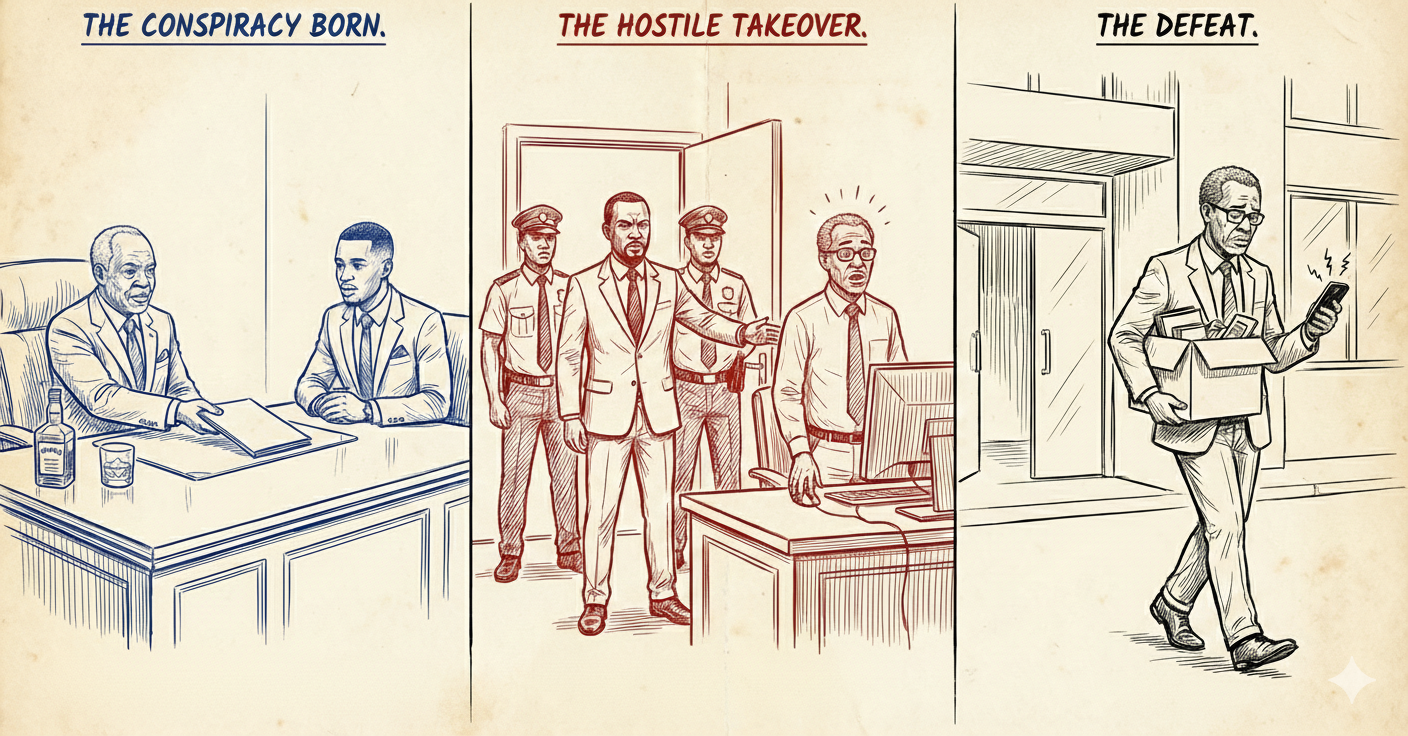

The air conditioner in Lawyer Kwarteng’s office hummed with a low buzz, the only sound in the room besides the scratching of his pen. It was late Wednesday night. By now, Kwarteng usually had his defence strategy mapped out with military precision—his famous “K10PS” (Kwarteng’s 10-Point Strategy). But tonight, looking at the sheet of paper before him, the list was sparse, the ink looking hesitant on the page.

He felt like a man going into a sword fight armed only with a fruit knife. The two weeks given by the court had evaporated. His private investigator had worked tirelessly, speaking to colleagues, neighbours, and drivers. The consensus on the streets was clear: Kwesi Dankwa was an honest man. But the court did not trade in street gossip; it traded in evidence.

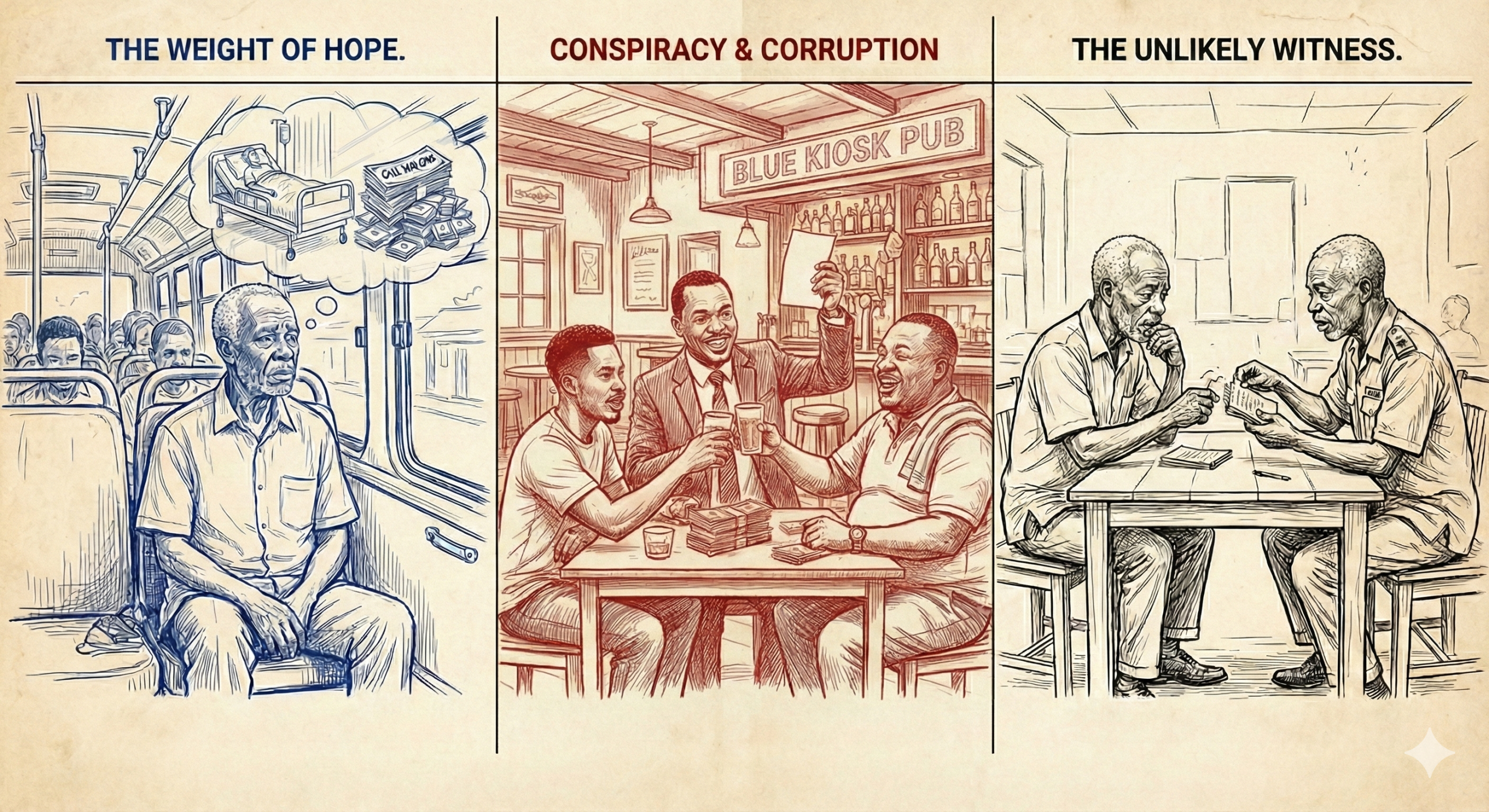

And the evidence against Kwesi was a fortress. Spread across Kwarteng’s mahogany desk were copies of documents provided by the prosecution: vehicle registration records showing three cars registered in Kwesi’s name; deeds for two houses in upscale neighbourhoods; bank statements showing massive deposits. His paralegals had verified them; they were authentic documents, even if the reality they depicted was a lie. Kojo and Asamoah Snr had been thorough; they had not just faked documents, they had corrupted the official registries.

Beside these lay the list of truck numbers provided by Agorozo. It had proven to be a riddle without an answer. They had traced the trucks to five different logistics companies, but the trail went cold there. There was no direct link to Kojo, no smoking gun connecting them to the theft. It was just a list of trucks that moved cargo.

Kwarteng sighed, rubbing his temples. He had lost his star witnesses. Three senior managers, members of Mensah’s “Eagle Eye” team, had backed out, terrified by the wave of dismissals and transfers. Who could blame them? Testifying for Kwesi was now synonymous with professional suicide. He was left with character witnesses: Mr Mensah, Agorozo, Uncle Gyasi, Auntie Esi, and Maame Serwaa. Good people, but they could only speak to who Kwesi was, not what he did.

He picked up his pen and stared at his “K10PS” list:

- Request for continuance.

- Attack the credibility of the prosecution’s evidence.

- Cross-examination of hostile witnesses.

- Character witnesses.

- Evidence of frame-up: None.

- [Nothing]

- [Nothing]

- [Nothing]

- [Nothing]

- Plead for leniency.

It was a list of desperation. His best hope for tomorrow was not an acquittal; it was a delay. He needed more time to find the cracks in Jude Asamoah’s fortress.

Thursday morning broke over Kumasi with a heavy, humid heat. The Circuit Court was buzzing. The trial of the “Cocoa Kingpin,” as the morning papers had dubbed Kwesi, had drawn a crowd that spilled out of the courthouse and into the street. Hawkers sold bottled water, cheap kebabs, Tea-bread and butter, ice kenkey and plantain chips to the curious onlookers, while media crews from every major radio and TV station in the city jostled for position near the entrance.

The case of “The Cocoa Syndicate” had captured the public imagination, fuelled by sensationalist reporting. Inside, the courtroom was a pressure cooker of tension. The Oforis and the Dankwas sat huddled together on the left, a sombre island of grief in a sea of murmuring spectators. Uncle Gyasi sat with his head bowed. Osei was present, wearing a sombre suit that did not quite fit, playing the role of the concerned cousin to perfection, consoling the grieving “wife-to-be” as he held Abena’s hands.

On the other side of the aisle, the conspirators sat like vultures waiting for a feast. Kojo Danso, now the Regional Director, wore a suit that cost more than Kwesi’s monthly salary. Three rows behind him, Agyeman wiped sweat from his face with a faded towel, his eyes darting nervously.

Mr Mensah sat a few rows in front, a man defeated but not broken, watching the proceedings with a burning intensity. Cynthia Boateng was there too, seated in the front row, ostensibly to support her fiancé, but perhaps also to witness the man she was about to marry at his best legal performance. Asamoah Snr was absent, but his shadow loomed large; Charles Edu sat in the back, his eyes recording every detail for his master.

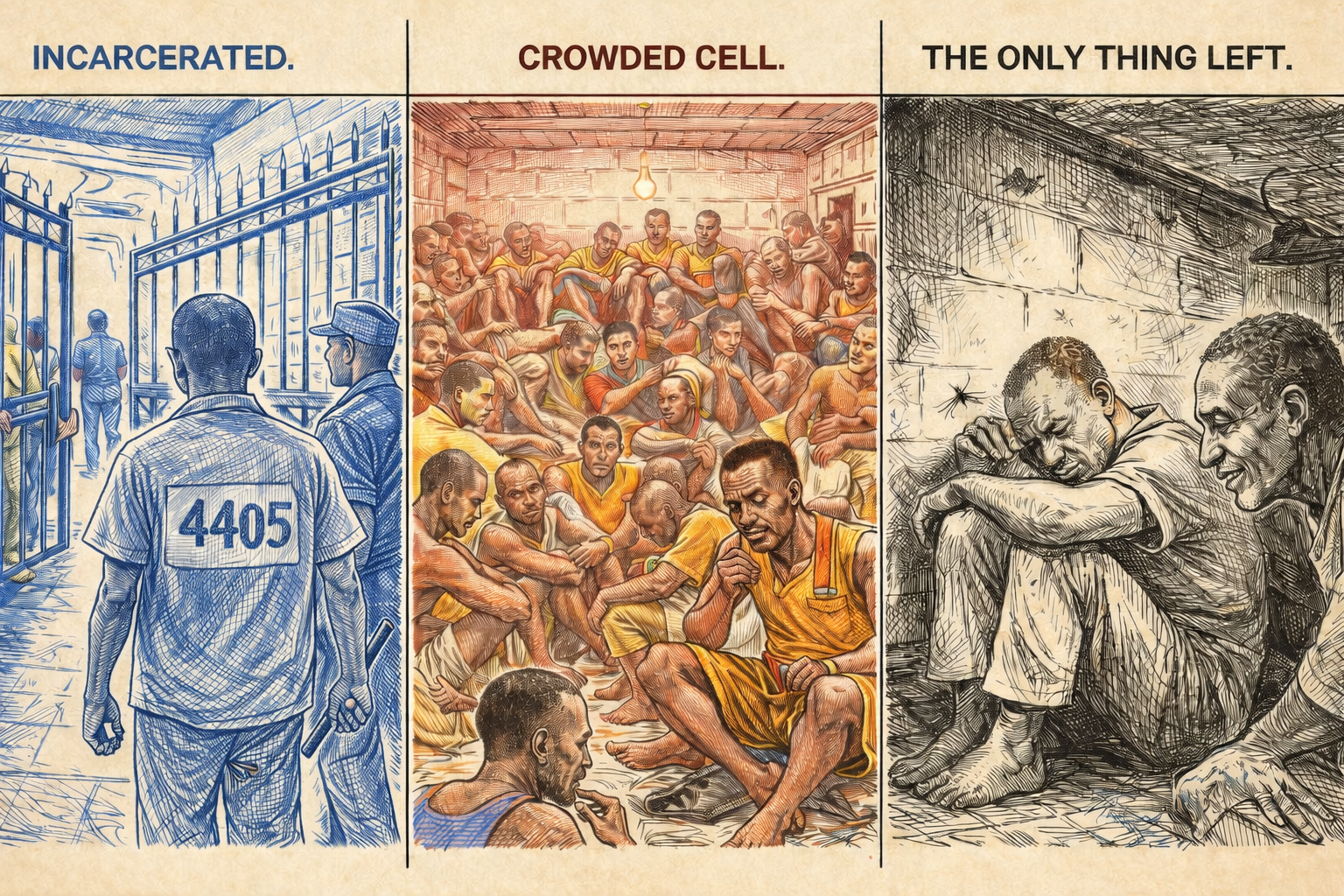

A hush fell over the room as Kwesi was led in. He was handcuffed and flanked by two-armed policemen. He looked gaunt, the stress of the last few weeks etched into his face, but he held his head high. As he passed the family, his eyes met Abena’s. For a moment, the world narrowed down to just the two of them, a silent exchange of love and despair.

“All rise!” the clerk bellowed.

The Judge entered, a stern woman with a reputation for expediency. She took her seat, and the case was called.

“The State versus Kwesi Dankwa.”

Kwesi stood in the dock. “Not Guilty, Your Honour,” he said, his voice steady despite the tremor in his hands.

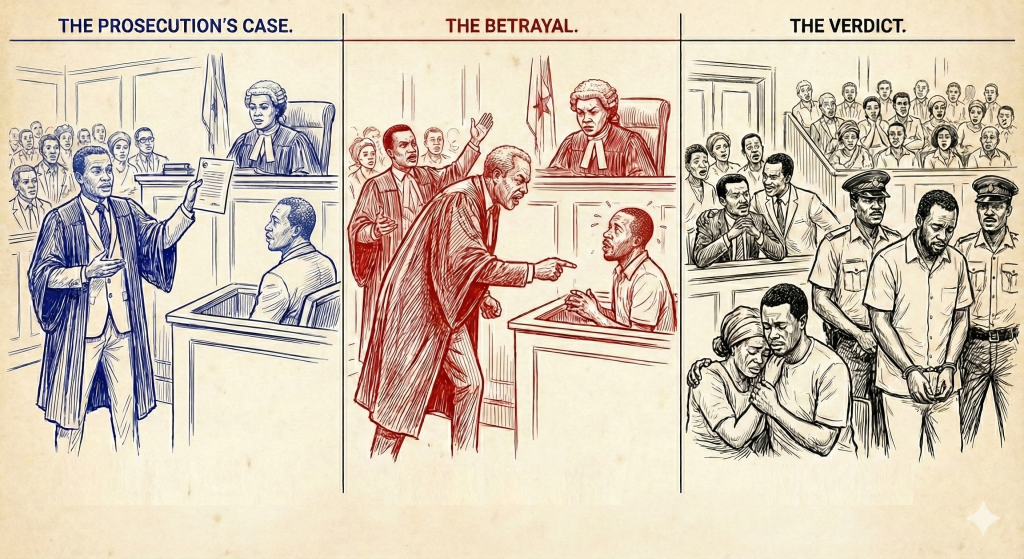

Jude Asamoah rose for the prosecution. He looked every inch the rising star: impeccable, articulate, and utterly ruthless. “Your Honour,” he began, “we will show that this man, entrusted with the nation’s wealth, chose instead to enrich himself.”

He called his witnesses. First, a representative from the Ghana Building Authority, then a Ghana Vehicle Registration Commission official, then a bank manager. They were honest men, confirming the authenticity of documents, documents that had been meticulously forged by Kojo’s network. One by one, they confirmed the documents. Yes, the land was bought in Mr Dankwa’s name. Yes, the cars were registered to him. The paperwork was impeccable. The evidence was damning because it was official.

Kwarteng cross-examined them, trying to find a flaw. “Is it possible,” Kwarteng asked the bank manager, “that an account could be opened without the physical presence of the account holder, if one had the right… connections?”

“Objection,” Jude said lazily. “Speculation.”

“Sustained,” the Judge ruled.

Then came the hammer blow. Jude called two truck drivers—the very same men Kwarteng had hoped to use for the defence. They entered the box, unable to meet Kwesi’s eyes.

“Tell the court,” Jude asked, “who instructed you to divert the cocoa shipments to the Ivory Coast border?”

The first driver swallowed hard. “It was… it was Mr Dankwa, sir. He gave us the waybills.”

Kwarteng shot to his feet for cross-examination. “You are lying!” he roared, losing his cool for a fraction of a second. “Two weeks ago, you told my investigator it was Kojo Danso!”

“I… I was confused then, sir,” the driver stammered, rehearsed lines slipping. “I remember better now. It was Mr Dankwa.”

“Who got to you?” Kwarteng pressed. “Who paid you?”

“Objection! Counsel is harassing the witness.”

“Sustained. Move on, Counsel.”

Jude rested his case. Lawyer Kwarteng stood up, his “K10PS” strategy now a tattered rag. He made a submission of “No Case to Answer”, arguing that the evidence was circumstantial and the witnesses unreliable.

The Judge leaned forward, adjusting her spectacles. “Counsel,” she said, “the prosecution has presented official government records and eyewitness testimony. The submission is overruled. The accused has a case to answer.”

Kwarteng called his witnesses. It was a parade of character and emotion against a wall of fabricated facts. Uncle Gyasi spoke of Kwesi’s Christian values. Auntie Esi wept as she recounted his kindness and honesty, how he had returned a bag with a laptop and money he found on campus when he was a student. Agorozo testified that Kwesi was one of few people at the Tema harbour who did not take bribes.

Then Mr Mensah took the stand. He tried to paint the bigger picture. “Your Honour,” Mensah said, his voice trembling with indignation, “Kwesi was building a digital system to stop theft. SMS tracking, mobile money. He was a threat to the corrupt elements in the company. That is why he is here! He is being framed by those who fear his integrity!”

“Objection!” Jude shouted. “Conspiracy theories without a shred of proof!”

“Sustained,” the Judge said boredly. “Mr Mensah, stick to facts, not wild accusations.”

Finally, Maame Serwaa, the local gossip and unofficial town spokeswoman of Bantama, took the stand. She did not have facts, but she had an audience. She cried, she wailed, she called down curses on the “real thieves”; she pointed fingers and called Kwesi the “son of Bantama”. Although her testimony lacked any legal significance, it was good for public consumption—good for radio and television and, more importantly, good to touch the maternal heart of the female Judge, just as Kwarteng had hoped.

Closing arguments were made. Jude Asamoah painted Kwesi as a greedy, modern criminal hiding behind a facade of respectability. Lawyer Kwarteng pleaded for the court to see the man, not the manufactured paper trail.

The court adjourned for two hours. When the Judge returned, the silence in the room was suffocating.

“Kwesi Dankwa, please stand,” the Judge said.

Kwesi stood, his legs shaking.

“On the count of Fraud, I find you Guilty. On the count of Causing Financial Loss to the State, Guilty. On the count of Smuggling, Guilty. On the count of Embezzlement, Guilty.”

A collective gasp went through the room. Abena buried her face in Osei’s shoulder, sobbing uncontrollably.

“You have abused your position and betrayed your trust,” the Judge continued. “The court sentences you to: five years for Fraud; five years for Causing Financial Loss; ten years for Smuggling; and twenty years for Embezzlement. Sentences to run concurrently with hard labour.”

Twenty years.

Kwesi felt the world spin. Twenty years. His life was over.

In the gallery, Kojo and Agyeman exchanged a look of pure relief. Osei held the weeping Abena closer, a dark satisfaction in his eyes. Mr Mensah sat with his head in his hands, a broken man. Uncle Gyasi stared blankly at the wall.

Jude Asamoah gathered his files, avoiding the gaze of the man he had just condemned. He had won. He was the hero of the hour. But as he walked out, the cheers of the crowd sounded strangely hollow in his ears.

Kwesi was led away, the handcuffs clicking shut on his wrists, sealing his fate. Kwesi Dankwa, the Golden Boy of Bantama, was no more. He was now just a number in the system. The Golden Return had become a journey into the abyss.