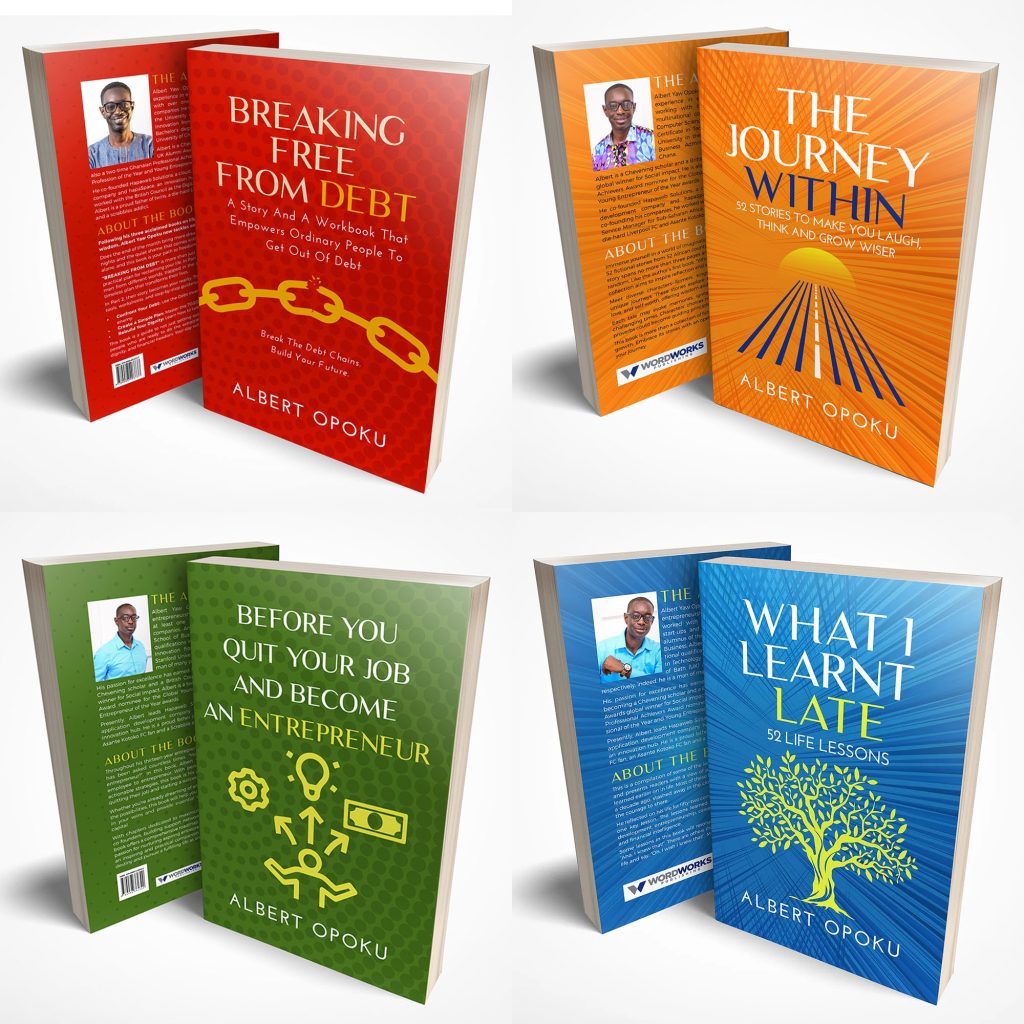

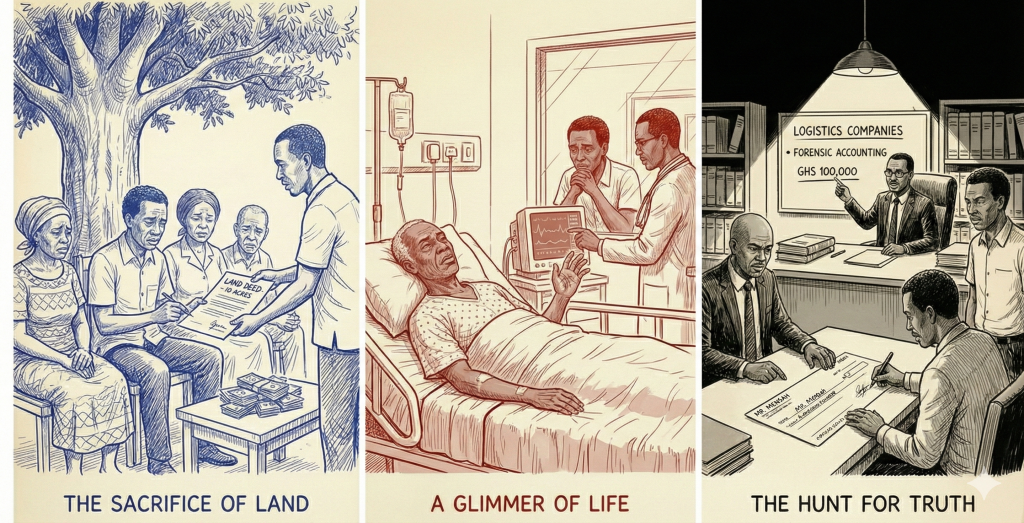

While Osei plotted his move to the coast, a sombre gathering took place under the giant neem tree in the courtyard of the Dankwa family house. Uncle Gyasi stood before the elders of the Abusua, his face lined with the exhaustion of the past month. Beside him, Auntie Yaa and Auntie Esi sat with their heads bowed, their cloths tied tightly around their waists.

“We have gathered GHS 210,000,” Gyasi began, his voice barely a whisper. “But the doctors at Komfo Anokye were clear. The GHS 300,000 for the experimental treatment in Accra is a wall we cannot climb with coins and small notes. And every day Opanyin lies in that bed, his breath grows thinner.”

The silence that followed was broken only by the rustle of the leaves above. In the Ghanaian culture, land is more than soil; it is a sacred trust for the generations yet unborn. To sell it is to cut a limb from the family tree.

“There is the fifty-acre farm in the village,” Auntie Yaa said, her eyes welling with tears. “The one our grandfather left to us. It is prime cocoa land. Our cousin, Agyeman, has already sent word that he knows a buyer, an investor from Accra.”

“Agyeman,” Gyasi spat the name like bile. “He circles us like a vulture. But we have no choice”. Auntie Yaa continues,” He has negotiated the price. GHS 150,000 for the ten out of the fifty acres. We wanted GHS 250,000, but the investor insists that’s what he’s ready to pay.” Gyasi snared “Agyemang surely has a big cut in that, but we are desperate, let’s take it.”

The elders nodded solemnly. It was a theft, just over half of what the land was worth, but they were trading soil for a life. The papers were signed by that evening. The family had lost ten acres of their heritage, but they had gained a chance.

The logistics were swift and brutal. GHS 90,000 was immediately transferred to finalise the treatment fees. The remaining GHS 60,000 vanished into the machinery of private healthcare, an emergency medical air transport to the Noguchi Memorial Institute in Accra and the staggering costs of specialised nursing and high-potency medication.

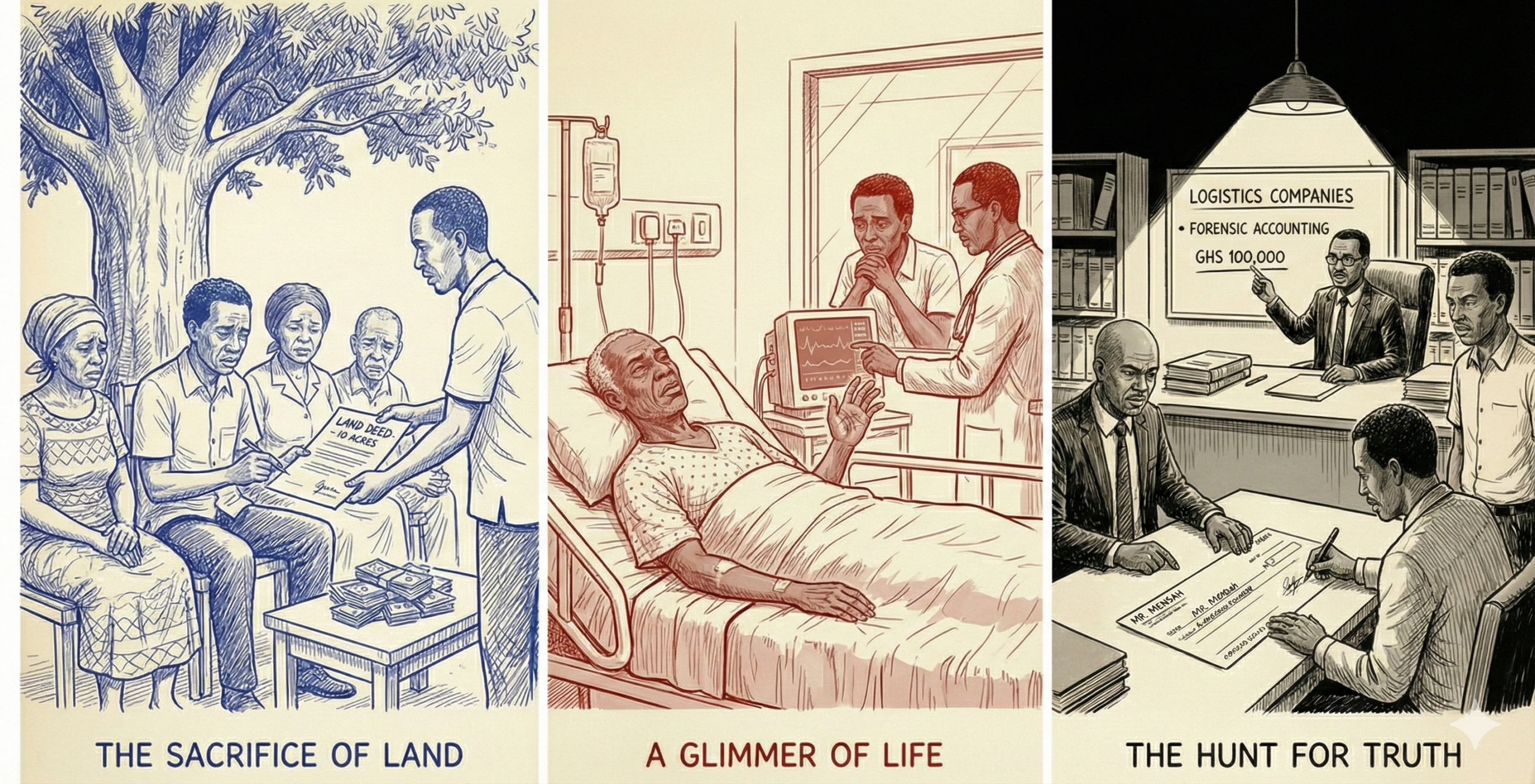

A week later, Gyasi stood in the sterile, air-conditioned hallway of the institute in Accra. Through the glass of the observation room, he watched as Opanyin Dankwa’s hand, the left one, unaffected by the stroke, gave a small, deliberate twitch. The old man’s eyes flickered open, landing on the doctor. He couldn’t speak, the paralysis of his right side still a heavy curtain, but there was a light in his gaze that hadn’t been there in Kumasi.

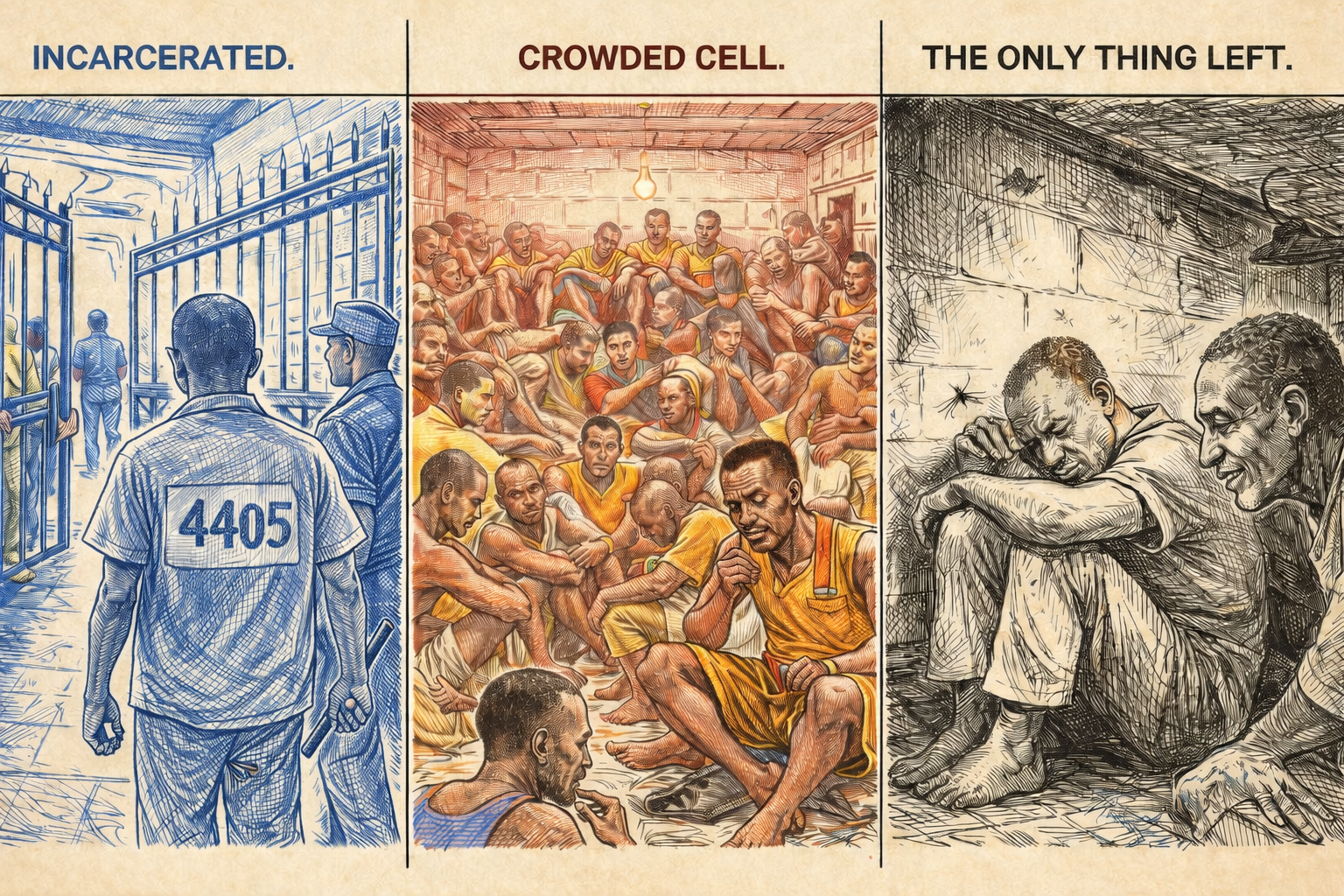

The treatment was working. The sacrifice of the land had bought him time. But as Gyasi looked at his brother, he felt a hollow ache. Kwesi was in a cage, the family farm was gone, and the patriarch lying in the bed was a shadow of his former self. They had survived the first month of sorrow, but the cost of that survival was a debt that could haunt the Dankwas for a generation.

Uncle Gyasi returned to Kumasi on the last Sunday of the month. The journey from Accra was long, the bus rattling through the winding hills of the Eastern Region, but for the first time in weeks, his heart did not feel like a stone in his chest. He had seen his brother breathe without a machine. He had seen a spark of life return to Opanyin’s eyes.

He didn’t go to the family house. He went straight to Patasi, to the Oforis. Mr. Mensah was already there, his face haggard and his eyes red-rimmed. Since his forced leave, the man had become a shadow of the director he once was, spending his days poring over old shipping manifests and his nights in silent prayer.

“He is stable,” Gyasi announced as he entered the living room. “The medicine is working.”

Mr. Ofori let out a long, shaky breath. “By God’s grace. It is the only light we have had.”

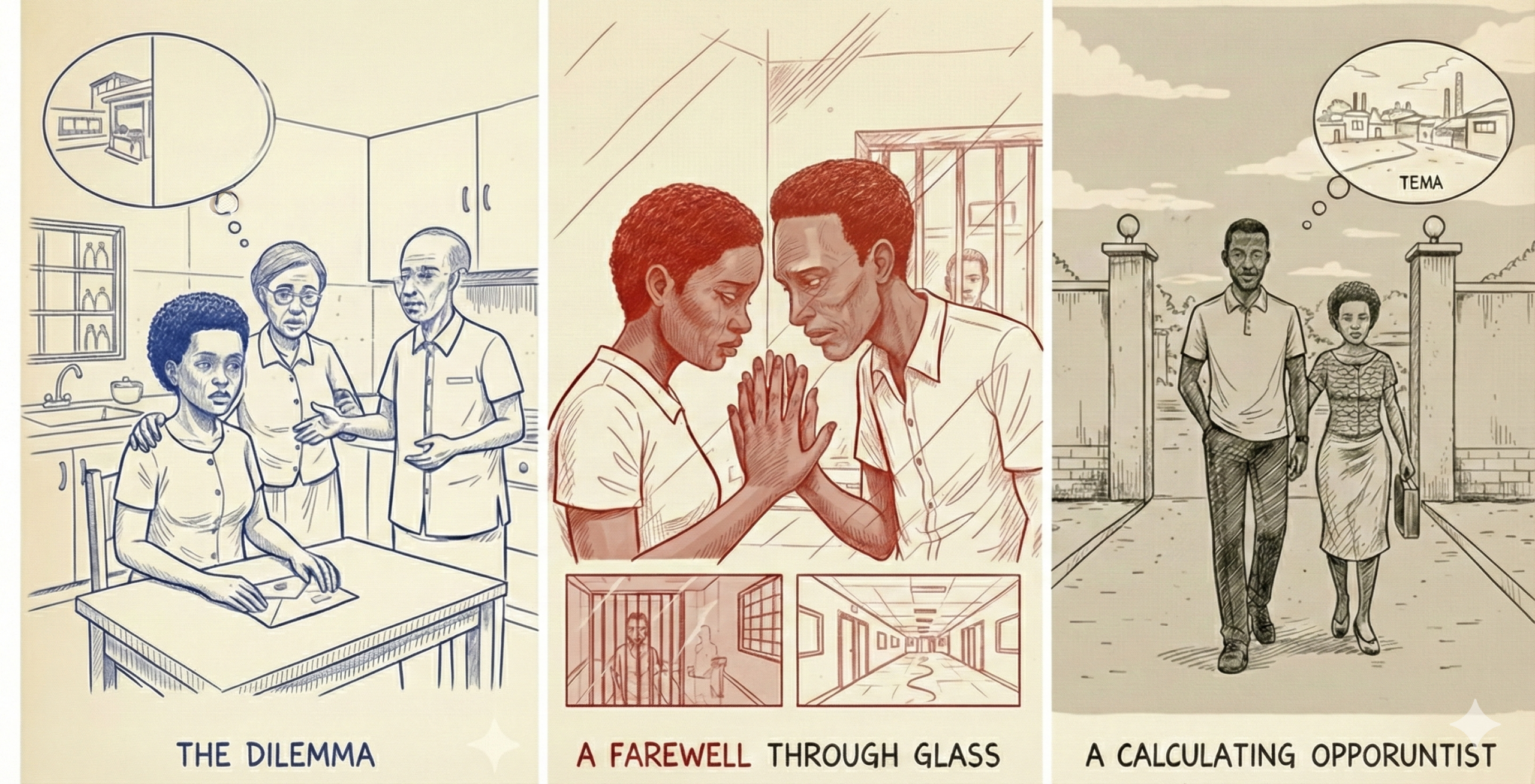

“But it is not enough,” Mr. Mensah said, standing up. “Kwesi is rotting in Cell 4 while the ones who framed him are measuring their new offices for curtains. I spent the morning at the archives before they changed the locks. Kojo has scrubbed everything, Gyasi. Every digital footprint, every waybill. He is thorough.”

“That is why we are here,” Mr. Ofori said, grabbing his car keys. “Lawyer Kwarteng is waiting for us in Adum. He says he has a path forward, but it will require more than just prayers.”

The three men drove to Adum in silence. The city was quiet on a Sunday evening, the vibrant chaos of the market replaced by a sombre, grey twilight. Lawyer Kwarteng’s office was the only light burning in the building. Inside, the lawyer was surrounded by stacks of legal tomes, his “K10PS” strategy now replaced by a single, focused objective.

“We have reached a wall with the current appeal,” Kwarteng began, not beating around the bush. “The court will only entertain a retrial if we produce ‘fresh and compelling’ evidence that was not available during the first trial. Right now, all we have is character testimony. In the eyes of the law, that is a whisper against a storm.”

“What about the truck numbers Agorozo gave us?” Gyasi asked.

“They are just numbers on a page,” Kwarteng sighed. “We know those trucks moved cocoa. We don’t know who paid for the fuel. We don’t know who signed the release forms. We need to go deeper than the manifests.”

He leaned forward, his expression grave. “I am suggesting we hire two additional Private Investigators. Men who specialise in forensic accounting and corporate tracking. One based here in Kumasi, and one in Accra, to look into the bank accounts and other documents used as evidence during the trial. “

“The cost?” Mr. Ofori asked.

“Significant,” Kwarteng admitted. “It will be another GHS 100,000 for the initial retainers. They will dig into those five logistics companies. They will find the real owners. They will find the money trail that leads away from Kwesi and toward the boardroom.”

Mr. Mensah didn’t hesitate. He pulled out a chequebook, his hand steady. “I will pay it. I have my gratuity and my savings. If I have to spend every pesewa I have ever earned to see Kwesi walk free, I will do it.”

He signed the cheque and handed it to Kwarteng.

“The PIs will start tonight,” Kwarteng said, a flicker of hope returning to his eyes. “We are going hunting, gentlemen. If there is a rot in those logistics companies, we will find it.”

As the three men walked out of the office and into the cool Kumasi night, the month of sorrow was officially over. The tragedy had settled, the pieces were in place, and the battle for the truth had shifted from the courtroom to the shadows. Kwesi was in prison, but he was no longer alone in the dark. There was hope – hope that justice would be served.