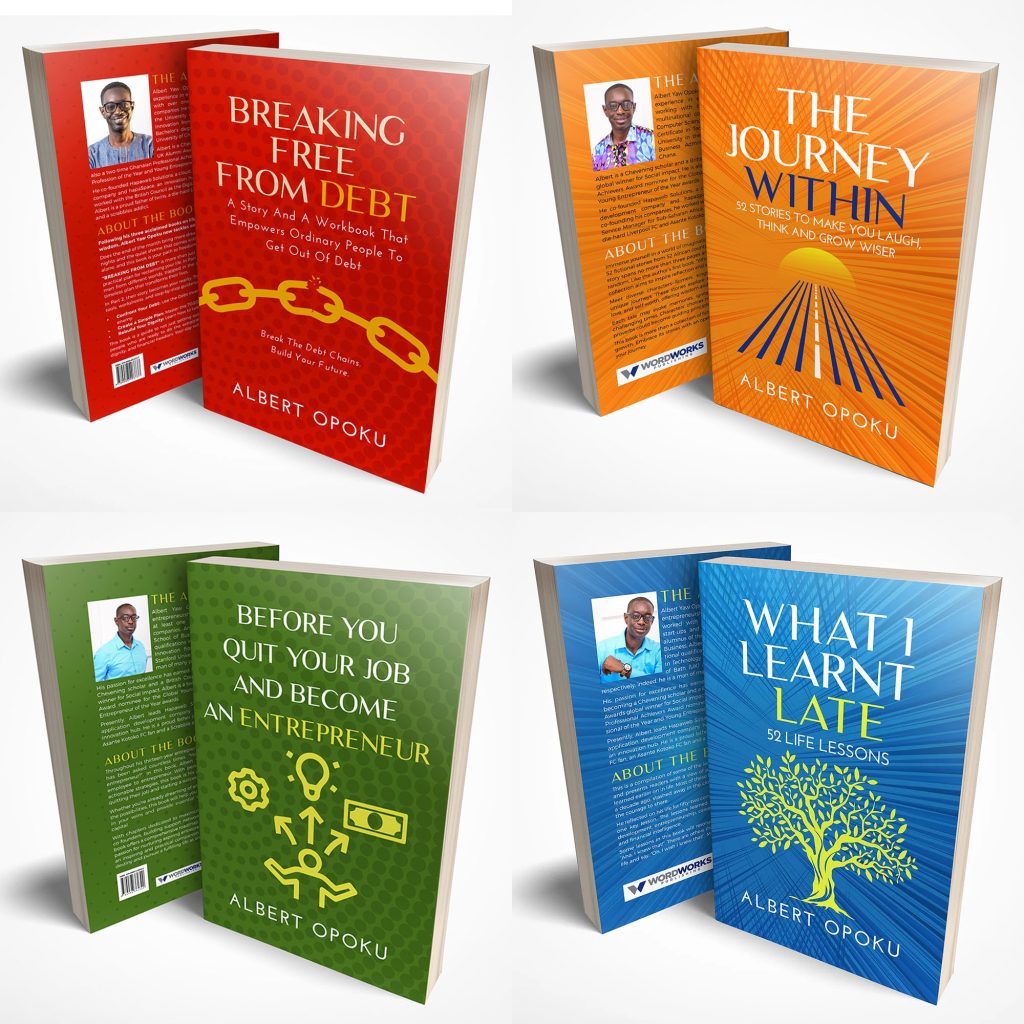

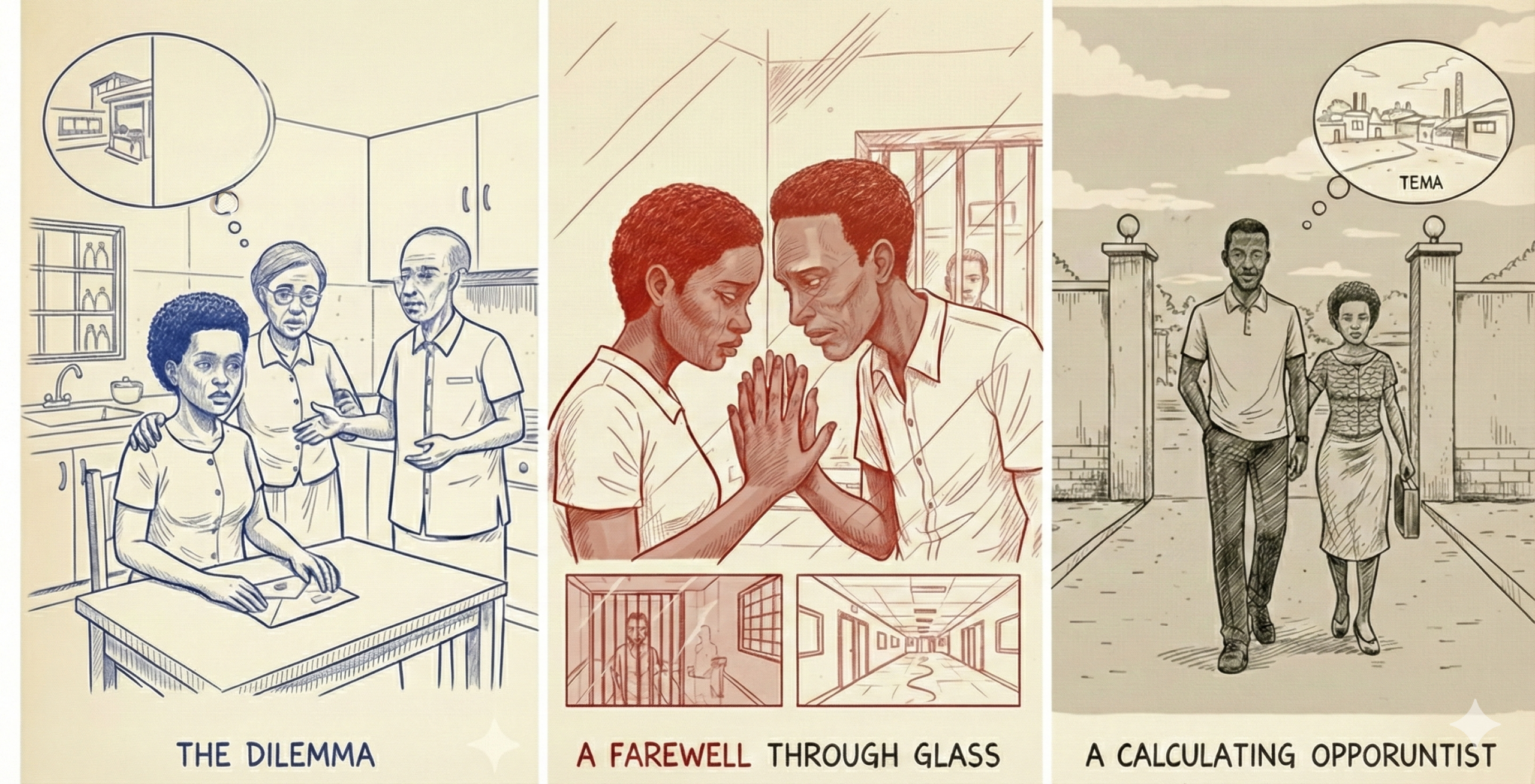

The second month began with a spectacle of such opulence that it felt like a collective fever dream. The wedding of Jude Asamoah Jnr and Cynthia Boateng was not merely a ceremony; it was a coronation. Held at the prestigious Ridge Conference Centre in Accra, followed by a reception that spilled across the grounds of the grand edifice, the event drew the very marrow of Ghanaian society.

President Jemila Alhassan occupied the front seat, her presence a silent endorsement of the groom’s new authority. Paramount chiefs in heavy, gold-threaded kente sat alongside Supreme Court justices, their conversations a low hum of power.

Jude stood with his bride, looking every inch the national hero. Beside him, Asamoah Snr stood tall, his chest puffed with a pride that was as fraudulent as it was immense. A few weeks ago, the final papers had been signed: Asamoah Snr had officially retired, his logistics empire sold for millions of dollars that ensured the family’s wealth was now “clean” and diversified. To the world, he was a successful entrepreneur entering a well-deserved retirement.

“I am so proud of you both,” Justice Boateng whispered as the couple signed the marriage register. He squeezed Jude’s shoulder, a gesture of absolute acceptance. “You have achieved the one thing I value most: a life without reproach.”

Jude managed a smile, though the words felt like iron filings in his throat. As they walked down the aisle to the thunderous peal of the organ, he saw a sea of admiring faces. He was the golden son of the republic. He had outrun the shadow of his father’s trucks. He had buried the only man who could speak the truth.

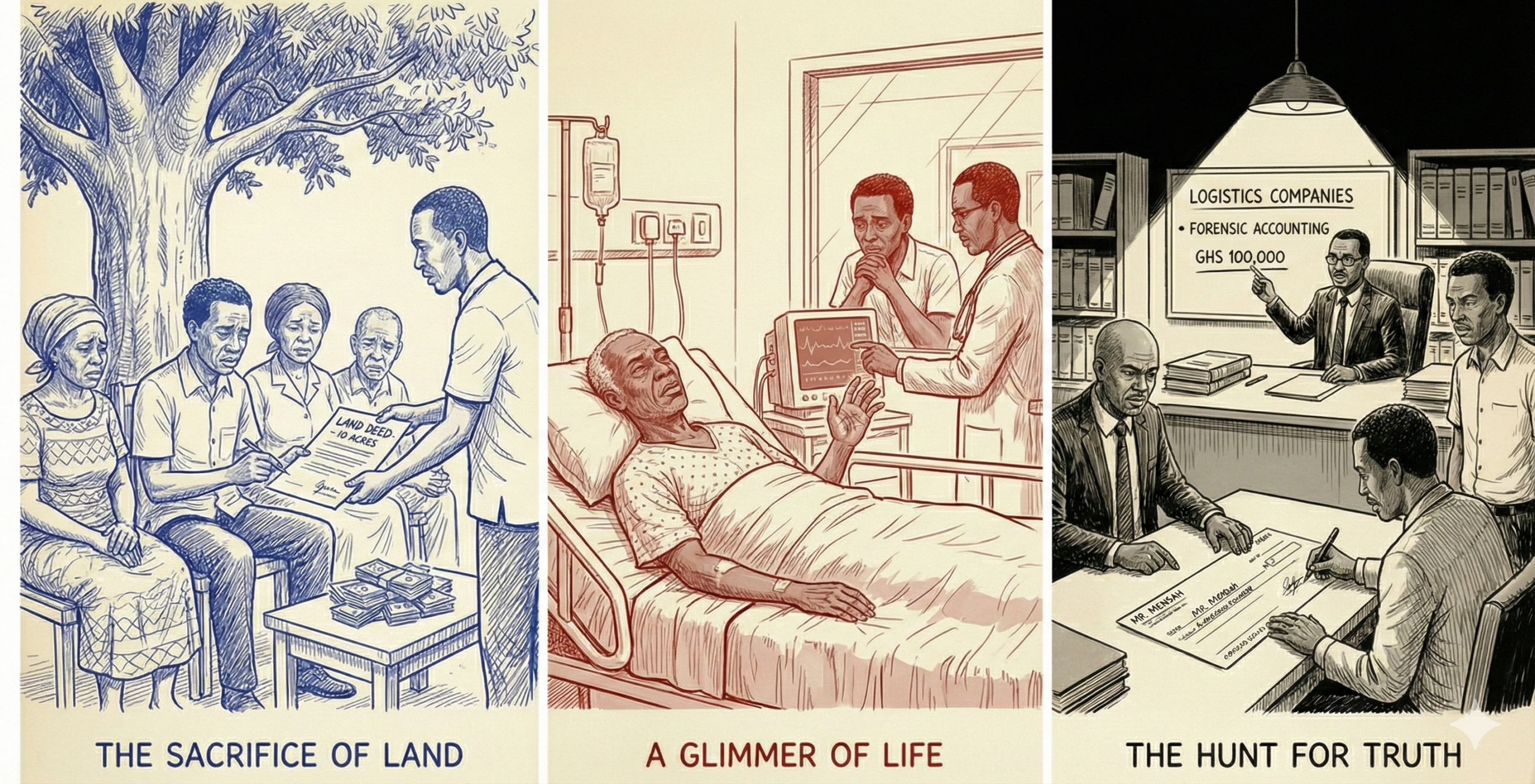

But miles away, in the sterile, hum of the Noguchi Memorial Institute in Accra, a different kind of miracle was unfolding.

Uncle Gyasi sat by the bed, the constant, rhythmic beep of the monitors the only soundtrack to his vigil. He had spent the last of the land-sale money on this specialised care, praying that the experimental drugs would find a way through the fog of the stroke.

Suddenly, the silence was broken.

“Gyasi…”

The voice was a ragged whisper, a sound like dry leaves skittering across a tombstone, but it was unmistakable. Gyasi’s head snapped up. Opanyin Dankwa was awake, his left hand twitching against the white sheets. His eyes, though clouded with pain, were focused.

“Opanyin! You are awake!” Gyasi cried, leaning forward and clutching his brother’s hand.

The old man’s jaw worked, his right side still a heavy, uncooperative weight. He struggled for a moment, his forehead creasing with a monumental effort. Then, his first words since the “Knocking” ceremony emerged, clear and heartbreaking.

“My son…” he wheezed. “Kwesi… where is he? Why has he not come?”

Gyasi felt a fresh wave of grief crash over him. How could he tell a man who had just returned from the brink of death that his pride and joy was a number in a cell? He looked at the fragile hope in his brother’s eyes and forced a smile, his own voice trembling.

“Rest, Opanyin,” Gyasi soothed, stroking the old man’s brow. “He is… he is on a long trip. He is working. He will come soon. Just rest.”

Opanyin Dankwa nodded slowly, the effort of speaking having drained his meagre reserves. He drifted back into a fitful sleep, unaware that while he clawed his way back to life, the man responsible for his son’s destruction was dancing at the wedding of the year. The battle lines were hardening: Jude Asamoah had the world at his feet, but in a small hospital room, the one man who loved Kwesi most had found the strength to wait.

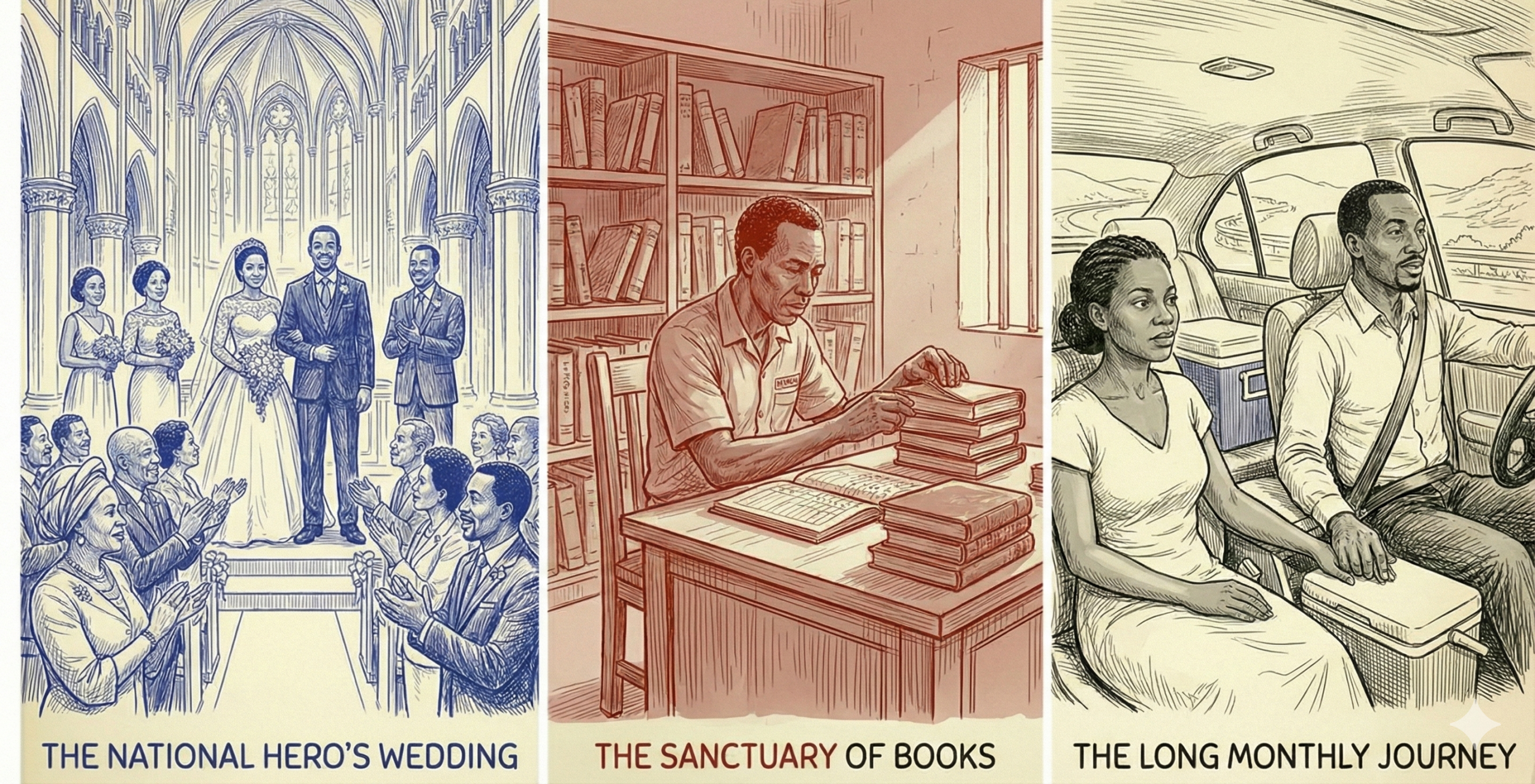

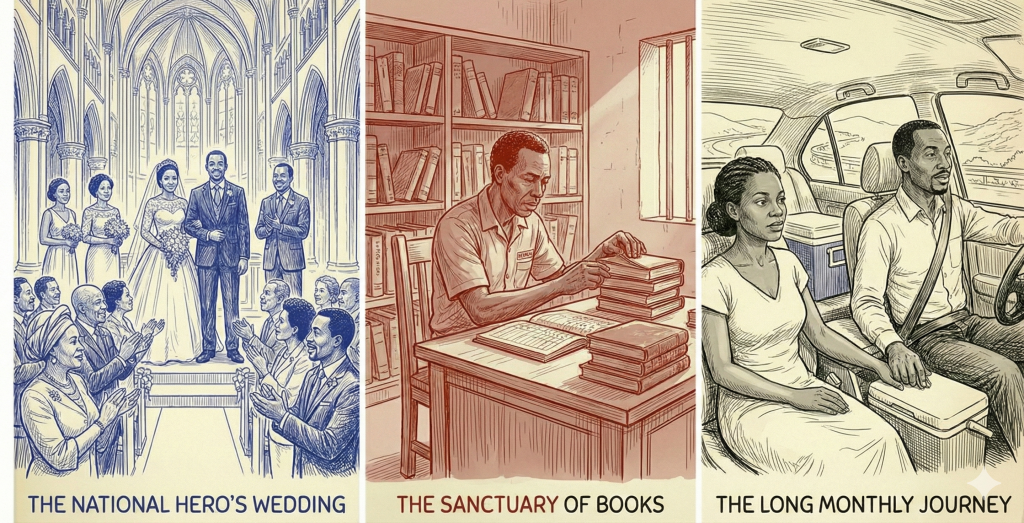

The turn of the month brought a quiet shift in the geography of Kwesi’s incarceration. This was his second month at ACP. Each day, the sensory assault of Cell 4 was replaced, for a few hours, by the heavy silence of the prison library.

Officer Owusu, a man whose uniform was always a size too small and whose eyes held a weary kind of kindness, had been watching the new prisoner. He had seen Kwesi hunched over tattered journals in the yard, oblivious to the shouting matches erupting around him. One afternoon, while Kwesi sat under the meagre shade of the wall, Owusu dropped a small stack of books beside him. They were real books, a battered copy of a world history, textbooks and old, spine-cracked biographies of Kwame Nkrumah and Nelson Mandela.

“You have a thirst for knowledge, 4405,” Owusu said, his voice a low rumble. “

Kwesi looked up, surprised. “Books are the only windows here, Officer.”

Owusu nodded slowly. “The old librarian passed away last week. His heart gave out. The Deputy Warden needs someone to keep the logs. Someone who knows their way around a ledger. Apply for the Library Assistant role. I’ll put in a word.”

Kwesi did not hesitate. Within a week, he was the Keeper of Books. The library was little more than a converted storage room, its shelves sagging under the weight of donated law books from the 70s and dog-eared religious tracts, but to Kwesi, it was a sanctuary. Here, the air was cooler, and the only noise was the rhythmic turning of pages. He began to organise the chaos, categorising the volumes with the same meticulous precision he once applied to cocoa shipments. In the quiet corners of the library, Kwesi Dankwa began to rebuild his mind, one chapter at a time.

While Kwesi found peace in past through books, Abena finally found a home in the present. Through Osei’s “leads,” she had found a room in Community 4, Tema. It was a modest and clean outbuilding owned by a widow named Maame Efua.

Maame Efua, a woman with a laugh that sounded like the crackle of a cooking fire, had taken one look at Abena’s tired eyes and decided the young nurse was more than just a tenant. “You look like my own daughter,” she told Abena, handing her a plate of hot banku on her first night.”

Settling into Tema brought a strange, lonely rhythm. The work at the Children’s Hospital was a constant, exhausting demand, but the nights were worse. She spent them writing letters she knew Kwesi might never see, her pen scratching against the paper in the glow of a small desk lamp.

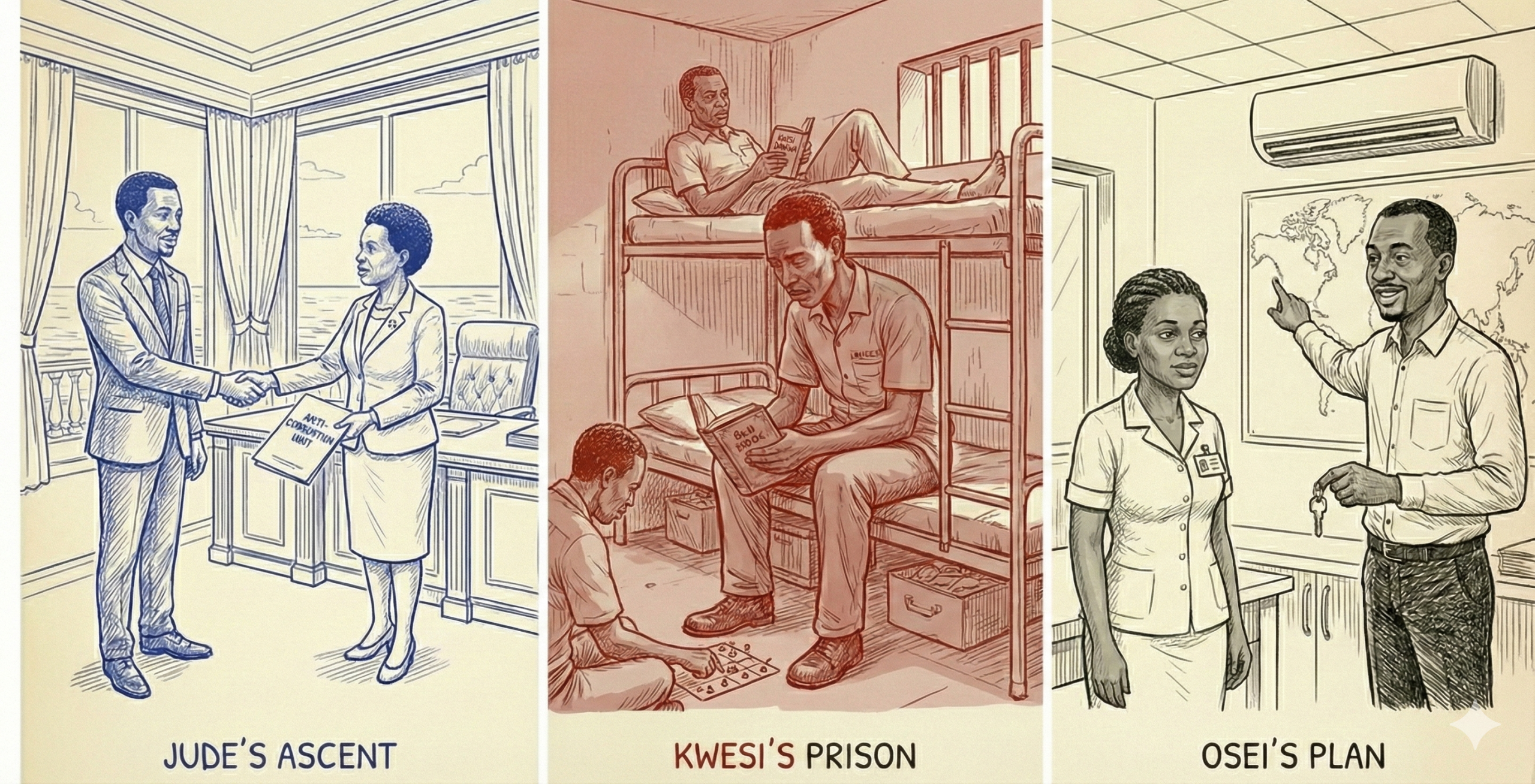

The first Saturday of the month became the anchor of her existence.

“I’m ready, Abena,” Osei said, pulling up to Maame Efua’s gate in a rented Ford. He was dressed in his best casual clothes, looking every bit the successful professional.

“You don’t have to do this every time, Osei,” Abena said, adjusting the strap of the heavy cooler containing the jollof rice she had spent the morning preparing. “It’s a long drive to Kumasi and back.”

“I told you, it’s for safety,” Osei insisted, taking the cooler from her and placing it in the backseat.” Besides, Kwesi is my brother. I have to see him too.”

The journey took six hours, the car winding through the hills and the valleys. Osei talked incessantly, about the harbour, his new job, the important people he was meeting. Abena mostly watched the landscape blur past, her mind already inside the walls of the ACP.

When they arrived, the routine was as cold as ever. Osei sat beside her in the visitation room, his arm often brushed against hers as they waited. When Kwesi appeared, Osei’s face would transform into a mask of deep, performative sorrow.

“Stay strong, brother,” Osei would say, his voice thick with fake emotion. “I am looking after Abena. She is safe with me. Don’t worry about anything outside.” Kwesi would look at them, his fiancée and his cousin, standing together against the world, and feel a twisted kind of gratitude. He didn’t see the way Osei’s fingers lingered on the back of Abena’s chair. He didn’t hear the subtle way Osei took credit for her new housing. He only saw a brother protecting what he had lost. As the monthly visits became a tradition, the chain Osei was weaving around Abena tightened, bit by bit, under the very eyes of the man he had betrayed.