The call came on a Tuesday morning, barely a week after the sentencing. Jude Asamoah was sitting in his office in Kumasi, the silence finally settling over a desk that had been a feverish battlefield for weeks. When his private line rang, a number known only to a few high-level officials, he knew before answering that someone important was calling.

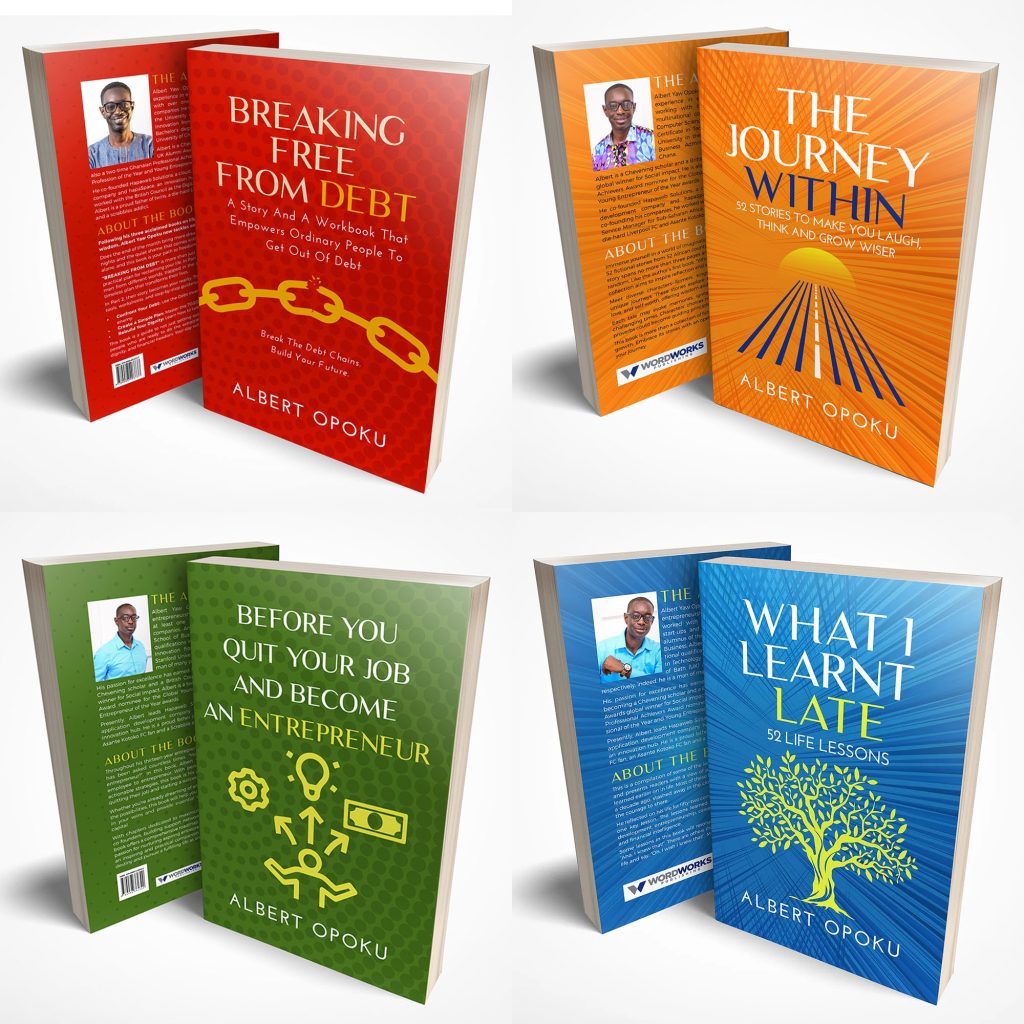

“Mr. Asamoah,” the voice was crisp, carrying the unmistakable authority of the capital. “The Presidency has taken note of your performance in the ‘Cocoa Kingpin’ trial. It has sparked quite a conversation in the Cabinet. You are expected at Nungua Castle tomorrow morning at ten. A government vehicle will meet you at the airport.”

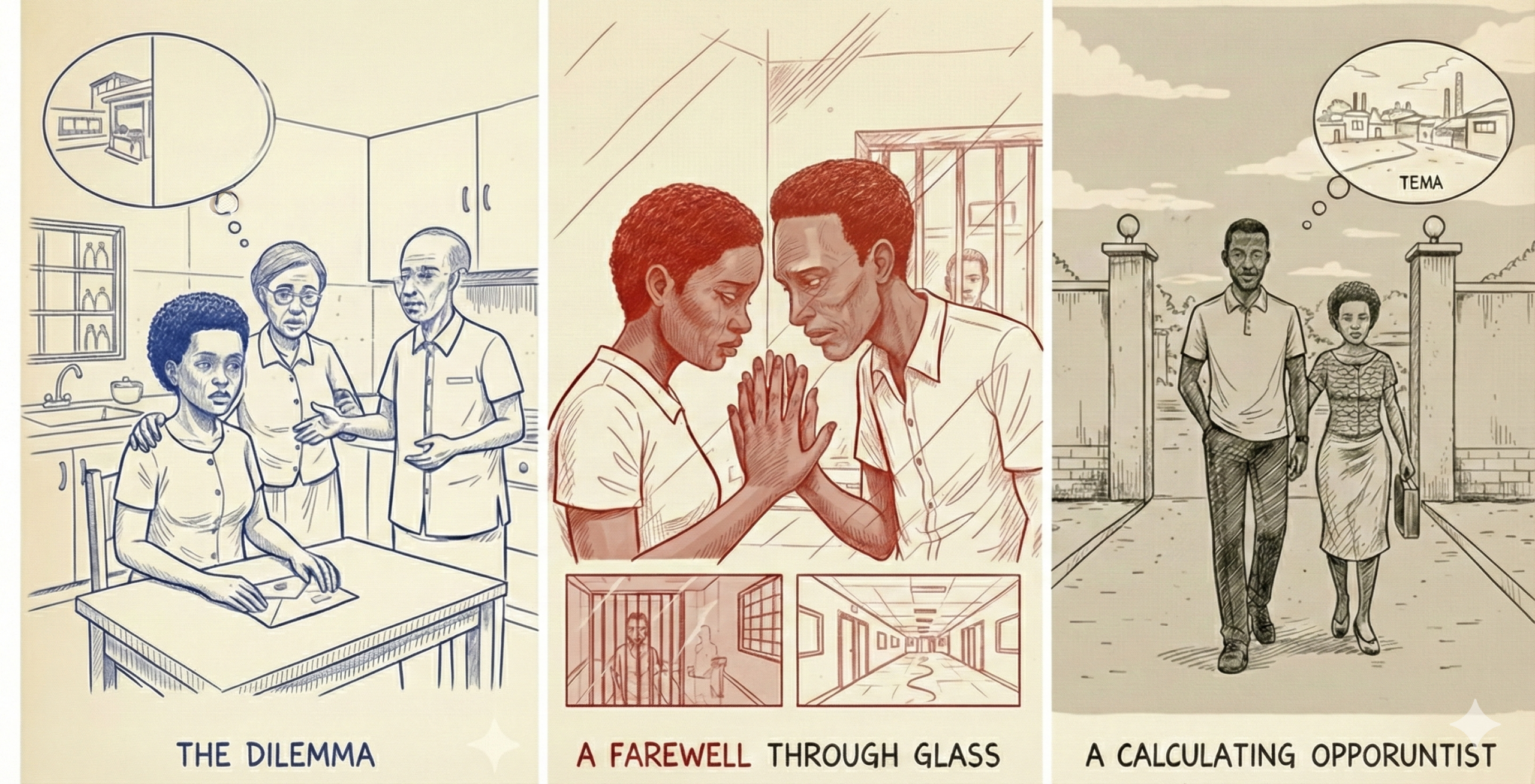

That was how the ascent truly began.

Accra was different from Kumasi. While the Garden City thrived on the steady, rhythmic pulse of trade and tradition, the capital city was a sprawling, humid city of power and ambition. Jude Asamoah sat in the back of a black government Land Cruiser, watching the palm trees blur past along the road. In his hand, he clutched a leather-bound briefing folder. Inside was the final report on the Dankwa case, a document that had become his golden ticket. By the time the car slowed to a halt at the fortified gates of the Castle, Jude had practised his “modest hero” expression a dozen times in the rearview mirror.

He was led through a series of high-ceilinged corridors where the history of colonial governors seemed to linger in the shadows. Finally, he was ushered into a vast, mahogany-panelled office.

President Jemila Alhassan did not look like a woman who was currently wrestling with an IMF-mandated austerity program. She sat behind a desk that looked large enough to host a cabinet meeting, her African print stole draped perfectly over her shoulder. She looked up from a document, her eyes sharp and discerning.

“Mr. Asamoah,” she began, her voice a calm, authoritative melody. “The ‘Cocoa Kingpin’ conviction. A job well done. In these times, when every dollar of revenue counts toward our recovery targets, your diligence has saved the state millions.”

“I was only doing my duty, Your Excellency,” Jude replied, inclining his head just the right amount.

“Duty is a rare commodity,” the President said, standing up to look out at the grey waves crashing against the Castle walls. “The smuggling of our cocoa into the Ivory Coast is a rot. It undermines our sovereignty and our creditworthiness. We need more than just occasional prosecutions. We need a targeted strike.”

She turned back to him, her gaze locking onto his. “I am forming a Presidential Anti-Corruption Unit. Its primary mandate will be the total eradication of cocoa smuggling syndicates. I want you to head it, Jude. You have shown that you are a man of the law.”

Jude felt a surge of adrenaline so potent it made his fingertips tingle. It was better than he had imagined. As head of the Anti-Corruption Unit, he wouldn’t just be prosecuting smugglers; he would be the gatekeeper. He would control the intelligence, the surveillance, and the dossiers. He would be the fox officially commissioned to guard the henhouse.

“I am honoured, Your Excellency,” Jude said, his heart hammering against his ribs. “I will not fail you.”

“I know you won’t. You are Justice Boateng’s future son-in-law. You have a reputation to uphold.”

As Jude walked out of the Castle an hour later, the sun felt blindingly bright. He realised with a chilling clarity that the Shadow Ledger was truly gone, not just the physical book he had burned, but the possibility of its truth ever emerging. Who would investigate the head of the Anti-Corruption Unit?

That evening, he met Cynthia at a high-end restaurant in Cantonments. The terrace was lit by strings of fairy lights, and the sound of a distant saxophone drifted on the breeze.

“To the Director,” Cynthia beamed, raising a glass of chilled champagne. “My father will be proud of you, Jude.”

“To us,” Jude replied, clinking his glass against hers.

“Now that the appointment is official,” Cynthia said, her eyes sparkling with a new intensity, “I think it’s time we set the date. No more delays. We postponed the wedding because of the Dankwa case.”

“Next month,” Jude said, reaching across the table to take her hand. His grip was firm, but his palms were cold. “We’ll marry next month. A clean start for a new life.”

As they sat there, the picture-perfect couple of the new administration, Jude felt the final pieces of his fortress slide into place. He had the power, he had the girl, and he had the mandate of the President. In the dark cells of the Ashanti Central Prison, Kwesi Dankwa was becoming a memory. Here, in the golden light of Accra, Jude Asamoah was becoming a national hero.

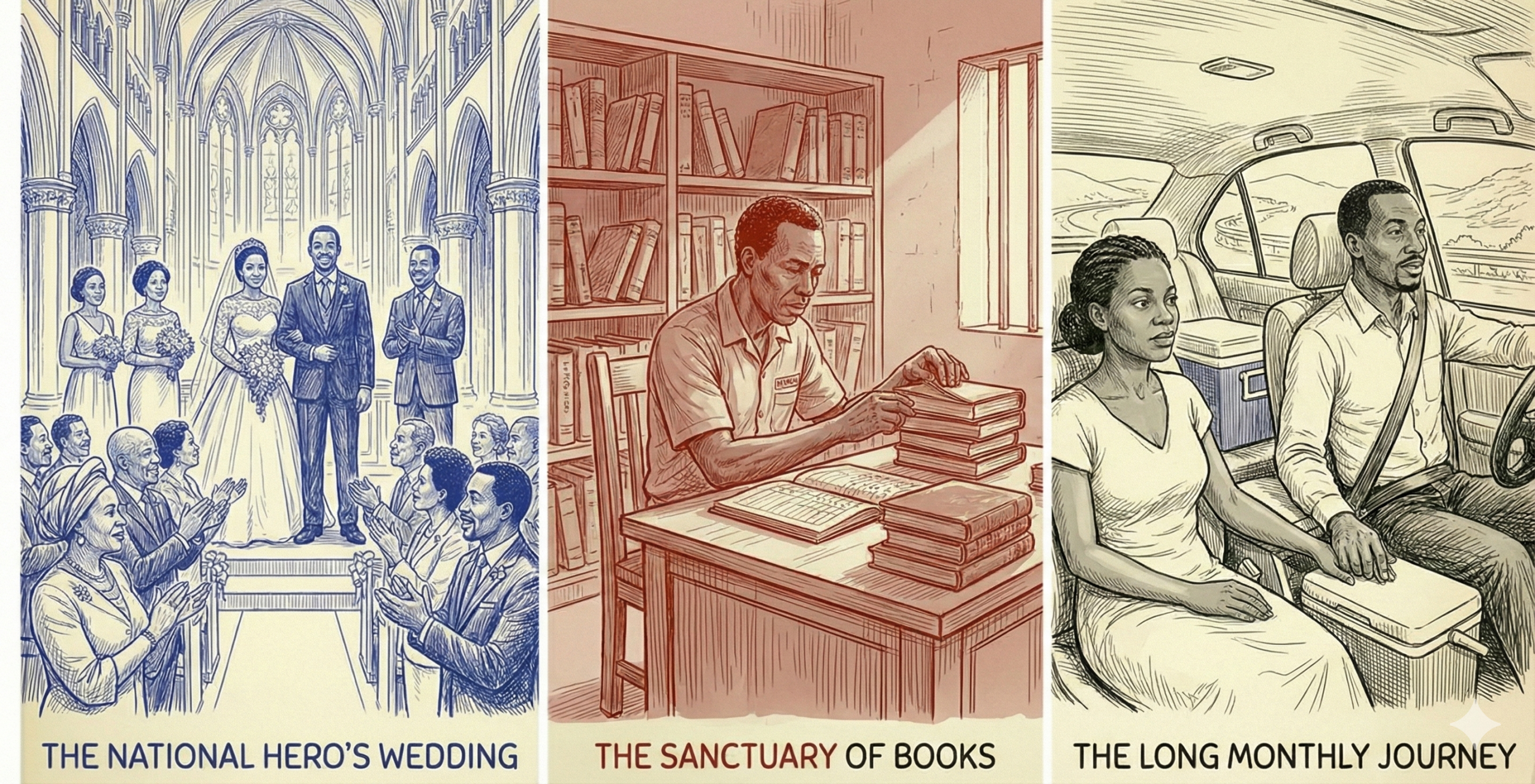

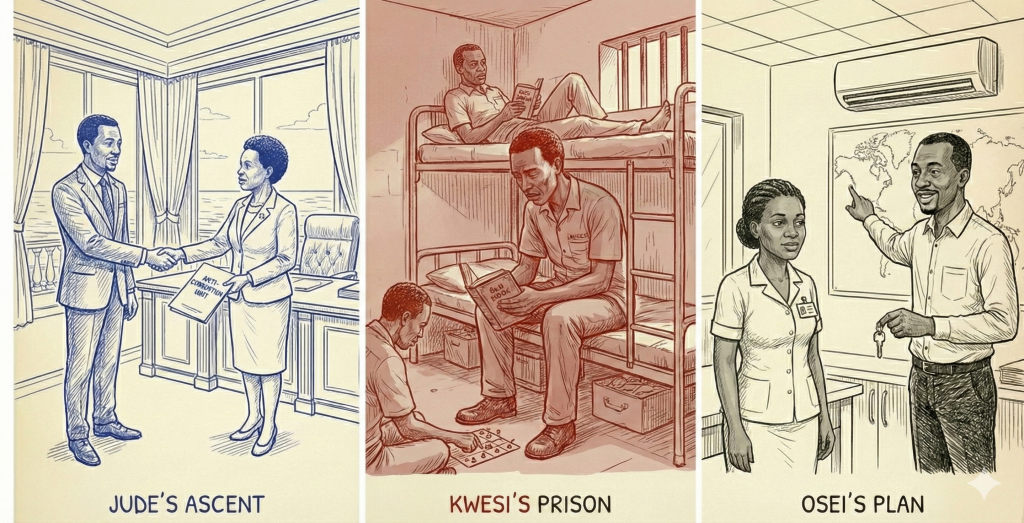

For Kwesi, the first month was a masterclass in the slow erosion of the self. The noise was the worst part, the perpetual, jagged symphony of shouting wardens, the clatter of metal on metal, and the low, guttural chanting of men who had long ago traded their sanity for survival.

He had become a stranger in his own body. He moved when barked at, ate the watery maize porridge without tasting it, and stared at the peeling grey paint of Cell 4 until his eyes gave way to sleep. The only hope connecting him to the outside world was Lawyer Kwarteng.

“We are not resting, Kwesi,” Kwarteng said during a brief, monitored visit. His voice was low, filtered through the hum of the prison’s visitor room. “Mr. Mensah has authorised a team of Private Investigators. They are digging. The data Agorozo provided… it’s a tangle, but we are pulling at the knots.”

Kwesi nodded, but his eyes were hollow. “They move fast, Lawyer. I hear the guards talking. Kojo Danso is the Director now. Jude Asamoah is in Accra, at the Castle. How do you fight the men who are writing the law?”

“You wait for them to make a mistake,” Kwarteng replied firmly. “And you stay alive. That is your only job right now.”

Stay alive. It sounded simple, but in the heat of the cell, life felt like a burden. Kwesi began to seek refuge in the small, tattered library at the end of the block. He requested anything he could get his hands on: outdated textbooks, worn-out novels, old agricultural journals. Anything to drown out the voice in his head that counted the minutes of his twenty-year sentence. He realised that if he couldn’t move his legs beyond the yard, he would move his mind beyond the continent.

Five hours away, in the industrial salt-air of Tema, Abena was fighting a different kind of war. The Tema Children’s Hospital was a whirlwind of activity, a constant influx of patients that left her feet aching and her heart heavy. But the hospital was the easy part.

The housing crisis in Tema was a predator. With her modest nurse’s salary, Abena found herself squeezed into a “Working Girls” hostel, a sprawling, noisy complex where two women shared a single room. Privacy was a luxury she couldn’t afford. She slept with her suitcase locked and her phone under her pillow, the smell of damp laundry and cheap perfume a constant reminder of how far she was from her father’s comfortable home in Patasi.

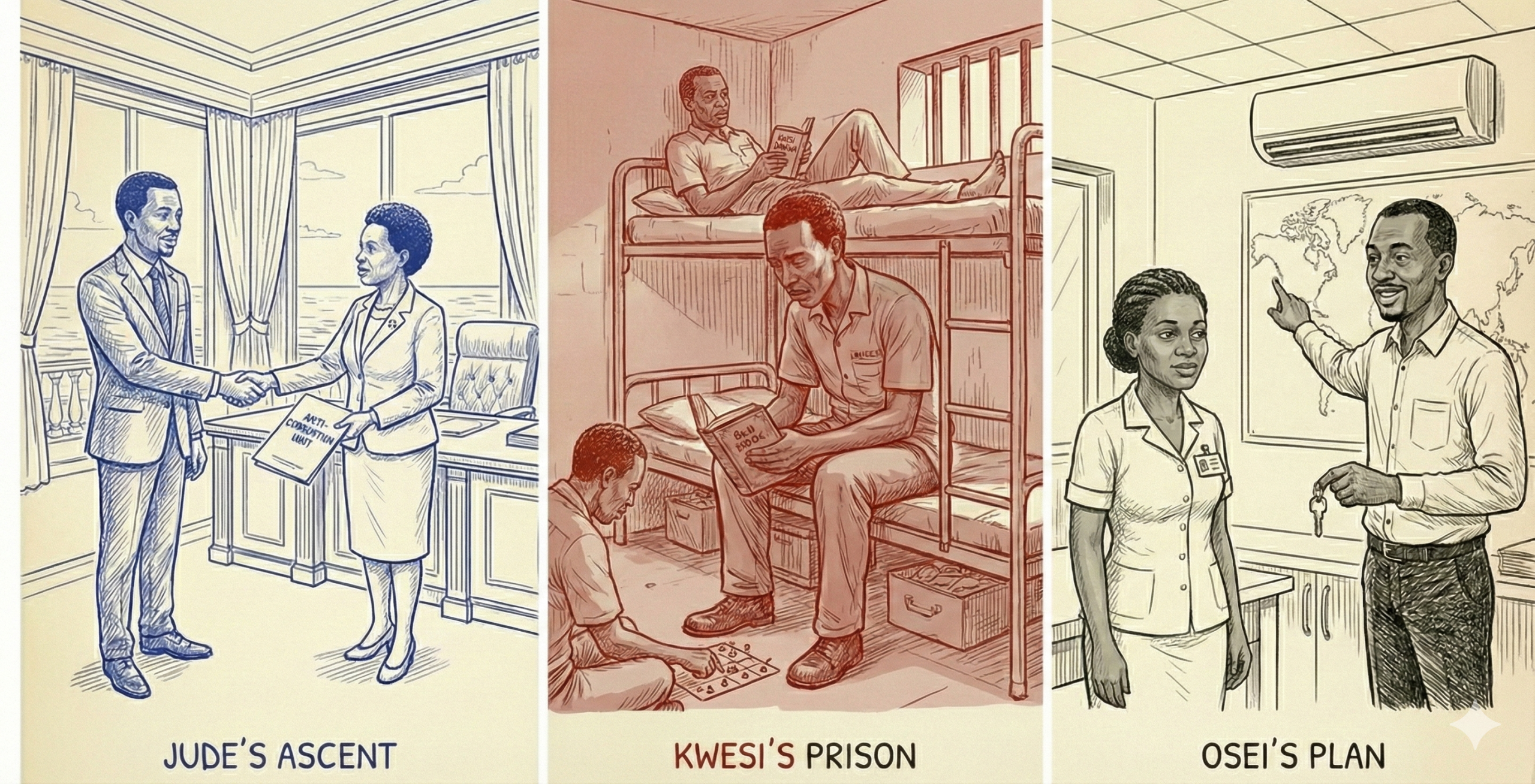

On the other side of Tema, Osei was thriving in his new office at the Tema Harbour logistics wing of the Ashanti Cocoa Buying Company. He wore a crisp white shirt and polished shoes, his desk situated directly under the cool blast of the air conditioner. Kojo had been true to his word; the “transport coordination” role was a goldmine of influence and ease. The monetary “Thank You Officer” was good.

During the week, Abena visited Osei at his office.

“You look like you haven’t slept in a week,” Osei said, leaning back into his swivel chair.

“The hostel is loud, Osei,” Abena replied, sitting across from him. She had come to him out of desperation. “I can’t rest. I can’t think. I spend half my shift just trying to stay awake.”

“I told you, let me help,” Osei said, his voice dropping into that smooth, comforting tone he had perfected. “I’ve been asking around the harbour. There are decent rooms in Community 4. Safe. Quiet. I have a few leads. We’ll go see them this weekend, after your shift.”

He reached out and patted her hand. It was a brotherly gesture, but his eyes lingered on her just a second too long. Abena was too exhausted to notice. To her, Osei was the last piece of home, the only person who understood the weight of the monthly visits she made to the prison in Kumasi.

“Thank you, Osei,” she whispered.

“Don’t mention it,” he smiled. “We are family, Abena. Kwesi isn’t here, but I am. I’ll make sure you’re taken care of.”

As Abena left the office, Osei leaned back in his chair, a slow, predatory satisfaction spreading through him. Every sleepless night she spent in that hostel made her more dependent on him. Every “lead” he found for her was another link in the chain he was weaving around her life. He watched her through the glass partition, a man playing a very long, very patient game.