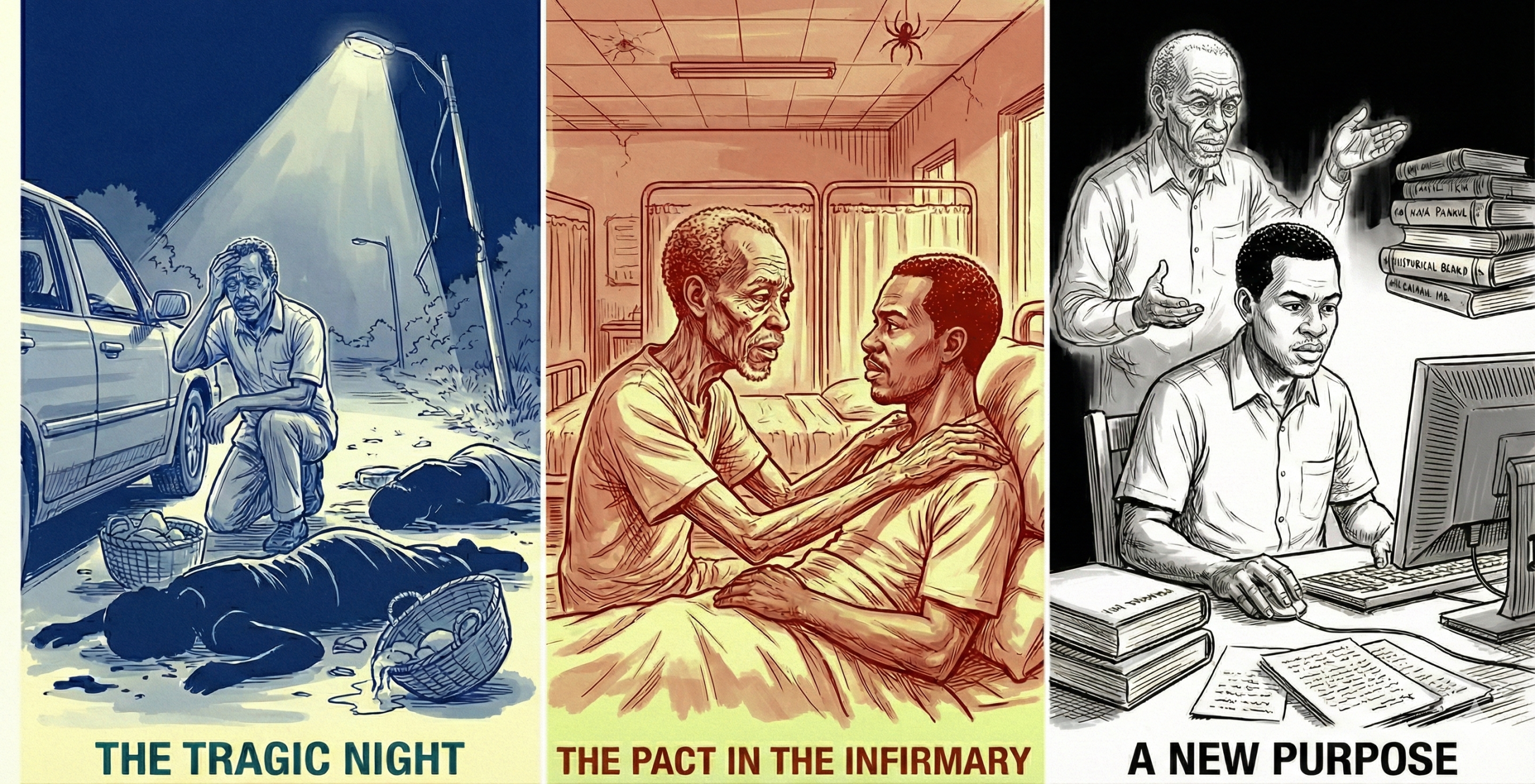

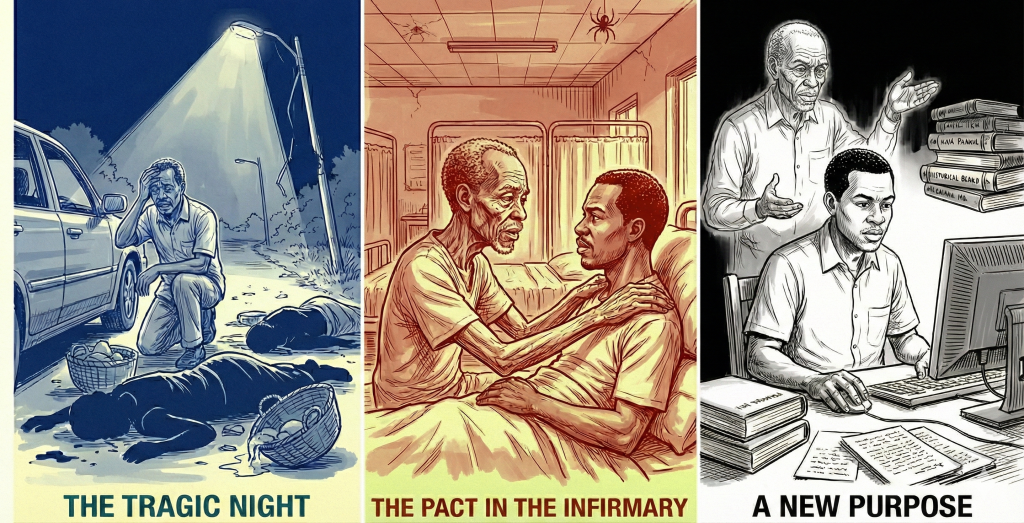

He looked up, his eyes wet but clear. “I have been here for six years. My body is failing me. This diabetes is a slow poison, and my heart skips beats as if it’s looking for a way out. But I refuse to die in this infirmary, Kwesi. I will finish this ten-year sentence, even if I have to crawl to the gate on my last day. I owe it to those women. And I owe it to the boy who once sat in Lord Turman’s library.”

Old Man Forson reached across the space between their bunks, his hand finding Kwesi’s shoulder. It was a fragile grip, but it felt like steel. “You want to die because a woman married your cousin? Look at me. I have lived through the fall of an empire, fourteen years of exile, and the killing of two innocents. I am eighty-four, and I am still fighting for every breath.”

“Think of your father, Opanyin Dankwa,” Forson urged. “If you die here, you kill him too. You are the only truth he has left. You must survive, young man. Not just to reveal the truth, but for the legacy of the name you carry. I will mentor you. I will teach you the things I have learned over eighty years, and I will teach you the things I learned in the corridors of the Castle. But you must promise me one thing.”

“Anything,” Kwesi whispered.

“You must go back to your studies,” Forson commanded. “The computer lab, the banking modules, the criminology. We will combine your digital tools with my historical wisdom. We will build a mind that can see the Asamoah trap before they even set it. I will finish what Turman started in me, but I will do it through you.”

Kwesi felt a surge of purpose that he hadn’t felt since the day of his arrest. The apathy that had nearly claimed him was receding, replaced by a cold, sharp discipline. He looked at the old man, this relic of a lost era, and realised he wasn’t looking at a fellow prisoner. He was looking at a map.

“I promise,” Kwesi said, his voice firm.

“Good,” Forson smiled. “Now, go and find Officer Owusu. Tell him the Librarian is ready to return to work. We have a lot of history to rewrite, and very little time to do it.”