By the middle of the fifth year, the “Long Wait” had reached a point of brittle exhaustion. In Kumasi, the harmattan dust of several seasons had coated the memories of the “Golden Boy” in a layer of grey indifference. But for Osei, the passage of time was a currency he spent with meticulous care. He chose a bright Tuesday in Patasi to make his formal opening.

He arrived at the Ofori residence looking every bit the successful Tema professional. He wore a crisp, tailored linen shirt, and his silver Ford was parked prominently at the gate. He carried a hamper filled with expensive wines, fine crackers, and specialised tea for Mr. Ofori’s digestion. He didn’t come as a suitor; he came as a “son of the house” returning with the spoils of his hard work.

“Osei, you shouldn’t have,” Mrs. Ofori said, her eyes brightening as she unpacked the hamper. “You are always looking after us.”

“It is my duty, Maa,” Osei replied, bowing his head respectfully. He sat across from Mr. Ofori, who was watching him with a mixture of appraisal and deep-seated relief.

The conversation drifted through the usual pleasantries until Osei leaned forward, his expression shifting into a mask of solemn concern. “I sat with Abena last weekend in Tema. She is tired, Papa. The work at the hospital is draining her, but it is the loneliness that is the real weight.”

Mr. Ofori sighed, the sound heavy with the guilt he had carried for five years. “We know, Osei. Every time she comes home, she looks like a shadow of the girl who used to sing in this kitchen.”

“She is thirty,” Osei said, the number landing like a gavel in the room. “The Ministry has finally paid her, she has her specialisation, and she has a good name. But she is waiting for a man who is legally dead to the world. Kwesi has fifteen years left. If she waits for him, she is waiting for the end of her own life.”

He paused, letting the silence do the work. Then, he spoke with a carefully practised humility. “I have come to love over the past three years. I have stood by her while others whispered. I want to give her a home, Papa. I want to give her the children she deserves while she is still young enough to hold them. I want to ask for your blessing to propose to her.”

Mrs. Ofori let out a small gasp, her hand flying to her chest. Mr. Ofori looked at the wine on the table, then at the man who had been the only constant support for his daughter. The “Kwesi Dankwa stain” had been a burden on the Ofori reputation for half a decade. Osei represented a clean break, a return to dignity.

“You have our blessing, Osei,” Mr. Ofori stated, his voice firming with a new sense of purpose. “You have been more of a husband to her in these five years than the law will ever allow Kwesi to be. Go to her. Tell her we are ready to open the door.”

Osei returned to Tema that evening, the engine of his Ford humming a song of triumph. He didn’t wait. He went straight to Community 4.

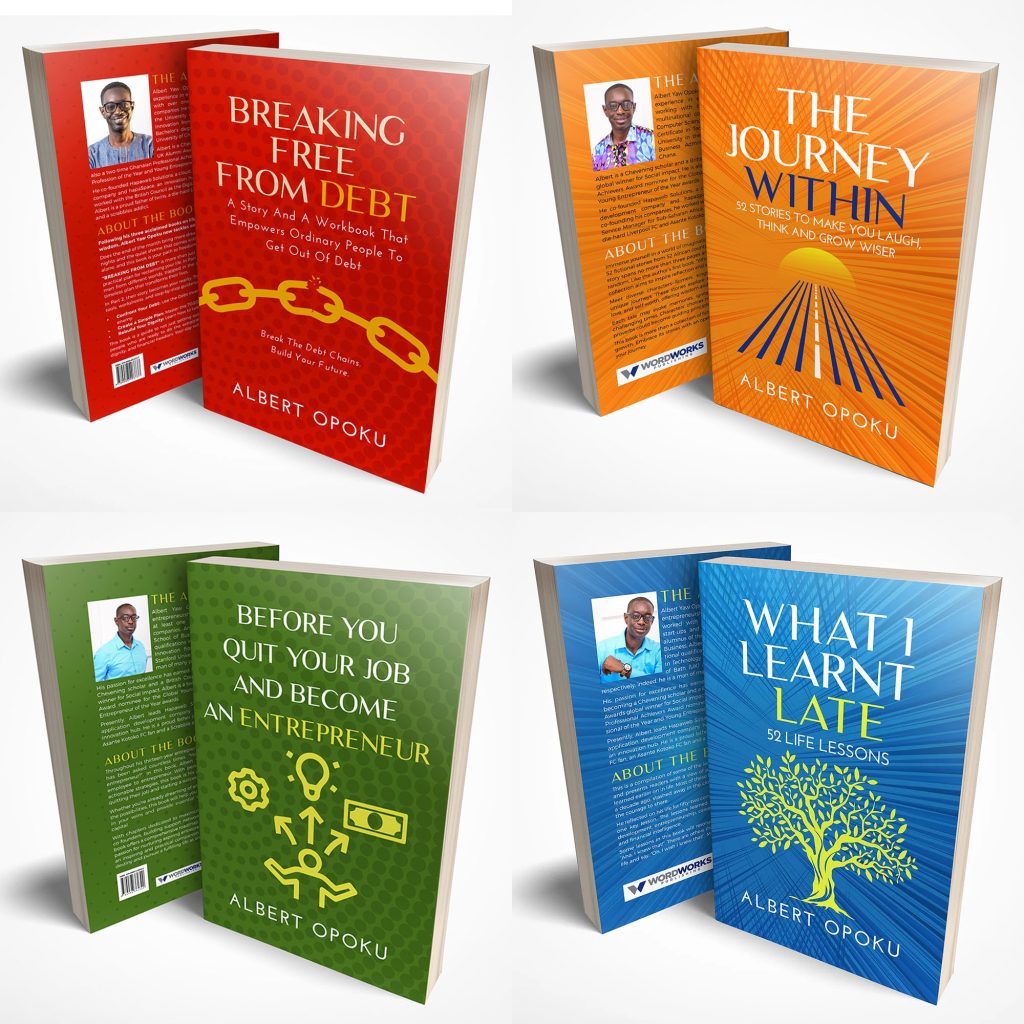

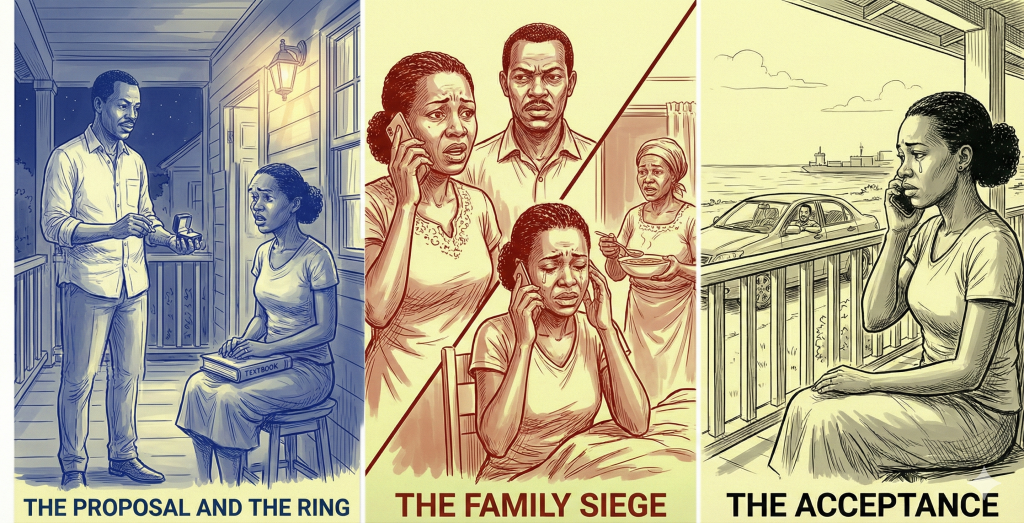

Abena was sitting on her small porch, a textbook on neonatal care open in her lap. The evening was humid, the salt-air sticking to her skin. She looked up as the Ford pulled into the driveway, a small, tired smile touching her lips.

“Osei? You’re back early,” she said.

He didn’t answer immediately. He walked up the steps, took the book from her lap, and set it on the small table. Then, he reached into his pocket and produced a small velvet box. He didn’t kneel; he knew Abena well enough to know that a grand spectacle would make her retreat. He simply stood before her, the ring catching the amber glow of the porch light.

“I went to Patasi today,” Osei said softly. “I spoke with your parents. I want this, Abena. And your parents agree.”

Abena went perfectly still. Her heart hammered against her ribs, not with joy, but with a sudden, suffocating panic. She looked at the ring, then at the man who had paid her rent, brought her food, and driven her to the prison for four years.

“Osei… I… I don’t know what to say,” she whispered, her voice trembling. “Kwesi—”

“Kwesi is the past,” Osei interrupted, his voice steady. “I am the one standing here. I am the one who will be here when you wake up and when you go to sleep. Don’t think about the debt or the years. Think about the life you want to live.”

“I need time,” Abena gasped, standing up and backing away from the box. “I need to think. It’s too much, Osei.”

“Take the time,” Osei said, his smile remaining patient, even kind. “I’m not going anywhere.”

But as he walked back to his car, Osei pulled out his phone. He didn’t give her time to think. Before he even reached the end of the street, he had dialled Mrs. Ofori’s number.

“Maa,” he said into the phone, his tone urgent. “I’ve asked her. She is scared. She is holding onto the past. She needs to hear from you. She needs to know that the family is waiting for her to come home.”

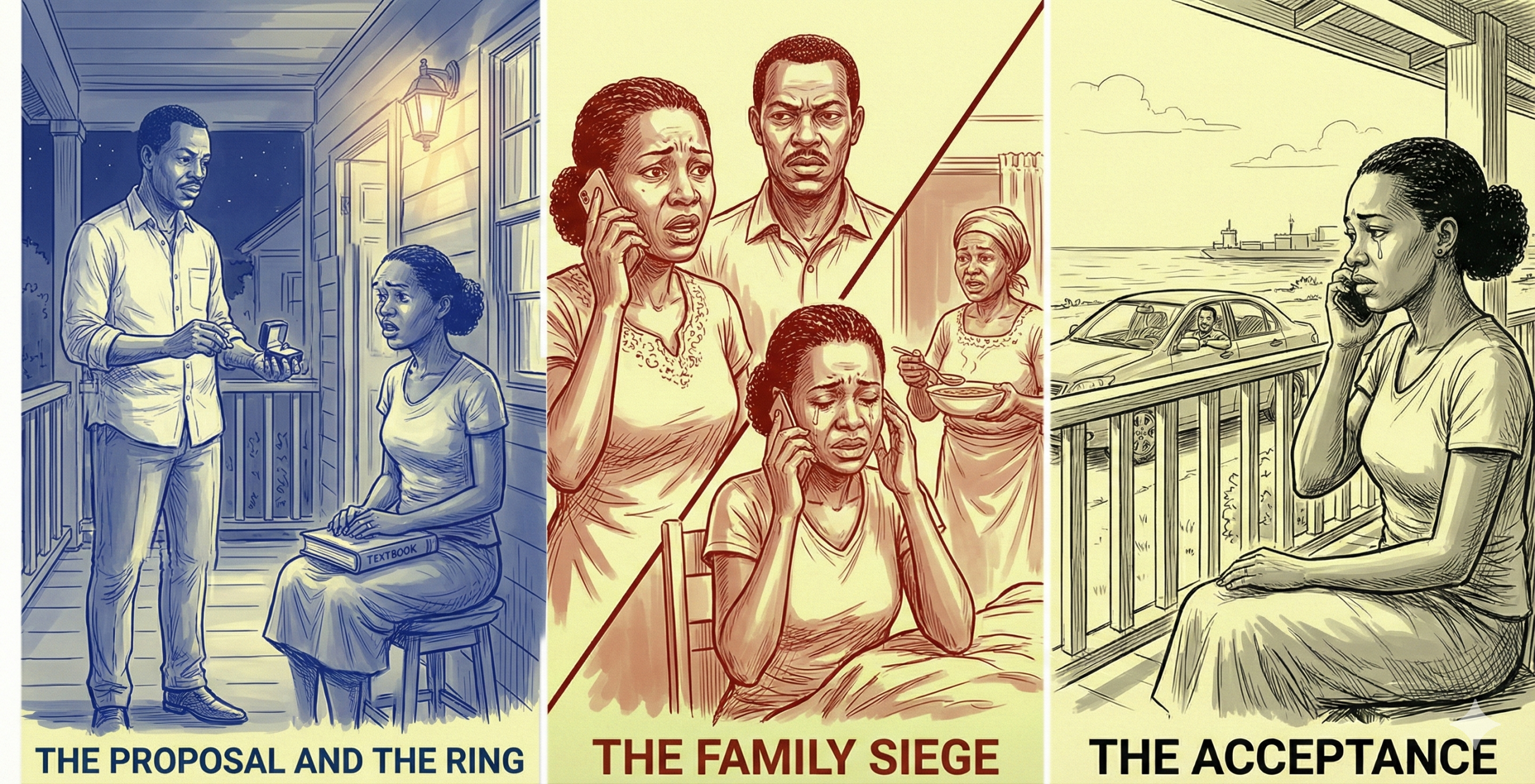

The “siege” had officially begun.

The calls started the next morning, before Abena had even left for her shift.

“Abena, my child,” her mother’s voice came through the handset, thick with unshed tears. “Osei told us. He is such a good man, and his heart is so heavy. Why are you punishing yourself? Why are you punishing us?”

“I’m not punishing anyone, Maa,” Abena said, gripping the edge of the sink. “I just… It’s only been five years. I promised him.”

“Five years is a lifetime!” her mother cried. “In five years, children have started school. In five years, your father’s hair will have turned white. He doesn’t say it, but he wakes up at night wondering if he will ever hold a grandchild from his only daughter. Do you want his last memories of you to be these lonely visits to a prison yard?”

Every evening followed the same pattern. If it wasn’t her mother, it was her father, his voice stern and weary, reminding her of the “dignity” Osei offered. Even the social silence of Tema seemed to conspire against her. At the hospital, she watched young couples bringing in their newborns, their faces lit with a future she had put on indefinite hold.

The final blow came from an unexpected quarter. Maame Efua, her landlady who had taken Abena as her own daughter, was usually a woman of few words. On a rainy Friday evening, she knocked on Abena’s door. She carried a bowl of hot light soup.

“Eat, my daughter,” the widow said, sitting on the edge of Abena’s bed. “You are fading away.”

“I’m just tired, Maame,” Abena replied, the steam from the soup dampening her face.

“You are tired because you are carrying a dead man on your back,” Maame Efua said plainly. “I have lived a long time, Abena. I have seen women wait for men who went to sea, and men who went to war. The ones who survived are the ones who knew when to come in from the rain. Osei is a good roof. He is sturdy. He is here. Kwesi… Kwesi is a memory that is eating your youth.”

Abena looked at the widow, seeing the reflection of her own possible future in the older woman’s solitary life. She did the math again, the numbers swirling in her mind like a fever dream. Thirty years old. Fifteen more years. Forty-five.

The image of her forty-five-year-old self-standing at the ACP gates felt like a haunting. She would be a woman who had spent her prime in a bus seat and a visitor’s booth. She would have a career, yes, but her home would be empty.

She thought of Osei. He was successful. He was kind. He was her cousin, but more than that, he was her present. He knew her favourite food, the way she liked her tea, and the specific exhaustion of a night shift. He didn’t live in a cell; he lived in a world where they could walk on the beach at night and plan for a nursery.

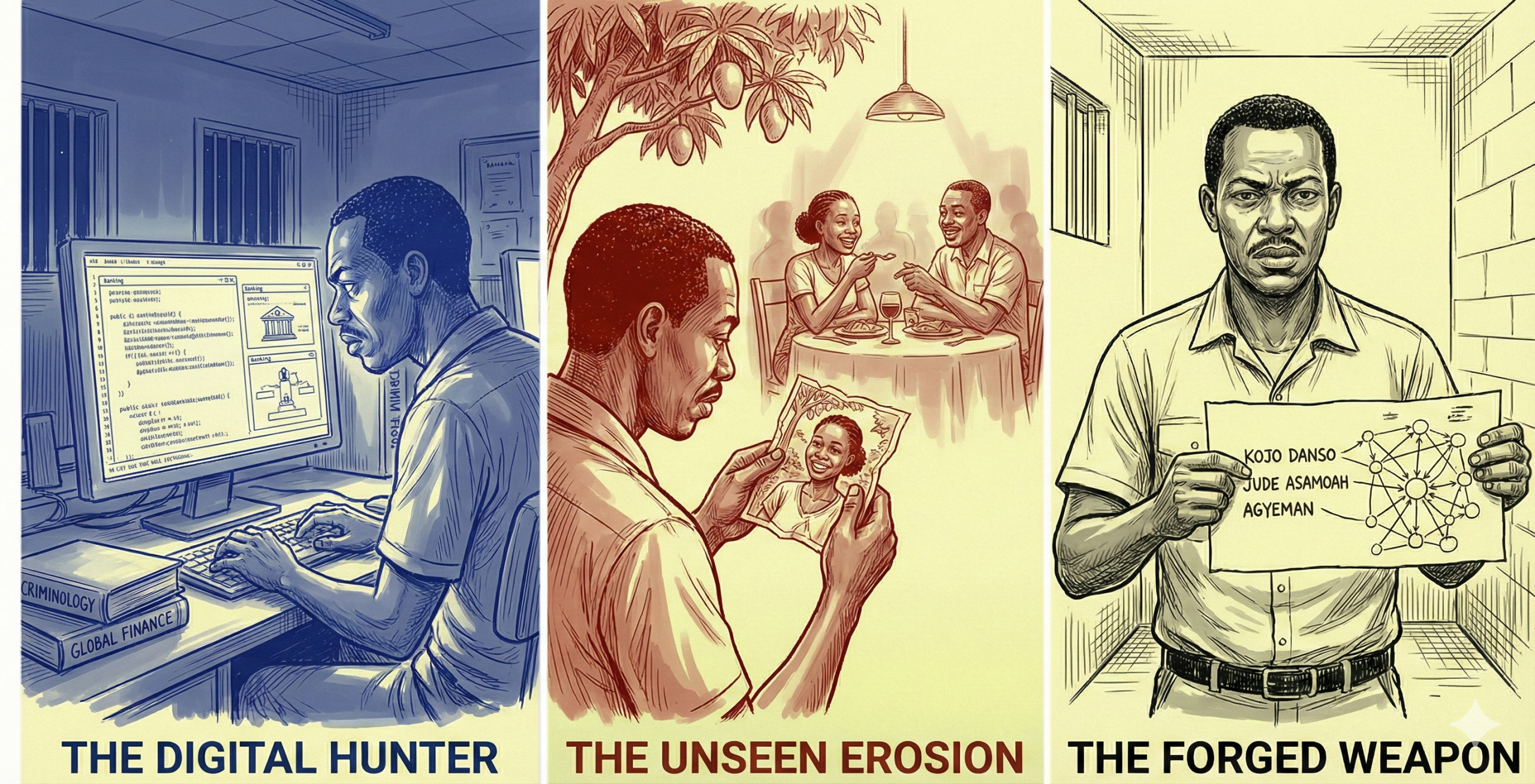

On Saturday morning, Abena didn’t pick up her textbooks. She sat on her porch for a long time, watching the salt-mist rise from the harbour. Then, she picked up her phone and dialled Osei’s number.

“Osei?” she whispered when he answered on the first ring.

“I’m here, Abena.”

“Come… come to the house,” she said, her voice breaking. “I’m ready. I’ll do it. I’ll marry you.”

The preparations began with a speed that felt like a whirlwind. Osei was a man of action when he had a prize in sight. Within forty-eight hours, the Oforis were notified, and the “Kwesi Dankwa shadow” began to be scrubbed from the family’s public narrative. Mrs. Ofori began coordinating with kente weavers in Bonwire, her voice full of a joy that had been absent for five years.

For Abena, the acceptance brought a strange, numb peace. The “siege” was over. The questions from her peers would stop. The pity would turn into congratulations. She told herself she was being practical. She told herself she was being a good daughter. But deep in the quiet of the night, when the salt air grew cold, a small part of her heart still felt like it was being buried alive. She was moving forward, but she knew that the road ahead was built on the wreckage of the man she had truly loved.