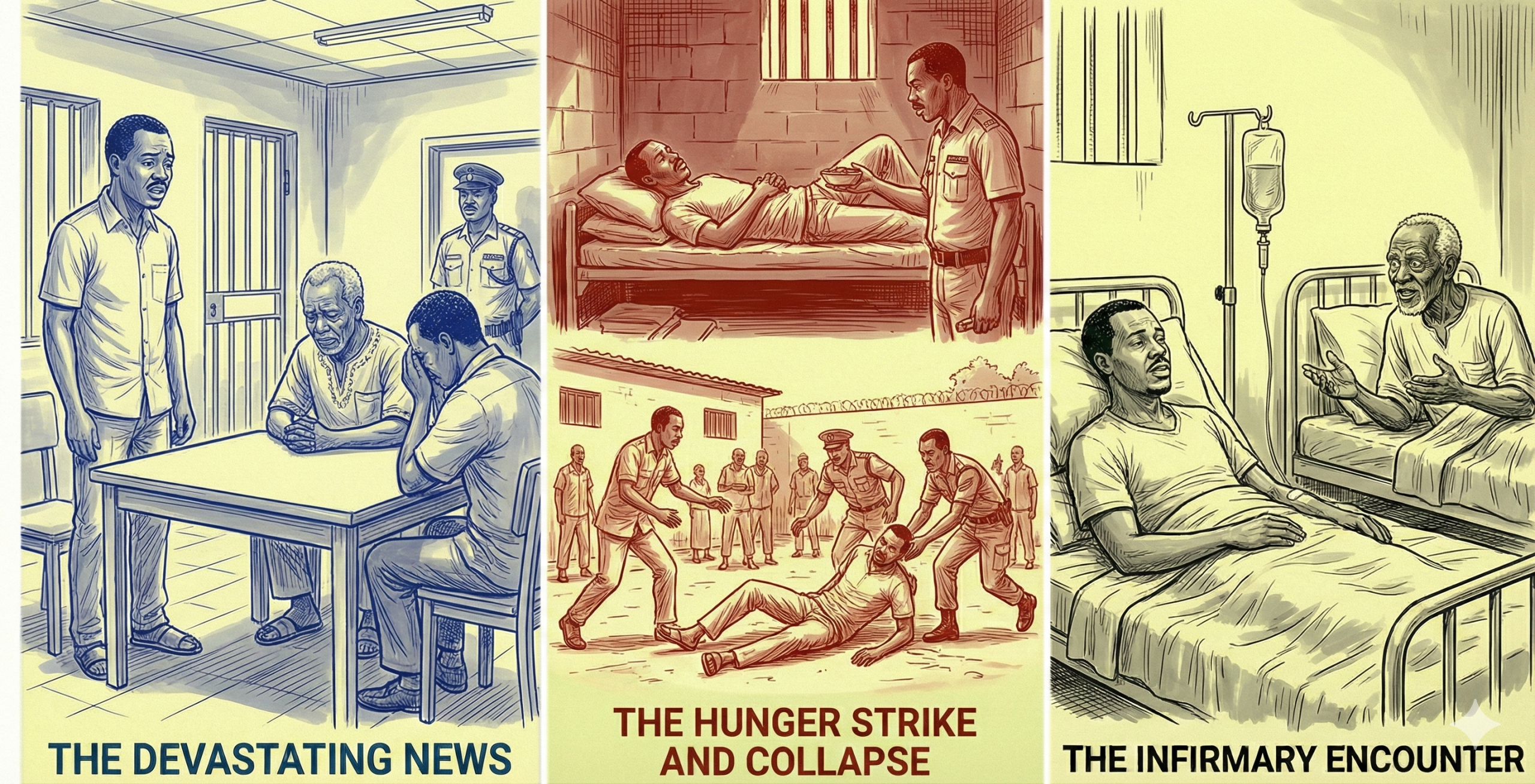

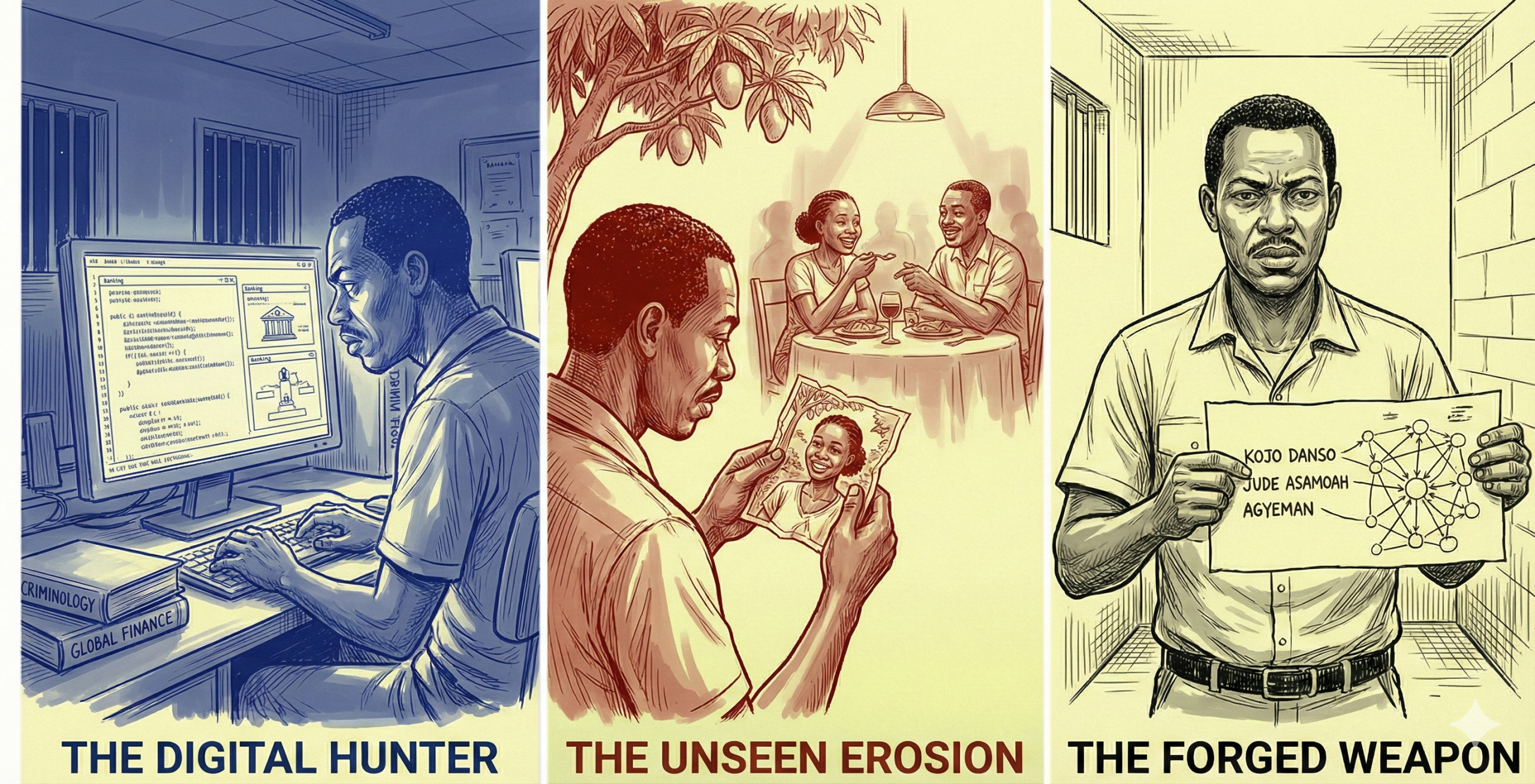

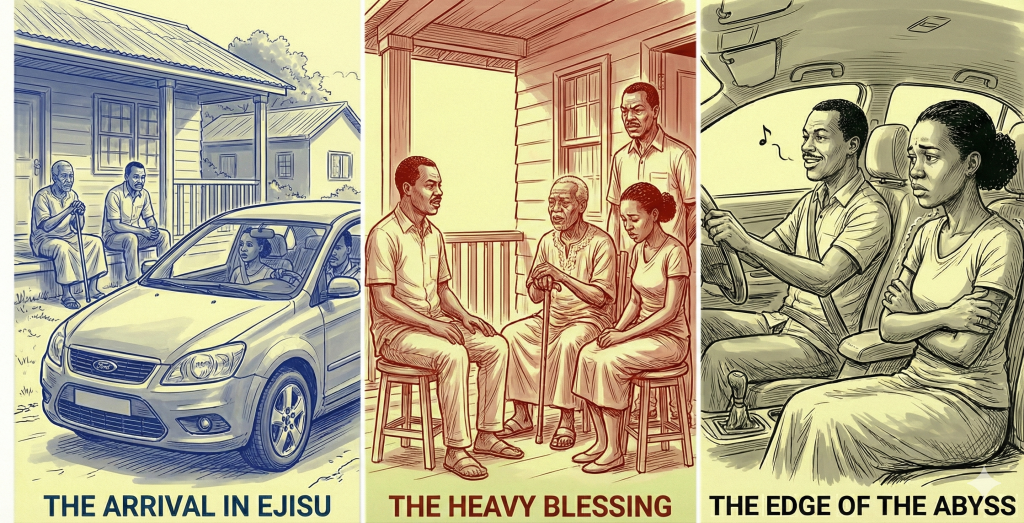

Three months later, the preparations for the union were no longer whispers; they were a mechanical inevitability. Osei’s Ford navigated the familiar potholes of the Kumasi-Ejisu road with a practised ease. Beside him, Abena sat in a silence so profound it seemed to occupy the entire cabin. She watched the green blur of plantain farms and cocoa trees, her mind a static hum of anticipation and dread.

They were heading to Ejisu to perform the hardest task since their engagement.

Uncle Gyasi’s house was a place of quiet dignity, where the air usually smelled of woodsmoke and damp earth. But as the silver car pulled up, the atmosphere felt charged with a sudden, sharp grief. Opanyin Dankwa was seated on the porch, his left hand resting on a walking stick. He had grown stronger in the years since the stroke, but the light in his eyes had become a wary, flickering thing.

“Papa,” Abena said, her voice barely a breath as she stepped onto the porch.

Opanyin Dankwa looked at her, then at Osei, who followed with a respectful but confident stride. The old man’s gaze lingered on the matching fabrics they were wearing, a subtle hint of the upcoming ceremony. He didn’t need to hear the words to know why they were there.

“Sit,” Gyasi said, appearing from the doorway. His face was a mask of sombre resignation.

Osei took the lead, his voice smooth and rehearsed. He spoke of the five years of waiting, of Abena’s loneliness in Tema, and of his own unwavering support. How the Oforis highly regard the Dankwa family, and he, Osei, was a Dankwa. Abena was not leaving; she was staying within the Dankwa family. He didn’t mention Kwesi’s name once, referring instead to “the circumstances” and “the long road ahead.”

“We have come to ask for your blessing, Opanyin,” Osei concluded, lowering his head. “Not as a stranger, but as a son who has been standing in the gap.”

The silence that followed was broken only by the chirping of insects in the yard. Opanyin Dankwa looked at Abena, his eyes searching hers for the girl who had promised to wait forever. He saw the exhaustion, the guilt, and the desperate need for a life that wasn’t a vigil.

“You have been a daughter to me, Abena,” Opanyin said finally, his voice a dry, rattling whisper. “My son is in a cage. The law has stolen his voice and his body. I cannot ask you to be buried in that cage with him. If the world has moved on, and you must move with it… Then we cannot hold your hand back.”

Uncle Gyasi nodded slowly, though his jaw was set tight. “We are family, Osei. If you have chosen to take this path, you must walk it with honour. We give you our blessing, however heavy it may be.”

The “blessing” felt more like a sentence.

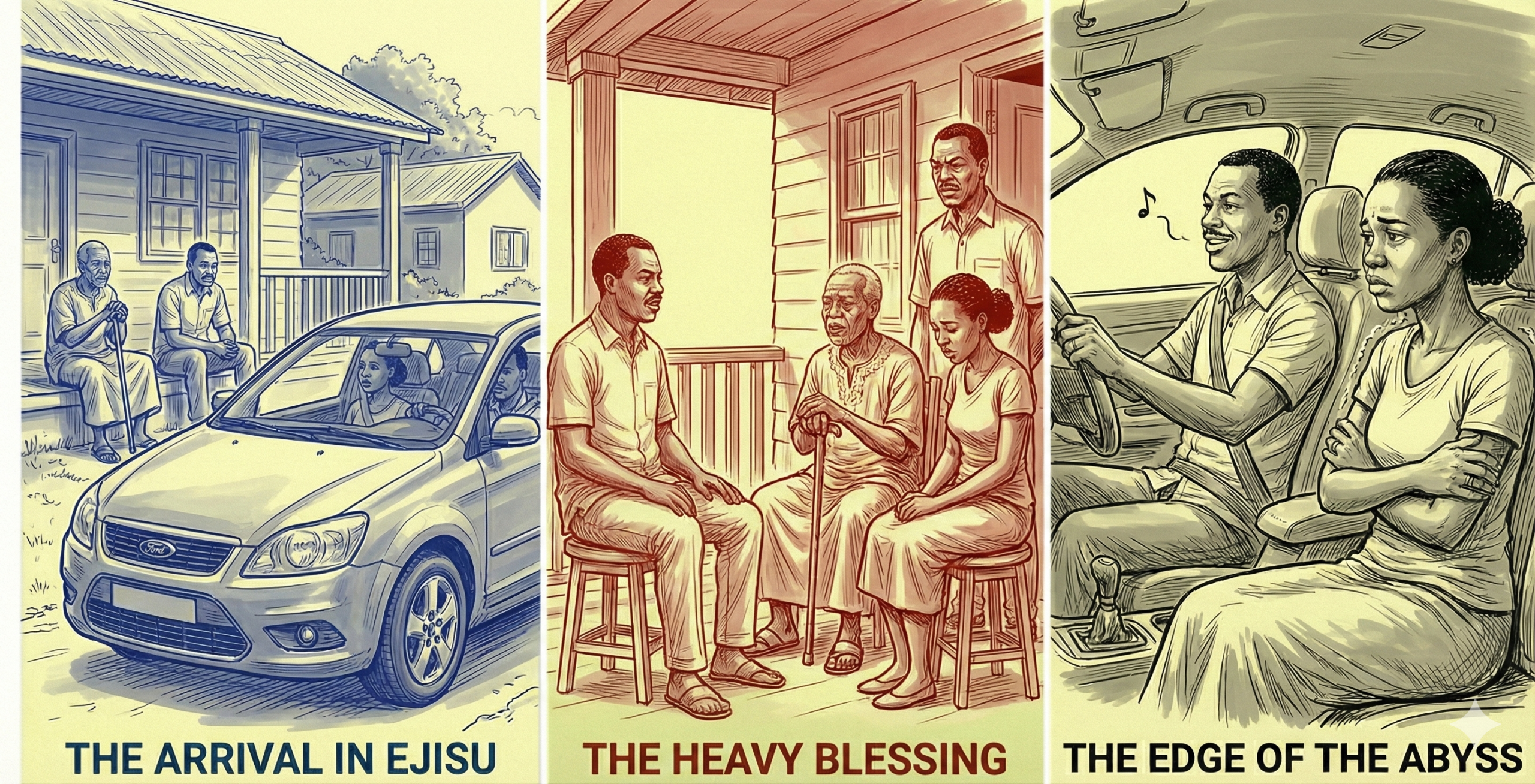

“But,” Opanyin added, his hand tightening on his stick. “Kwesi must hear this from us. Not from strangers. Gyasi and I will go to the prison tomorrow. We will tell him together.”

Abena felt a wave of nausea. The thought of looking at Kwesi through and telling him she was marrying his cousin, the man he trusted to protect her, felt like a physical blow.

“I’ll go with you,” Osei offered quickly.

“No,” Gyasi said, his eyes flashing with a sudden, rare sharpness.” Osei. Stay with Abena in Patasi.”

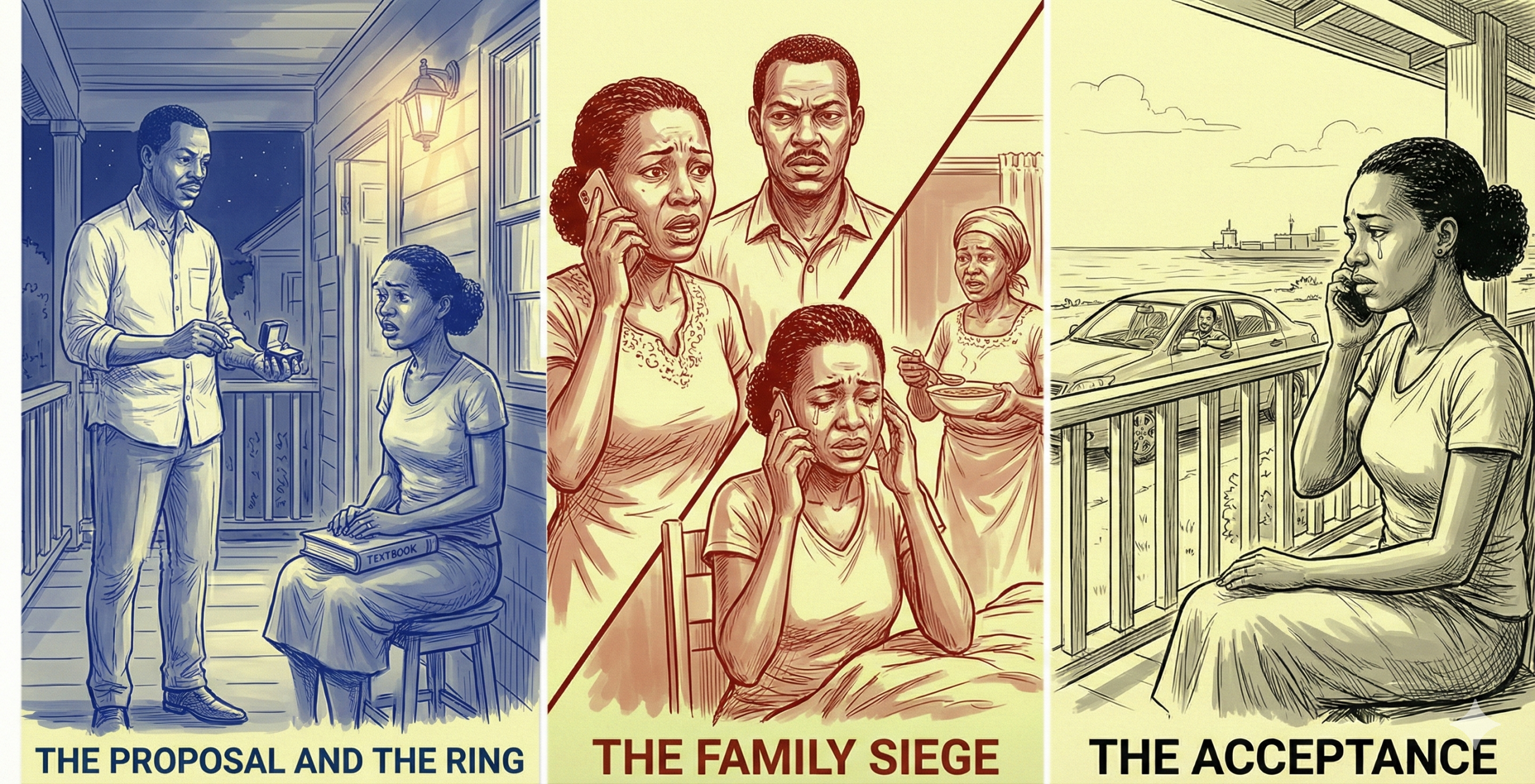

As they drove to Kumasi later that afternoon, Osei was whistling a low tune, a man who had cleared the final hurdle. In the passenger seat, Abena hugged herself, shivering in the heat. She had the blessing of the Dankwas, the approval of the Oforis, and a ring on her finger. She had everything she had convinced herself she needed to be happy, yet she felt as though she were standing on the edge of a great, dark abyss, waiting for the first step into the void.