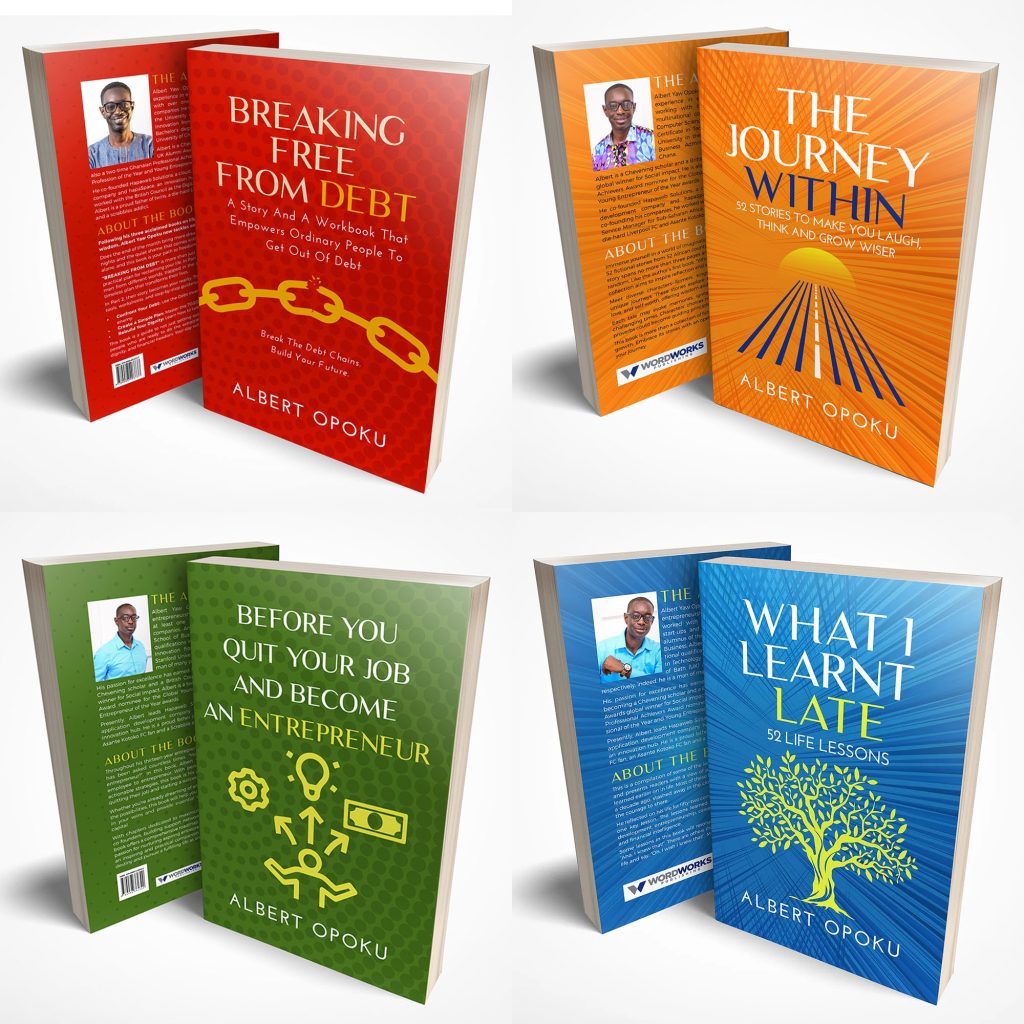

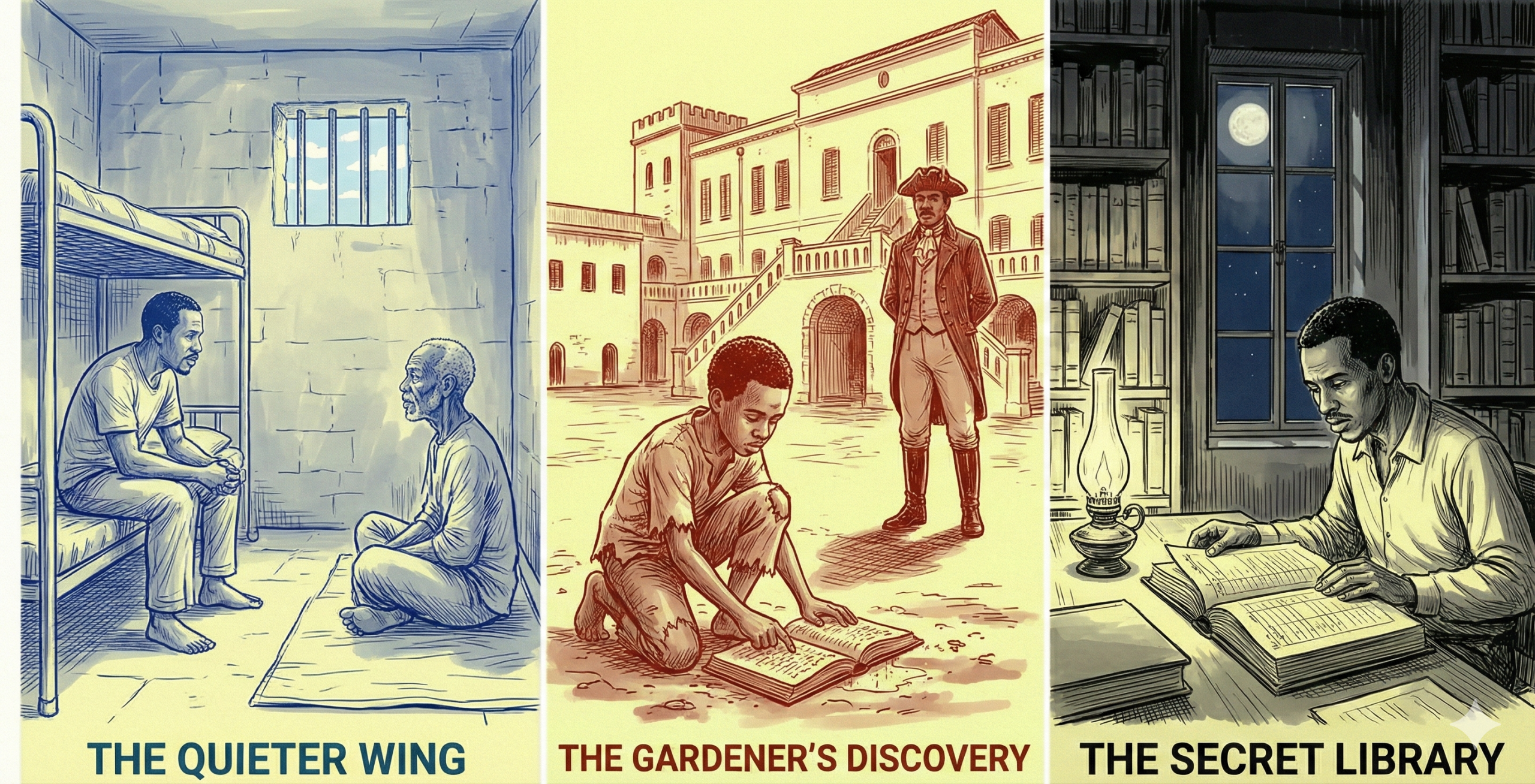

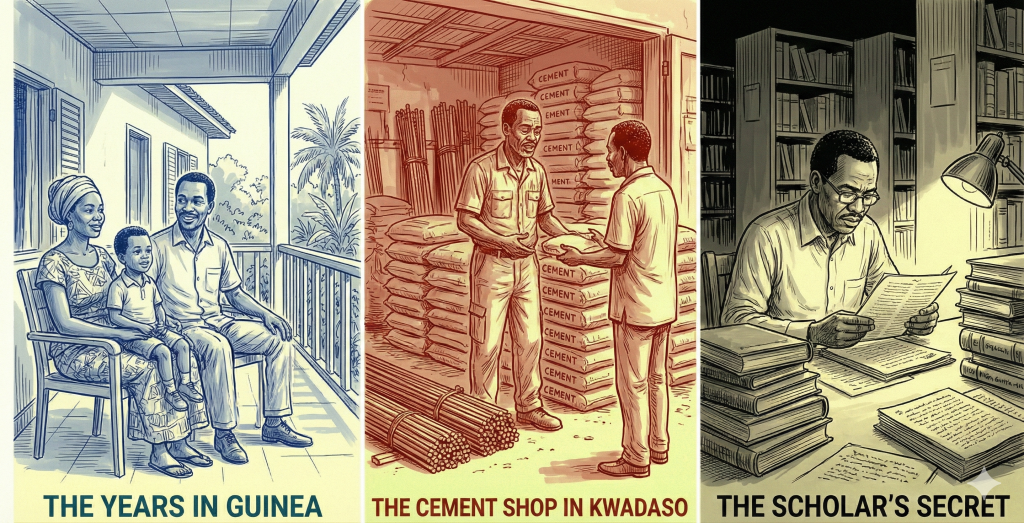

“Guinea was a land of interesting people and French grammar,” Forson said, his voice trailing off into a distant, dusty memory. “We arrived in Conakry as the ‘honoured guests’ of Sékou Touré, but in reality, we were the living reminders of a dream that had failed. For fourteen years, I lived in a small villa on the outskirts of the city. I learned to speak French with a Guinean lilt, and I learned to survive on the meagre stipend the government provided.”

He looked at his hands, turning them over as if searching for something. “In those years of exile, I tried to build a life. I met a woman, Mariam. She was a teacher, a woman of grace who didn’t care about the politics of the Castle. We had a son, Jean-Luc. For a while, the pain of the coup was a distant ache, replaced by the warmth of a home.”

Forson’s eyes dimmed. “But an exile’s life is built on shifting sand. When Nkrumah died in 1972, the protection we enjoyed began to fray. I stayed for Jean-Luc, working as a translator, waiting for the wind in Ghana to change. It took a long time, Kwesi. Long enough for a new generation to forget the names of the men who went to Beijing.”

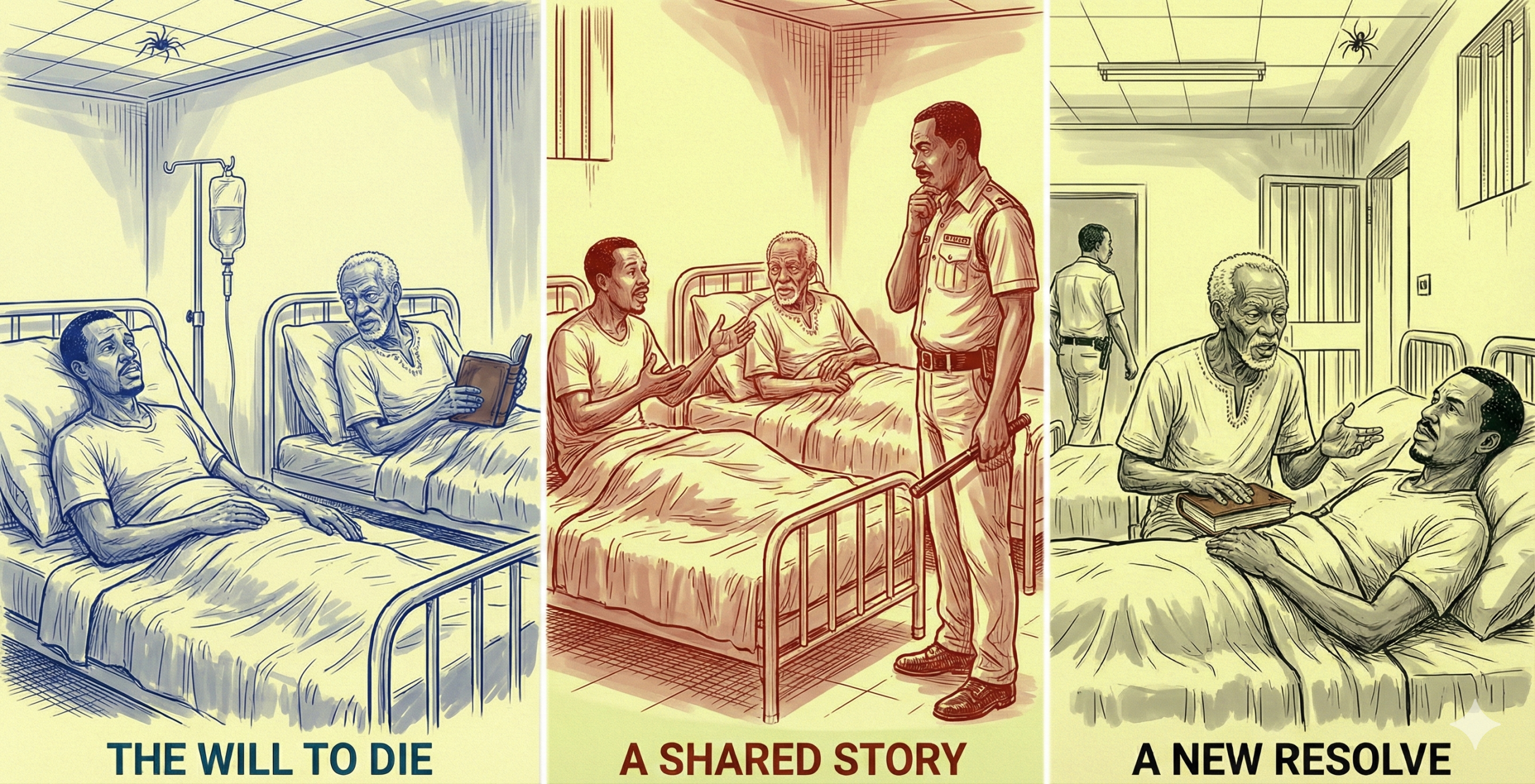

“When did you come back?” Kwesi asked.

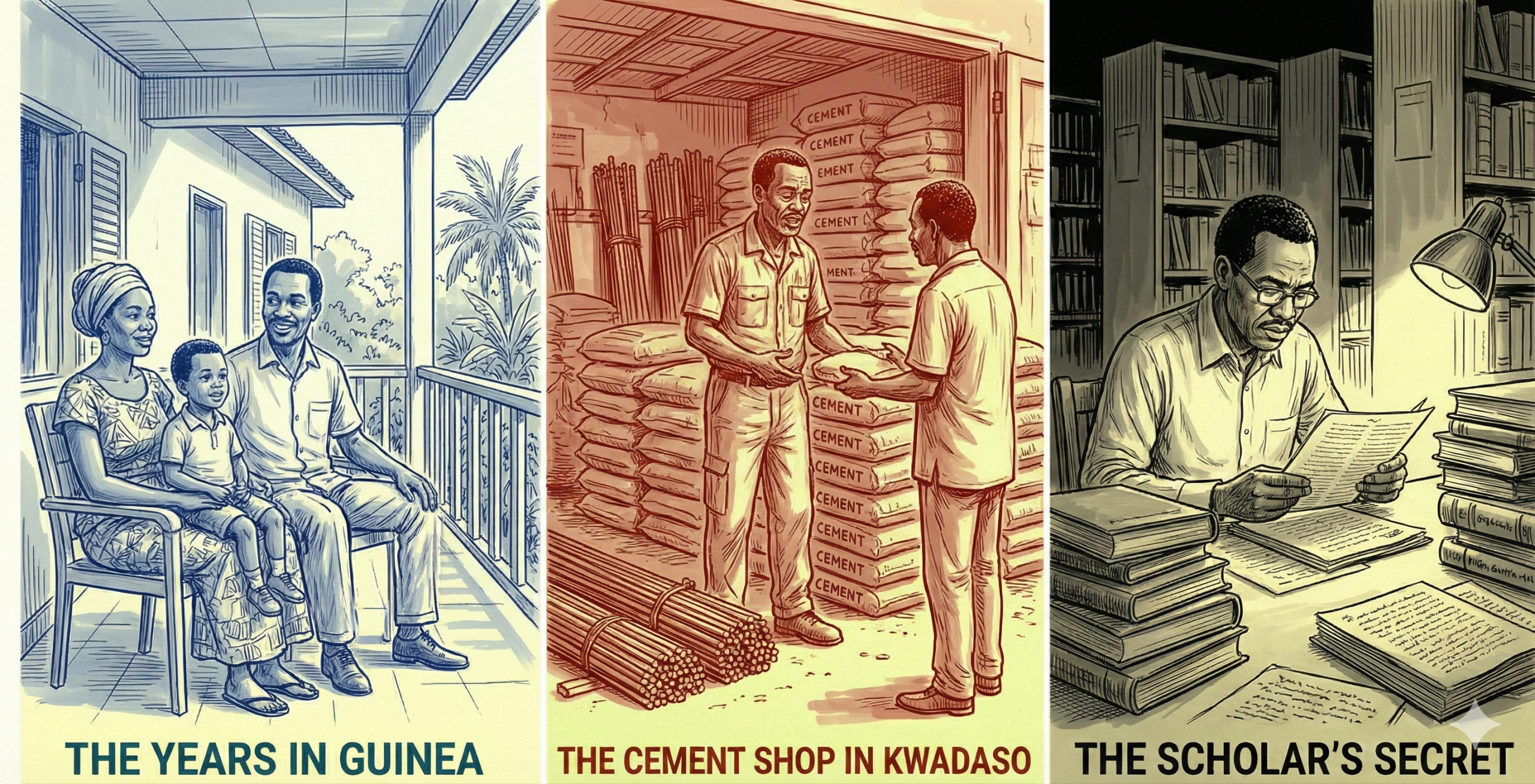

“1984,” Forson replied. “The Rawlings era was in its stride. The revolutionary fervour had cooled into a pragmatic kind of governance. I decided it was time to come home. But the return was more painful than the departure. I had been gone so long that I was a stranger in my own language. My family in the village was gone; the Pra River had flooded their lands and their memories.”

He paused, a flicker of profound regret crossing his weathered face. “The hardest part was leaving Mariam and the boy. I told myself I would go back to Ghana, find a footing, and send for them. But the Ghana I returned to was broke, wrestling with economic recovery programmes. I moved to Kumasi, hoping to disappear into the bustle of the Garden City. I started a small building materials shop in Kwadaso, selling cement and iron rods to men who were building a future I no longer belonged to.”

“Did you ever find them? Jean-Luc and Mariam?”

Forson shook his head slowly. “I tried. I wrote letters that never arrived. I saved every cedi to travel back, but life has a way of stealing your time while you are busy counting your money. By the time I had the means, the borders were tight, and the addresses I had were gone. I lost touch with my own blood, Kwesi. That is the true sentence of the exile, to be a stranger in the land of your birth and a memory in the land of your heart.”

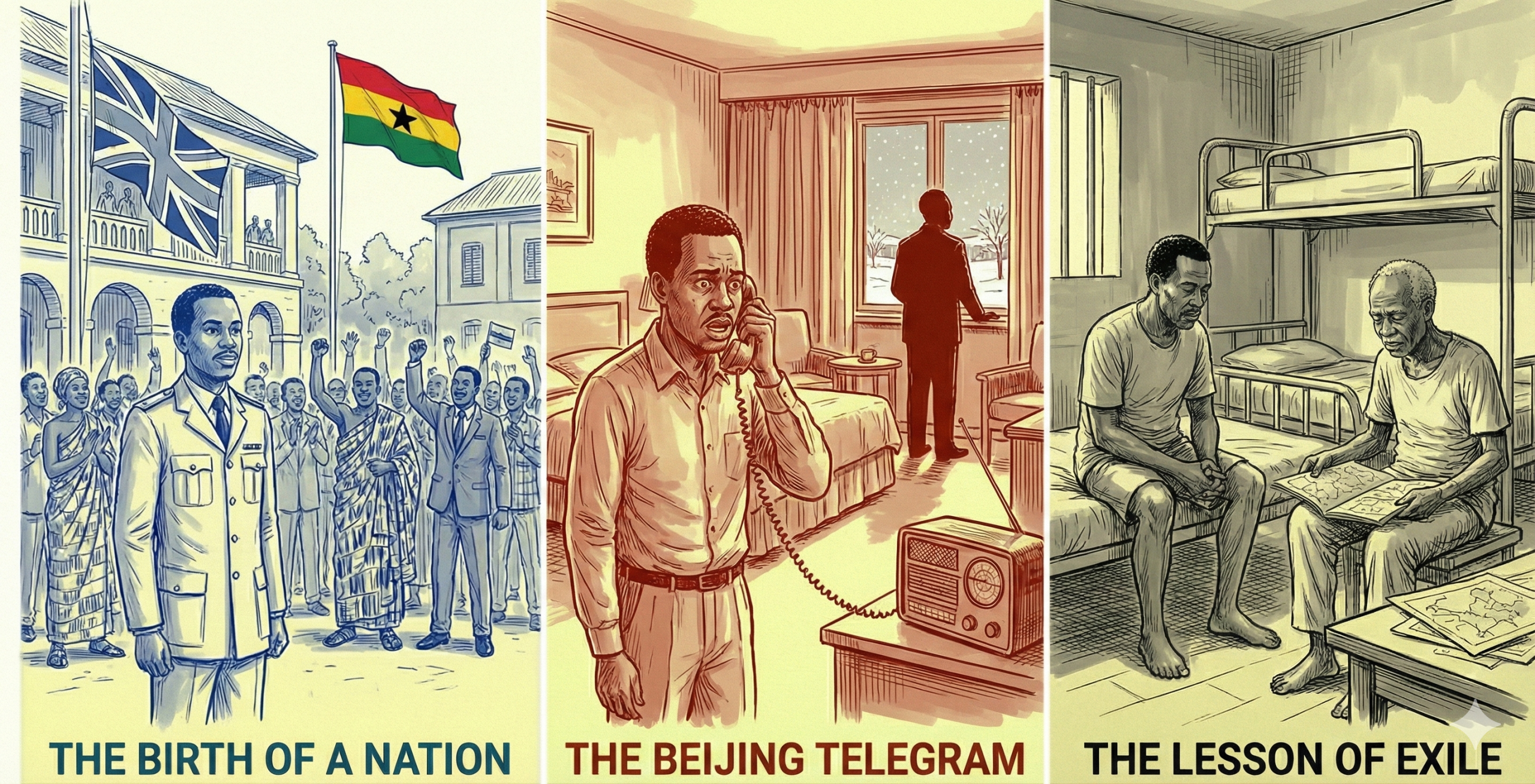

“In those years in Kwadaso, I also worked as a freelance history researcher,” Forson added, a small, proud smile returning. “I spent my weekends in the archives of the Manhyia Palace and the libraries of KNUST. I was a shopkeeper by day and a scholar by night, still looking for the secrets inside the paper. I thought I had found peace in the quiet rhythm of the cement bags and the history books.”

He leaned back, his joints popping. “But as the Akan say, ‘the path you take to avoid your is the very path that leads you to it.’ I survived the British colonial power, I survived the coup, and I survived the exile. I thought I was safe. But the world wasn’t finished with me yet.”