In the quiet village of Ejisu, the afternoon sun filtered through the broad leaves of the plantain trees in Uncle Gyasi’s backyard. Opanyin Dankwa sat on the porch, his recovery nearly complete. He could move his limbs, his speech was clear, and the physical fog of the stroke had lifted. But a different kind of fog remained, the one Gyasi had carefully maintained for over a year and a half.

“Gyasi,” Opanyin said, his voice firm. “The ‘long trip’ has lasted too long. Kwesi’s phone is still off. Mr. Mensah sends money, but no letters. I am a father, not a child. Tell me the truth.”

Gyasi looked at his brother, seeing the old fire returning to the patriarch’s eyes. He knew he couldn’t hold the lie any longer. With a heavy heart, Gyasi sat beside him and told him everything, the events after the “Knocking” ceremony arrest, the trial, Jude Asamoah’s betrayal, and the twenty-year sentence at the Ashanti Central Prison.

Opanyin Dankwa didn’t scream. He didn’t collapse. He simply bowed his head, and for a long time, the only sound was the rustle of the wind. Then, the tears came, thick, silent tracks down his weathered cheeks. He wept for the stolen years, for the kente cloth turned into a prison tunic, and for the son who had sacrificed his freedom to save his father’s life.

After an hour, he wiped his eyes with the edge of his cloth and stood up. “Take me to him,” he said, his voice steel. “Take me to my son.”

“Opanyin, it is a hard place,” Gyasi warned. “The sight of him behind bars… it might be too much.”

“No,” Opanyin replied. “The sight of him will give me life. And when we get there, Gyasi, we will not cry. We will tell him to hold onto hope. We will tell him that the Dankwa blood does not dry up in the sun.”

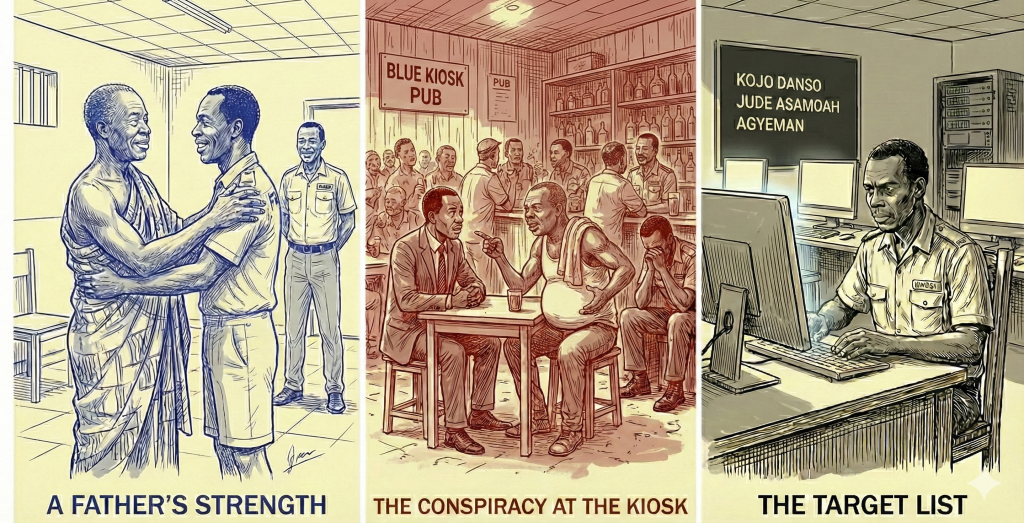

The visit at the ACP was unlike any other. When Kwesi was led into the visitation room and saw his father standing there and not in a hospital bed, but upright and strong, he felt a surge of joy so profound it nearly brought him to his knees. They hugged for what felt like eternity.

“I am well, Kwesi,” Opanyin said. “But you, you must keep your head high. You are learning things here that they cannot lock up. Use this time. Become a giant in this small room, so that when the gates open, they will be too small for you.”

Seeing his father’s resilience gave Kwesi a new, cold-blooded motivation. That night, back in the lab, he didn’t just open his coding environment. He enrolled in an intensive, distance-learning course in Global Banking and Finance.

“If I want to dismantle them,” he whispered to the glowing screen, “I have to understand the temple they worship in.”

He began to study the architecture of the banking institution, how international transfers were routed, the protocols of the SWIFT system, and the intricacies of chartered banking. He wasn’t just learning to be a programmer; he was training to become a forensic shadow. While Kojo Danso was busy amassing wealth in Kumasi, buying up property and flashy cars, Kwesi was learning exactly how to find where every single pesewa was hidden. The “Institutional Wall” was still high, but Kwesi was no longer looking for a door; he was learning how to take apart the foundation.

While Kwesi was dissecting the architecture of global finance, Kojo Danso was enjoying the spoils of its local equivalent. As the second year of his directorship drew to a close, Kojo had transformed from a nervous accountant into a man of immense, unearned wealth. With Asamoah Snr retired and out of the way, Kojo was his own boss. He had bought a sprawling villa in the upscale hills of Ahodwo and replaced his modest sedan with a silver Land Cruiser.

But wealth built on betrayal has a way of attracting parasites.

At the Blue Kiosk in Kejetia, the afternoon rush was in full swing. The air was thick with the scent of roasted meat and the rhythmic thumping of highlife music. Agyeman sat at a corner table, his face darkened by years of simmering resentment. Over his shoulder was his trademark thin, half-towel, stained with the dust of the market and the sweat of a man who felt the world owed him more than he had received.

“You are late, Kojo,” Agyeman grumbled as Kojo slid into the plastic chair opposite him, looking entirely out of place in his expensive Italian suit.

“I am a Director now, Agyeman. I have meetings,” Kojo snapped, looking around the pub with visible distaste. “What is so urgent that it couldn’t wait for a phone call?”

“I want my payback,” Agyeman said, leaning forward. He wiped his forehead with the half-towel, then draped it back over his shoulder. “I am trying to bring in two containers of rice from Thailand. The customs officers at the port are breathing down my neck. I need licenses, and I need you to use your ‘logistics’ contacts in Tema to clear the path.”

Kojo let out a sharp, mocking laugh. “You want my help with imports? My company is Ashanti Cocoa. We export. We don’t import, sorry, Agyeman. I can’t help you.”

Agyeman’s eyes flared with a sudden, dangerous heat. He slammed his fist on the table, rattling the beer bottles. “You can’t help me? After everything I did? Who told you about the family debt? Who helped you draft that letter? You are sitting in that big office and driving that silver car because of the trap I helped set!”

Kojo’s face went from pale to ash-grey. He looked around frantically, but the noise of the pub seemed to offer a thin veil of safety. “Keep your voice down!” he hissed.

“I will not!” Agyeman shouted, standing up. The half-towel slipped slightly but stayed anchored. “You think you can just discard me? I was the key to Kwesi Dankwa’s conviction! If I don’t get those containers, Kojo, I will make sure everyone knows exactly how the ‘Golden Boy’ was buried.”

Kojo felt a cold sweat prickling his neck. Agyeman was a loose cannon, and a desperate shopkeeper with nothing to lose was more dangerous than any prosecutor. He realised, with a sinking feeling, that the “debt” he owed Agyeman would never be fully paid.

“Fine,” Kojo whispered, his voice trembling. “Sit down. I will handle it. I will make a few calls”

Kojo stepped outside and pulled out his phone, his hands shaking as he dialled a number he hadn’t called in months. Asamoah Snr answered on the third ring, his voice sounding raspier than usual in retirement. Kojo explained the situation in frantic, hushed tones.

“He’s threatening us, sir. Agyeman. He wants his containers cleared at the port or he’ll talk.”

There was a long silence on the other end. “He is a small man with a big mouth, Kojo,” Asamoah Snr finally said, his tone icy. “But small men can cause large headaches. Tell him it is done. I will call the port. Charles will handle the customs issues for him personally. Tell him to stay quiet and stay in his shop.”

Kojo returned to the table, the colour slowly returning to his face. “It’s settled. Charles will handle everything at the port for you. Your containers will pass. Now, for the last time, leave me alone.”

Agyeman smiled, a slow, yellow-toothed grin. He adjusted the towel on his shoulder. “That is all I wanted, Director.”

Across the pub, tucked into a dark corner, Officer Owusu sat with a glass of gin. He had been looking for a power outlet for his dead phone and had been crouched near the wall, right behind their table. He had frozen when he heard a familiar name: Kwesi Dankwa. He stayed perfectly still, listening as the two men argued.

The next morning, Owusu stood outside the computer lab at the ACP. When Kwesi looked up, he saw the officer’s face was grave.

“I was at the Blue Kiosk yesterday, 4405,” Owusu said, closing the door. “I heard two men arguing. One was a big man in a suit, the other had a thin towel draped over his shoulder. I didn’t know them when I sat down, but I didn’t need a formal introduction to know who they were by the time they finished.”

Owusu leaned over the desk. “The shopkeeper was calling the big man ‘Kojo’ and ‘Director.’ He was furious, shouting about a debt and a letter he helped draft to set a ‘trap’ for you. And the big man… he called the other one ‘Agyeman.’ He told him he’d get someone named Charles to clear some containers at the port to keep him quiet.”

Owusu’s voice was a whisper. “He was the one who gave them the information on your father’s debt, Kwesi.”

Kwesi felt a cold hum of emerging fury. He hadn’t known for certain how Kojo had found out about the debt, but now the pieces fell together with sickening clarity. Agyeman. The neighbour who had smiled as he took the money.

“Thank you, Owusu,” Kwesi said, his voice a low, steady hum.

He turned back to the screen and opened a blank document. He typed Kojo Danso and Jude Asamoah at the top. Then, with a slow, deliberate keystroke, he added the third name: Agyeman. The second year of his sentence was almost over, and while he suspected there were others, the circle of the primary betrayers was coming into focus. He was no longer just a victim; he was a man with a target.