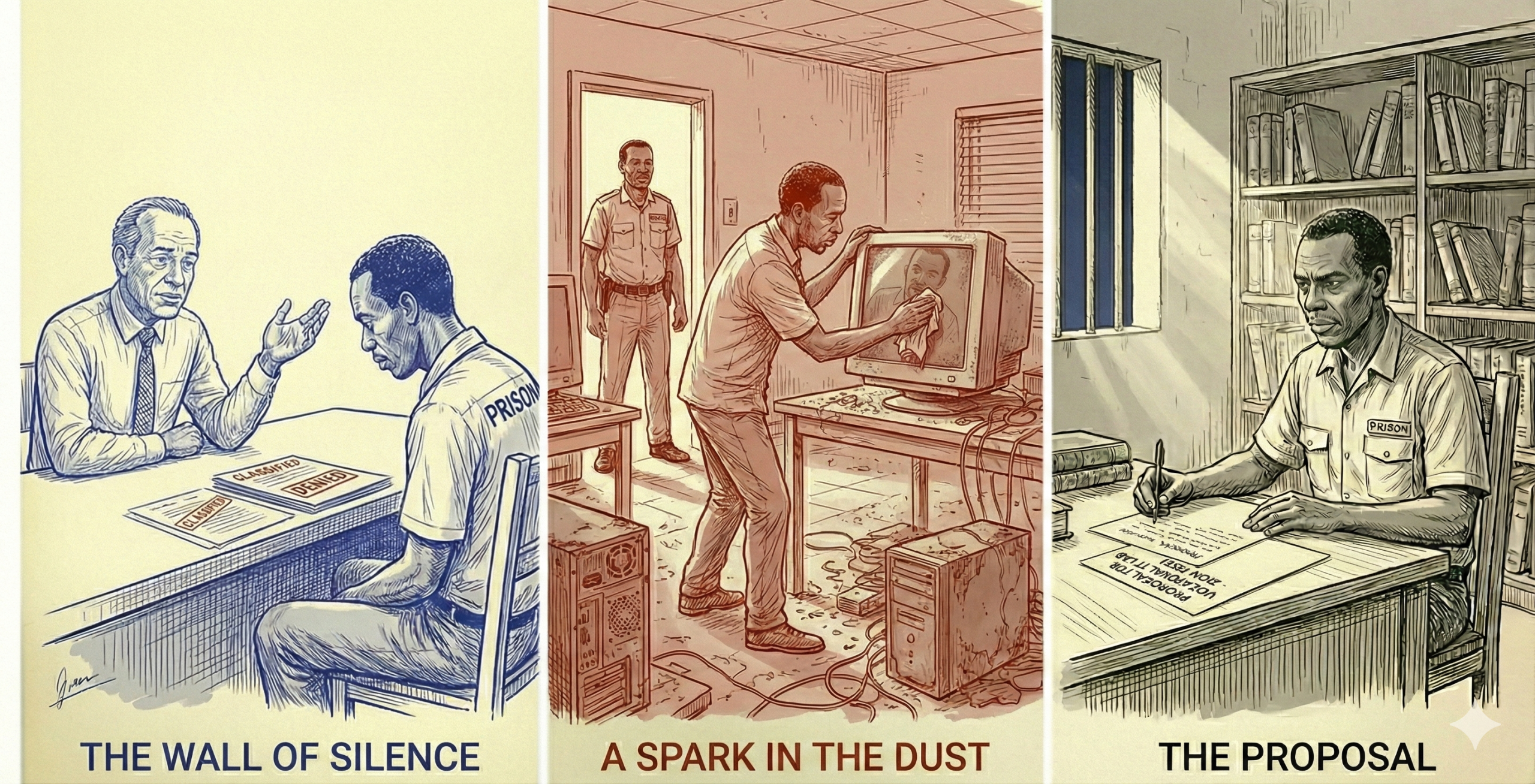

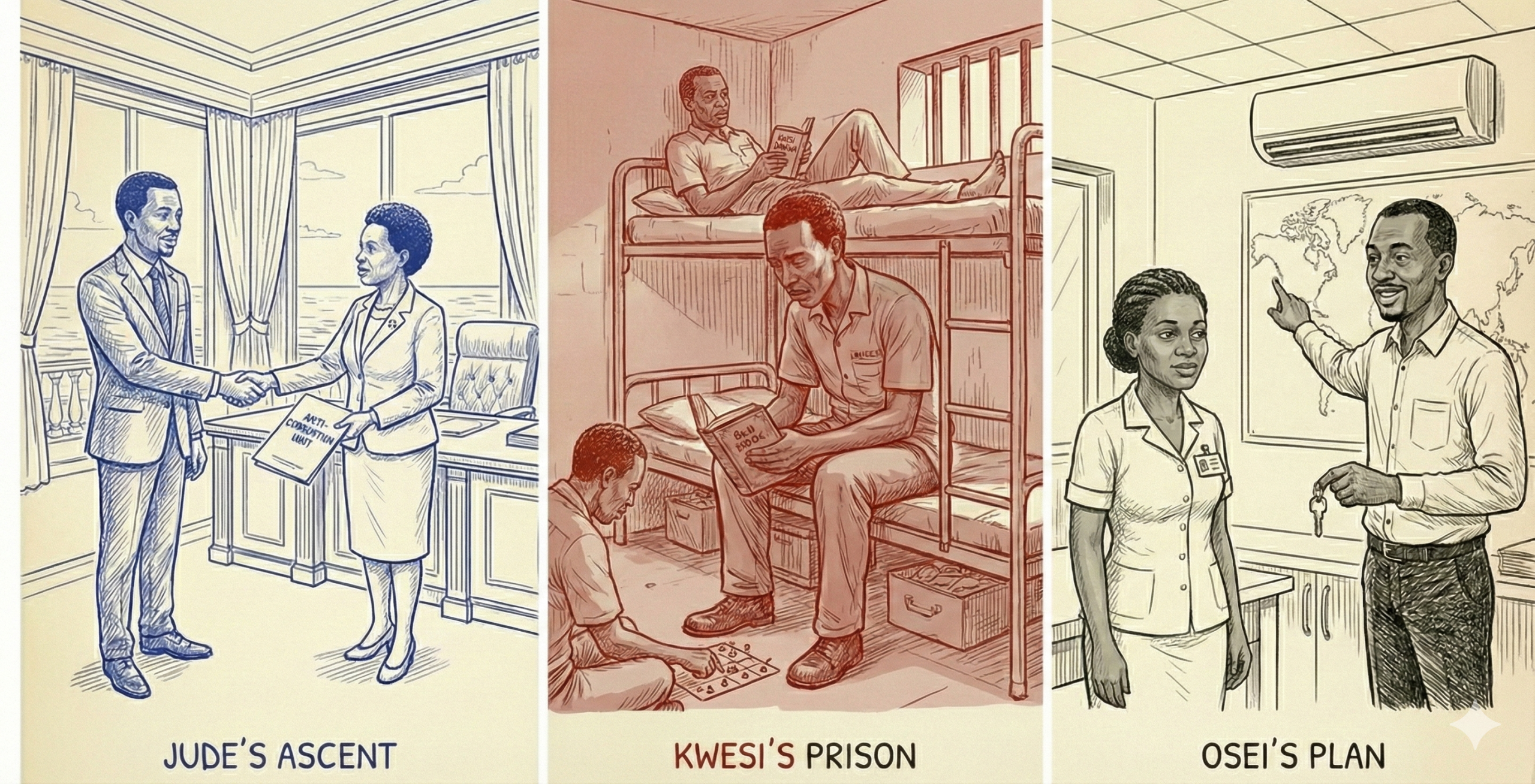

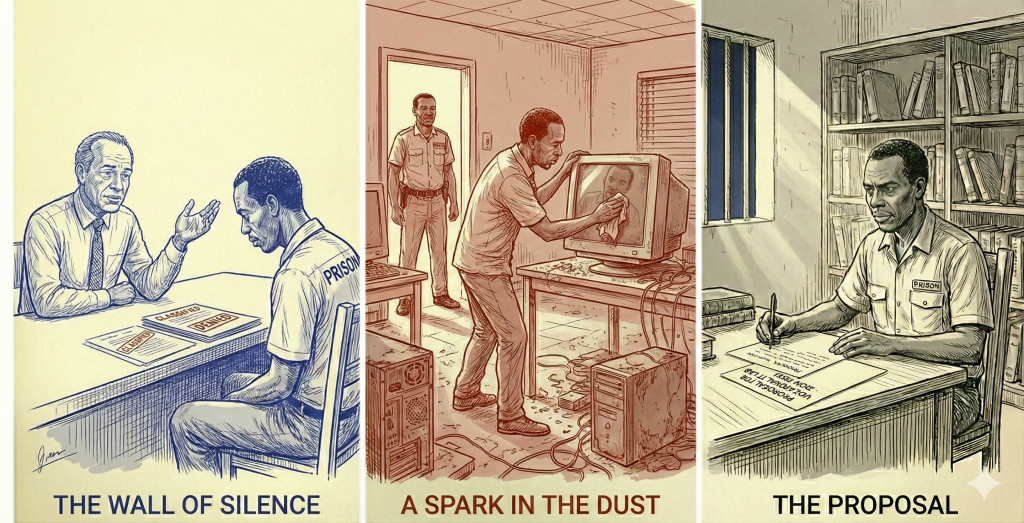

The following Monday, Lawyer Kwarteng made the familiar, soul-crushing trek to the Ashanti Central Prison. The smell of the place always seemed to cling to his suit long after he left. In the visitation room, Kwesi looked thinner than he had a month ago, his prison tunic hanging loosely over his collarbones, but his eyes were still sharp.

“I need the truth, Lawyer,” Kwesi said, his voice level despite the tremor in his hands. “Don’t tell me about hope today. Tell me about the facts.”

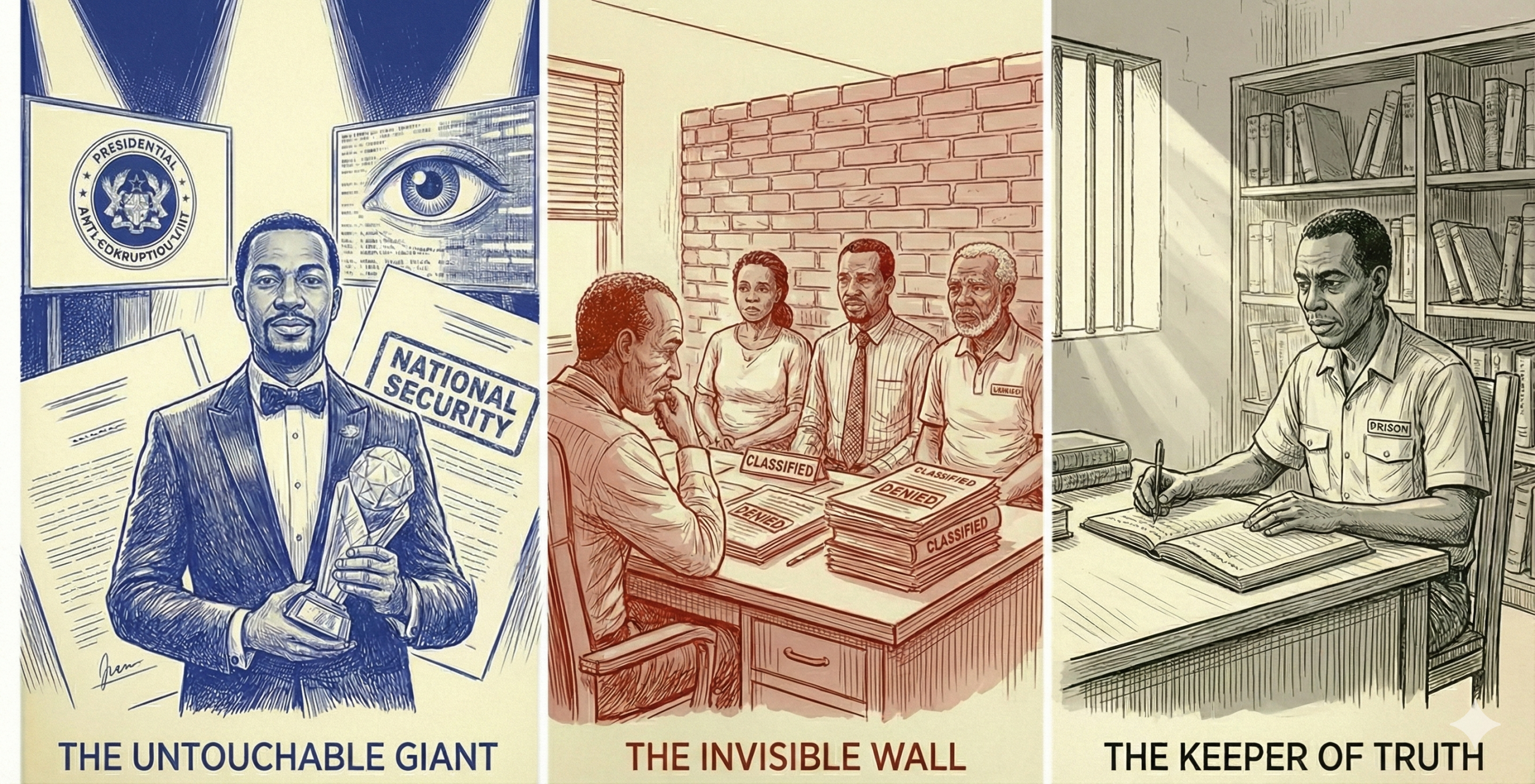

Kwarteng sighed. “The facts are hard, Kwesi. The investigation has hit a wall. Jude has used his position in the PACU to classify the logistics records. Legally, we are blocked. Every PI we hire finds the same thing: a door that only Jude Asamoah has the key to.”

Kwesi was silent. He looked past the lawyer, his gaze landing on a patch of sun hitting the concrete floor. “So, that’s it then. I stay here for nineteen more years while he receives awards in Accra.”

“We aren’t stopping,” Kwarteng insisted, though the words sounded hollow even to him. “But for now… we have to wait. The system is currently working for them, not us. You have to find a way to endure this, Kwesi. You have to survive the silence.”

When the visit ended, Kwesi walked back to his cell in a daze. The weight of the nineteen years felt like a physical pressure on his chest, a mountain of days he wasn’t sure he could climb. He sat on his bunk bed, his head in his hands, oblivious to the shouting of the inmates in the corridor. For the first time since the “Knocking,” the flicker of fire in his belly felt like it was finally going out.

Officer Owusu stood near the end of the block, watching 4405. He had seen this look far too many times, the ‘prison fog,’ the moment a man realises the gate isn’t opening anytime soon. Owusu had taken a liking to the quiet prisoner who spent his hours in the library, the one who didn’t join the gangs or engage in useless banter.

“You’re sinking, 4405,” Owusu said, appearing at the cell door.

Kwesi didn’t look up. “There’s nowhere else to go, Officer.”

“There is a room,” Owusu replied, jangling his keys. “The old computer lab in the administrative wing. It hasn’t been opened since the last NGO left five years ago. It’s full of dust, rusted towers, and dead monitors. The OIC (Officers-in-Charge) wants it cleared out or turned into a storage room for old uniforms.”

Kwesi finally looked up. “A computer lab?”

“He needs someone who won’t steal the copper wiring and knows how to make a list. I told him you were a logistics man. I told him you could handle the inventory.” Owusu leaned in, his voice a low rumble. “It’s quiet in there. And the machines… they don’t care about the law. They only care about logic.”

A few hours later, after a brief, disinterested nod from the OIC, Owusu led Kwesi to the far end of the block. The heavy iron door groaned as it was thrown back. The air inside was thick with the scent of ozone and ancient dust. Rows of beige CRT monitors sat like sightless eyes on rickety tables. Rusted CPU towers lay on their sides, their internal components exposed like skeletal remains. It was a graveyard of 90s technology, a room of forgotten silicon.

Kwesi stepped inside, his bare feet stirring the dust. He picked up a keyboard, blowing a thick layer of grey silt from the keys. It felt strange, a piece of the world he used to belong to, a tool of the life he had lost.

“Clean it up,” Owusu said, handing him a rag and a bucket of soapy water. “If you can make sense of this junk, maybe the OIC won’t turn it into a closet.”

Kwesi began to wipe down the first monitor. As the grime cleared, revealing the dark, reflective glass, he saw his own reflection—haggard, thin, but standing. He realised that here, among the broken circuits and the silent processors, he found a different kind of order. The law was a maze of lies, but a machine either worked or it didn’t. As he began to organise the rusted towers, the dejection that had threatened to swallow him began to recede, replaced by a cold, focused curiosity. He was the Librarian of Books, but in this room, he would become something else.

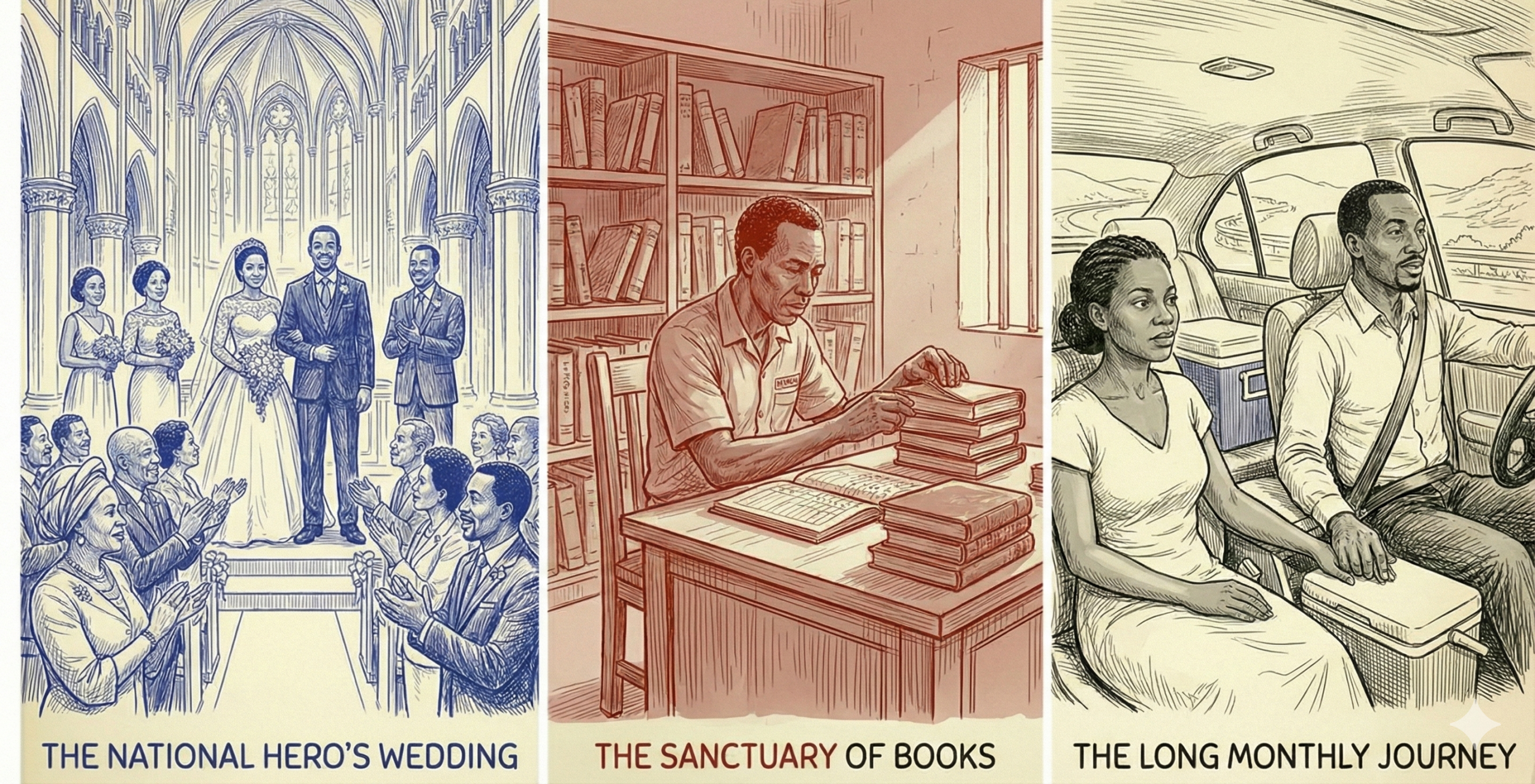

A year and a half into his sentence, the computer lab was no longer a graveyard. Kwesi had stripped the rusted machines to their frames, salvaging RAM sticks and power supply units from the least-damaged towers to resurrect four functioning systems. They were slow, wheezing relics running outdated operating systems, but when the first screen flickered to life with a pale blue glow, Kwesi felt a jolt of electricity in his own spirit.

However, he knew that four dying PCs weren’t enough. The OIC had been watching his progress with a sceptical eye, surprised that a prisoner could derive so much focus from scrap metal.

“You’ve done well with the junk, 4405,” the OIC said during an inspection, tapping his baton against a polished monitor. “But I need this room to be more than a hobby shop. I need results I can show the regional inspectors.”

“Then give me the authority to ask for help, sir,” Kwesi replied, standing at attention. “The private sector looks for Corporate Social Responsibility projects. If we can show them a plan for a real vocational lab, they might provide the equipment.”

The OIC laughed, a dry, grating sound. “You want to write letters to big firms? From a cell?”

“I was a logistics manager at the Ashanti Cocoa Buying Company, sir. I know how to write a proposal that speaks their language.”

To his surprise, the OIC agreed. For the next three weeks, Kwesi spent every evening in the library, hunched over A4 sheets as he wrote a proposal to several IT companies in Kumasi, including Zion-Tech, one of the leading IT infrastructure firms in Kumasi. He didn’t write as a beggar; he wrote as a strategist. He detailed the potential for vocational training to reduce recidivism, the tax benefits for the donor, and the positive PR of “bridging the digital divide” in the heart of the prison system.

Six weeks later, a white Toyota Hilux from Zion-Tech pulled through the prison gates.

The OIC was stunned as technicians unloaded ten modern workstations, a server rack, and a high-speed satellite link. The CEO of Zion-Tech had been so impressed by the professional, data-driven quality of the “Prisoner 4405 Proposal” that he had personally authorised the donation.

As the technicians installed the new gear, the lab was transformed. The smell of dust was replaced by the ozone-sweet scent of new electronics. Kwesi was no longer just the inventory man; he was the Lab Coordinator.

His real education began the night the internet was switched on.

While the other inmates slept, Kwesi sat in the glow of the new monitors. He didn’t search for news of his case or the social pages of Jude Asamoah. Instead, he searched for “Introduction to C++” and “SQL Database Management.” He discovered that the digital world was built on structured queries and logical commands, a world where every action had a trace and every secret was just a line of code waiting to be decrypted.

He started small, writing simple scripts to manage the prison’s library inventory, but soon he was spending hours on open-source coding forums. Under a pseudonym, he learned how to navigate the “Deep Web” and how forensic accounting software could be used to track offshore money.

One night, as he successfully compiled his first complex program, Kwesi looked at his hands. They were still the hands of a prisoner, but the mind behind them was expanding. Jude Asamoah had used the law to build a wall, but Kwesi was realising that the world’s most powerful walls were no longer made of stone; they were made of data. And data, he was learning, could be hacked.