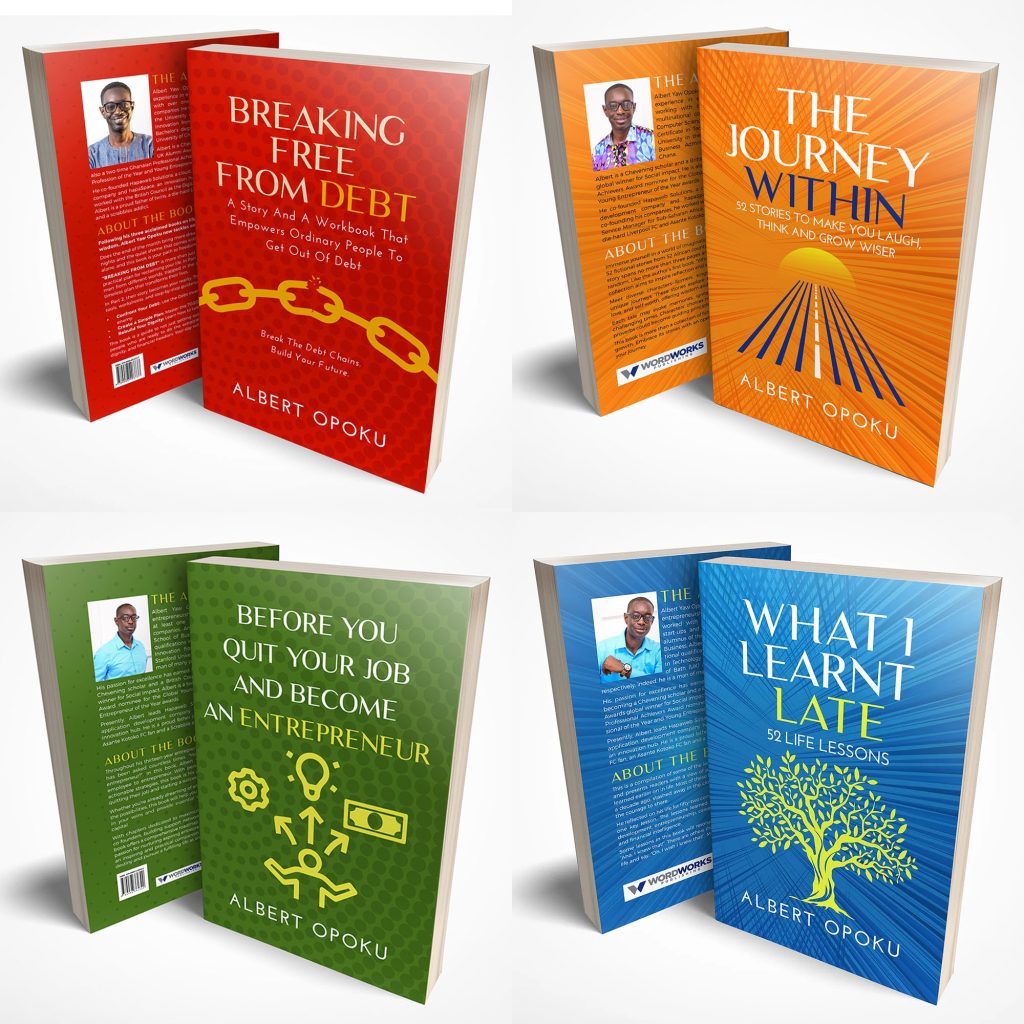

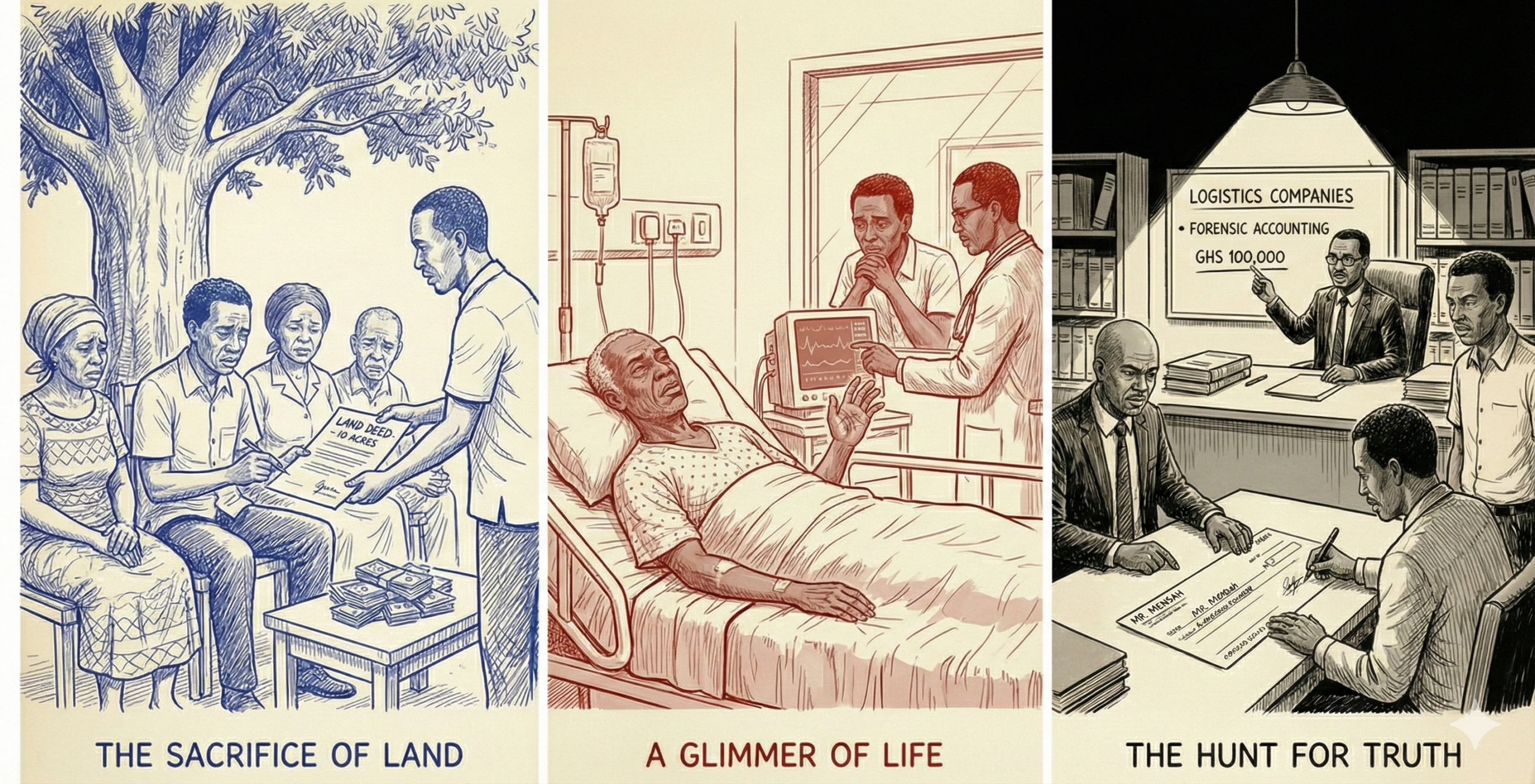

By the end of the third month, Jude Asamoah had reached a height that most lawyers spent forty years chasing. In a glittering ballroom at the Ambassador Hotel in Accra, he stood under a barrage of camera flashes, clutching a heavy crystal trophy. He had just been named the “Best Criminal Lawyer in West Africa” for his unwavering commitment to the rule of law and his unprecedented success in dismantling smuggling networks.

He was the postal boy of the legal profession—uncompromising, brilliant, and clean. From his new headquarters at the Presidential Anti-Corruption Unit (PACU), Jude operated with a budget and an authority that made even the Chief of Police nervous. He had the best surveillance equipment, the most loyal investigators, and a direct line to the President.

But Jude’s most important work happened in the quiet of his private office. He used the very resources meant to fight corruption to ensure that no truth ever reached the light. He had his men monitor every movement of Lawyer Kwarteng’s team. He intercepted their calls and read their emails under the guise of “national security.” He was the hunter who had convinced everyone he was the hound.

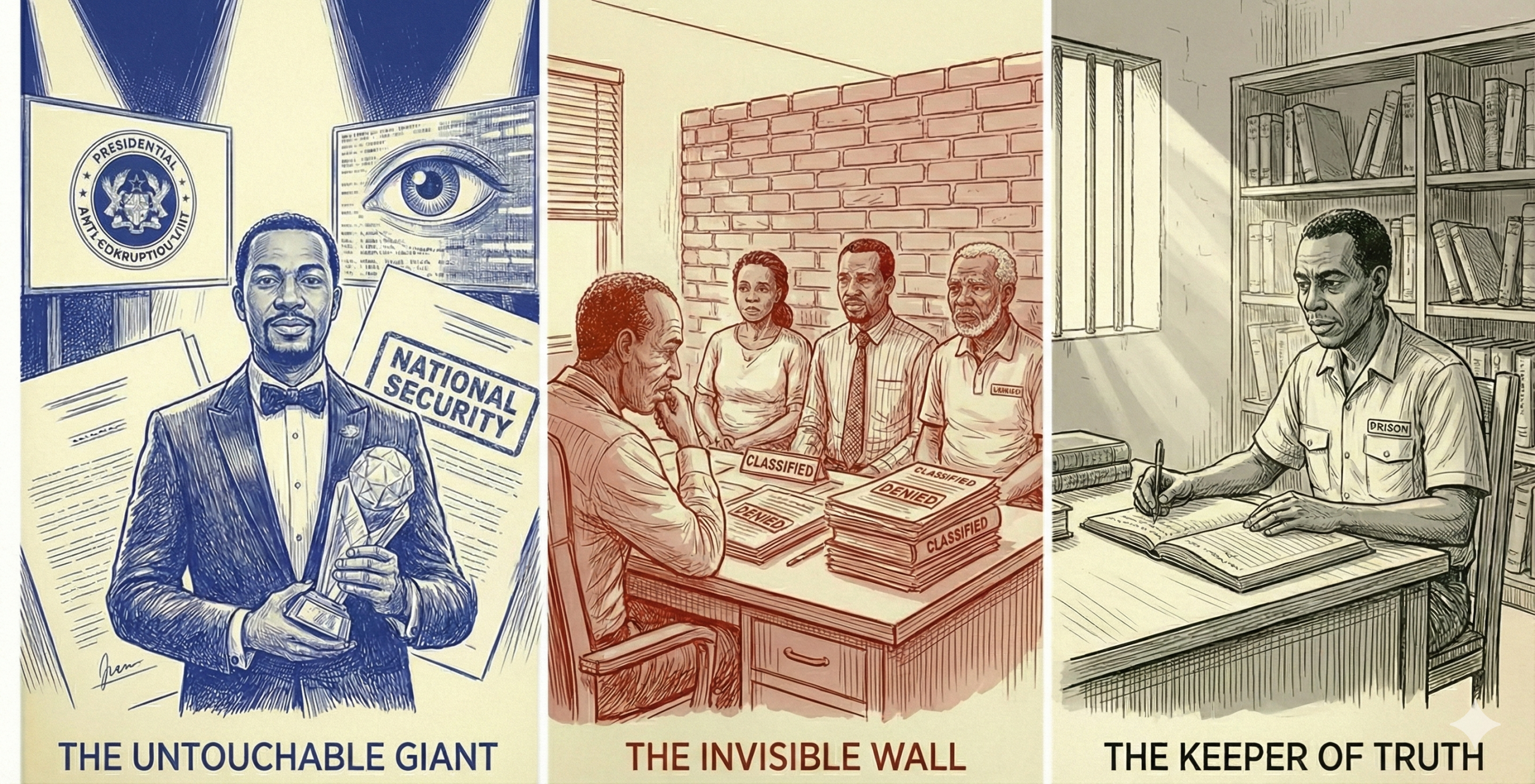

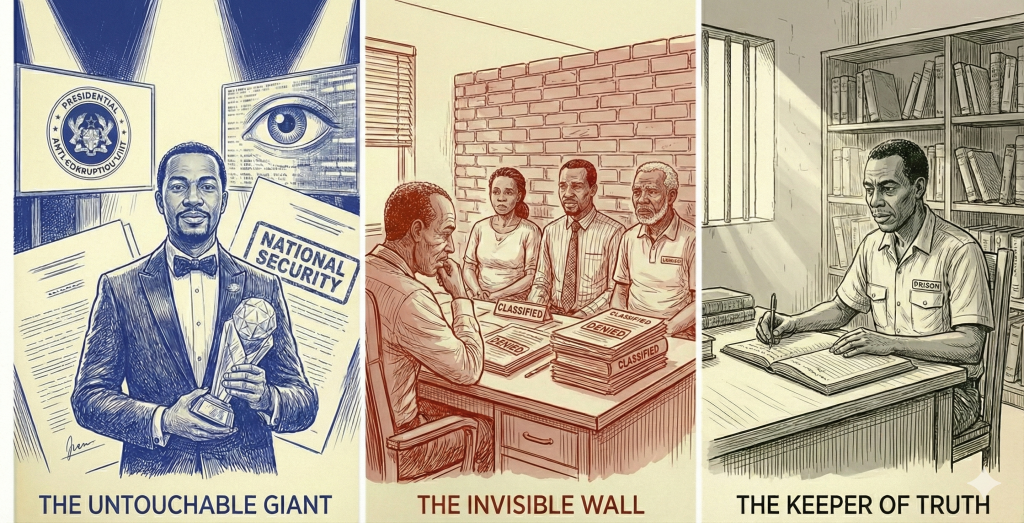

Four hours away, in the dim, paper-choked office of Lawyer Kwarteng in Kumasi, the mood was one of mounting despair.

“It’s been three months, and we are still staring at a wall,” Kwarteng said, his voice heavy with frustration. He was flanked by Mr. Mensah and Uncle Gyasi. Spread across the desk were reports from the two additional Private Investigators they had hired, men who had risked their reputations to find the crack in the facade.

“We find a lead, and it vanishes,” the senior PI, a man named Boateng, explained. “We traced the ownership of those five logistics companies. We found a trail of shell corporations registered in the Virgin Islands. But when we tried to dig into the local bank accounts that funded them, the banks refused to talk. They cited ‘National Security’ directives from the Anti-Corruption Unit in Accra. They say the accounts are part of an ongoing sensitive investigation.”

Mr. Mensah slammed his fist on the table. “Ongoing investigation? They are using the law to hide the crime! We know Asamoah Snr owned the company that owned those trucks. We know Kojo signed the waybills. But every time we reach for the proof, it’s like grabbing smoke.”

“The long arms of the Asamoahs are everywhere,” Kwarteng muttered, leaning back in his chair. “They aren’t just plugging holes; they are rebuilding the whole dam. Jude is the head of the unit that is supposed to be helping us. Every lead we give the police is handed straight to him.”

Uncle Gyasi looked at the photos of Kwesi’s father in the hospital. “And my brother… he asks for Kwesi every day. He thinks the ‘long trip’ is almost over. How much longer can we keep this lie alive?”

The silence in the room was suffocating. They had the truth, but they lacked the power to speak it. They had a mountain of suspicion, but Jude Asamoah owned the mountain.

As the third month drew to a close, the “Political Corridor” had become a tomb for Kwesi Dankwa’s innocence. Jude sat in his office in Accra, looking out over the city he had conquered, the crystal award reflecting the city lights. He was the hero of the hour, the man of the year. And deep in the archives of his mind, he made sure the file on Kwesi Dankwa was marked ‘Closed,’ ‘Classified,’ and ‘Buried.’ The golden return had become a perfect, high-society trap, and for those outside the walls, the hope of an appeal was beginning to flicker and die in the shadow of an untouchable giant.

A few months later, the air conditioner in Lawyer Kwarteng’s office was doing little to cut through the oppressive humidity of the Kumasi afternoon. On his desk, the latest reports from the Private Investigators lay fanned out like a losing hand of cards. For months, they had chased and followed leads into dead ends, and watched as every door in the city, and eventually the capital, slammed shut in their faces.

Mr. Ofori, Mr. Mensah, and Uncle Gyasi sat in a semi-circle before the desk, their faces etched with the fatigue of a year’s worth of false hope. Gyasi’s hands were clasped tightly in his lap; he had only recently returned from Ejisu, where the quiet life of the village had done little to ease the storm in his mind.

“I didn’t bring you here to sugarcoat the situation,” Kwarteng began, removing his spectacles and rubbing the bridge of his nose. “We have to be honest with ourselves. The terrain has changed. When we started this, we were fighting a local prosecutor and a corrupt accountant. Now, we are fighting a system that has canonised our enemy.”

Mr. Mensah leaned forward, his voice strained. “The PIs… they found nothing? Not even a trace of the truck payments?”

“They found the traces, Mensah,” Kwarteng sighed. “They found the offshore accounts. They found the shell companies. But the moment they tried to link those accounts to the logistics fleet, they hit a digital wall. Jude Asamoah’s new Anti-Corruption Unit has flagged those specific entities under a ‘National Security’ directive. By law, the banks cannot release that data to anyone without a warrant signed by… well, by Jude or his superiors in Accra.”

“It’s a circle,” Mr. Ofori whispered, his voice trembling with a mix of anger and grief. “The man who is the one leading the investigation is the person we are trying to find evidence against. How can this be justice?”

“It isn’t justice, Ofori. It’s politics,” Kwarteng replied. “In the current climate, Jude is untouchable. He has the President’s ear and the public’s admiration. To challenge him now, with nothing but our suspicions, would not only fail Kwesi, it would likely land us in a cell beside him.”

The room fell into a heavy, suffocating silence. The realisation that they had reached a dead end was a physical blow. For months, the belief in a ‘smoking gun’ had kept them going. Now, that gun was locked in a vault to which only the murderer held the key.

“So, what do we do?” Gyasi asked, his voice cracking. “Do we just tell Kwesi he’s staying there for twenty years? Do we tell Opanyin that his son is gone?”

Kwarteng looked at the men, his eyes filled with a weary kind of resolve. “We do the only thing we can. We wait. We keep the file open. We wait for the ego of these men to trip them up. Power like Jude’s eventually creates its own gravity, and eventually, it pulls in something it can’t handle.”

He stood up, walking to the window to look out at the bustling streets of Adum. “There is an old saying, my friends. The wheels of justice grind slowly. Sometimes they grind so slowly that we think they have stopped altogether. But they never stop. One day, the wind will change. Until then, we must be the keepers of the truth.”

“But Kwesi is wasting away,” Mensah argued.

“Kwesi is surviving,” Kwarteng corrected him. “And as long as he is surviving, there is a chance. For now, the legal battle is on ice. But the war… the war is just beginning its long dry season.”

As the three men walked out into the heat of Kumasi, they felt the weight of the lawyer’s words. The “Institutional Wall” was not made of stone or brick; it was made of silence, classified files, and the absolute power of a man who had become a hero by way of a lie. The first year of Kwesi’s sentence was coming to a close, and for the first time, the path back to the light seemed entirely invisible.