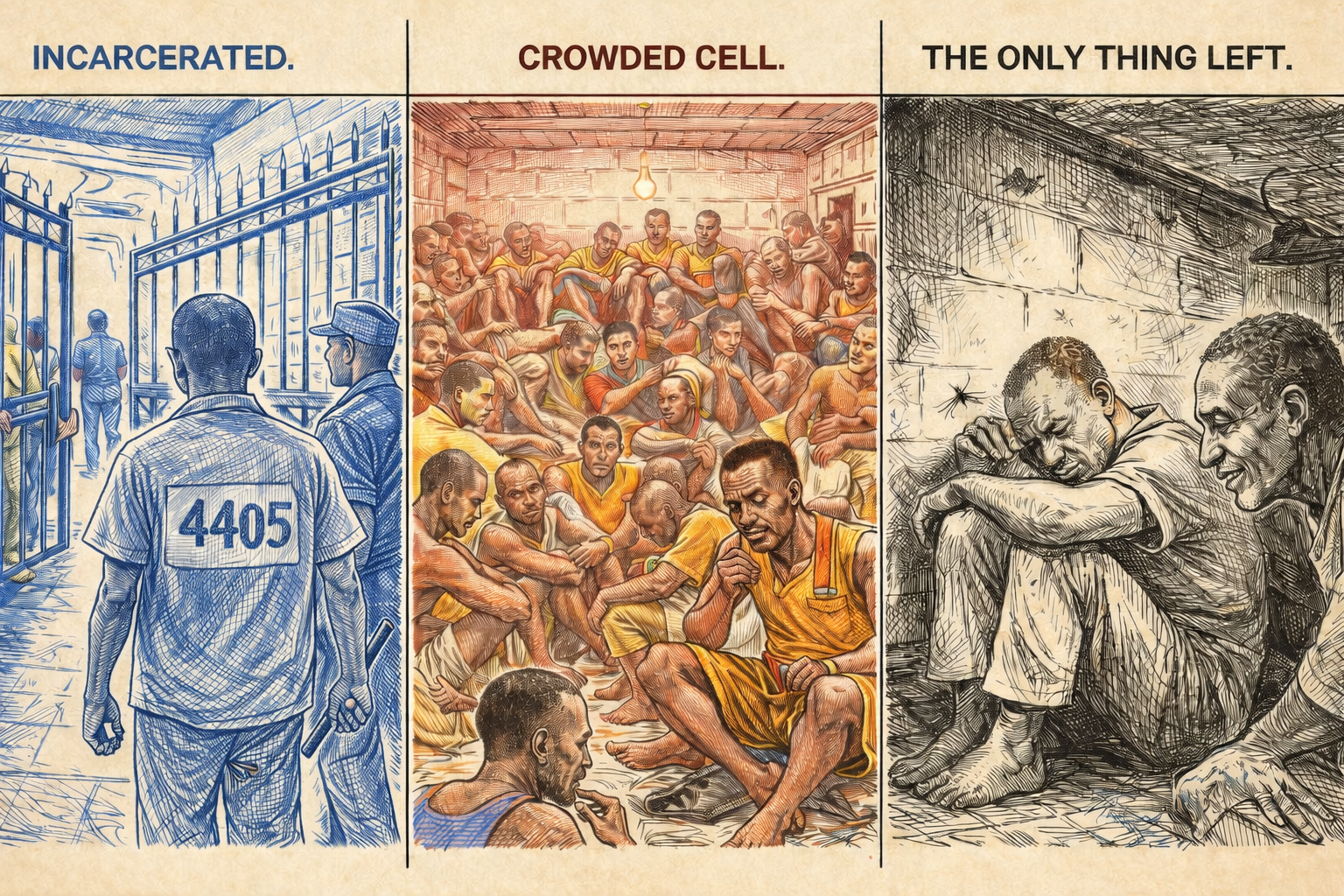

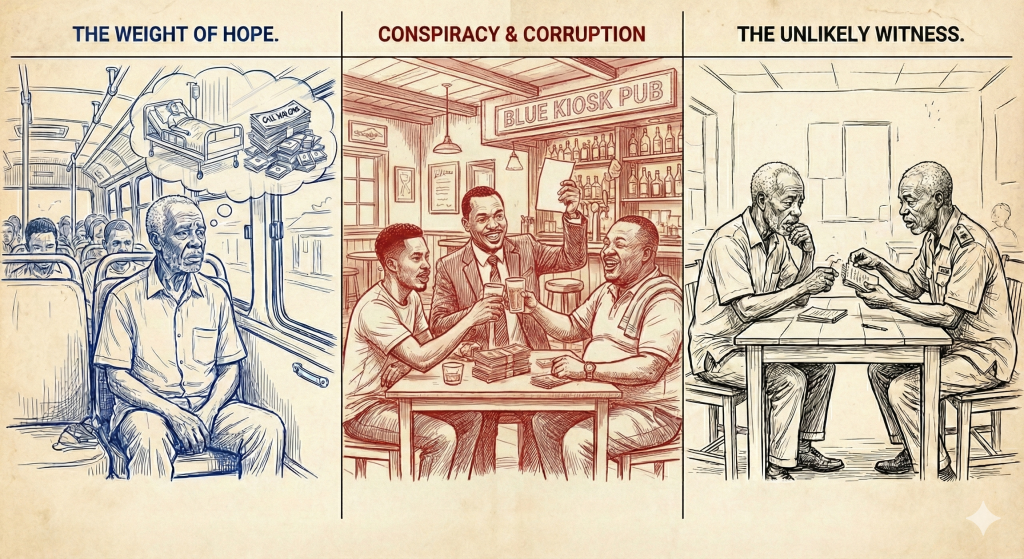

Uncle Gyasi sat in the middle row of the STC bus as it rumbled out of the Asafo terminal, leaving the chaos of Kumasi behind. The air conditioning was a welcome relief from the heat, but it did nothing to cool the fever of anxiety burning in his chest. After the devastating blow to Mr. Mensah, the mantle of hope had fallen squarely on his shoulders.

Yesterday afternoon, he had visited Kwesi at the police station with Osei. Despite the gloom of the cell, Kwesi had managed to scribble down eighteen names—men and women in Tema he believed were honest, people who might have seen something. Gyasi had asked Osei to accompany him, thinking two heads were better than one, but Osei had demurred, citing a job interview. Gyasi couldn’t press him; the boy had struggled enough. He had wished him well, not noticing the flicker of relief in Osei’s eyes.

As the bus passed the township of Ejisu, Gyasi’s thoughts turned to Opanyin Dankwa lying in the hospital bed. Three hundred thousand Ghana Cedis. The sum felt heavy enough to sink a ship. He had rallied the family, squeezing contributions from aunts, cousins, and distant relatives. They had raised GHS 210,000, a testament to their love, but still short. Even Osei, jobless as he was, had chipped in GHS 200, a gesture that touched Gyasi deeply. Mr. Mensah had offered to help, but Gyasi knew the man was already bleeding money for legal fees. The Oforis were feeding Kwesi twice a day; he couldn’t ask them for more.

Now, he needed to find GHS 90,000. It was a mountain to climb, but for his brother, he would climb it barefoot.

The bus pulled out of the Bonsu rest stop after a short break. The rhythmic hum of the engine lulled the exhausted man into a fitful sleep.

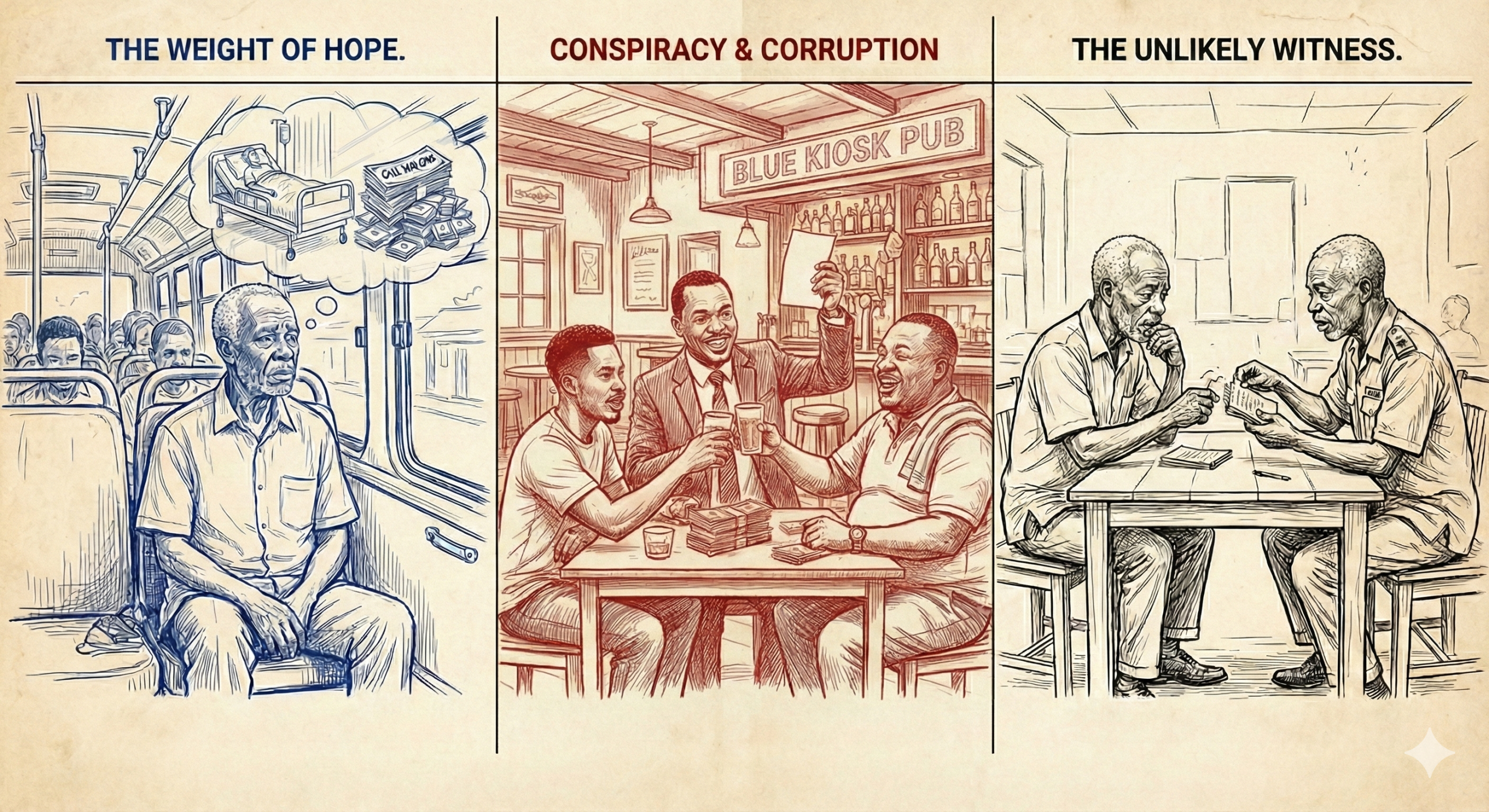

At the same time, miles away in the heart of Kejetia, the Blue Kiosk was buzzing. The unholy trio of Kojo, Agyeman, and Osei were gathered at their usual table. The air was thick with the smell of kebabs and triumph.

“To the new Regional Director!” Kojo announced, raising his glass of Guinness. His smile was wide, oily, and triumphant. “The board saw the light. Mensah is out. Indefinite leave. Which, as we know, means forever.”

“Director Danso,” Agyeman chuckled, clinking his beer bottle against Kojo’s glass. “It has a nice ring to it.”

Osei took a long pull of his drink. “And Kwesi?”

“Buried,” Kojo said dismissively.

“Good,” Osei muttered. “But listen, his Uncle Gyasi… he went to Tema today. Kwesi gave him a list of names.” Osei pulled out his phone and showed them a picture he had surreptitiously snapped of the list in the police station.

Kojo glanced at it and waved a dismissive hand. “Low-level clerks. Drivers. Nobody. I’ll make a few calls. By the time the old man gets there, they’ll be useless.”

“Don’t forget my office job,” Osei reminded him, his eyes hard. “I did my part. I want to sit in AC too.”

“Patience, Osei. Let the dust settle. You’ll get your desk.”

Agyeman leaned in, wiping sweat from his brow. “And Lawyer Kwarteng’s investigator? He’s been sniffing around Bantama. Asking about the cars, the houses… the things we said Kwesi bought. If he finds out Kwesi doesn’t own a single block…”

“Relax, shopkeeper,” Kojo soothed him. “I have connections at the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Authority. By next week, there will be papers with Kwesi’s name on them. Papers for cars he’s never seen. The evidence will exist because we will create it.”

“And my imports?” Agyeman pressed.

“Soon. Once I have the keys to the kingdom fully in my pocket, the containers will flow. For now…” Kojo reached into his pocket and pulled out a thick envelope. He slid some notes to Osei and Agyeman. “For your troubles. Go and enjoy.”

They parted ways into the night, three men bound by secrets and paid in smuggled cocoa money.

Uncle Gyasi arrived in Tema late that evening. Auntie Esi met him at the station, her face etched with worry. Over a dinner of kenkey and fish that Gyasi could barely touch, they discussed the elephant in the room: the GHS 90,000.

“If we don’t get more contributions by the time I leave,” Gyasi said heavily, “we may have to sell a few acres of the family cocoa farm in the village.”

It was a desperate measure; selling family land was a hard choice to make, but Opanyin Dankwa’s life hung in the balance. Gyasi went to bed with a prayer on his lips, hoping the morning would bring answers, not more dead ends.

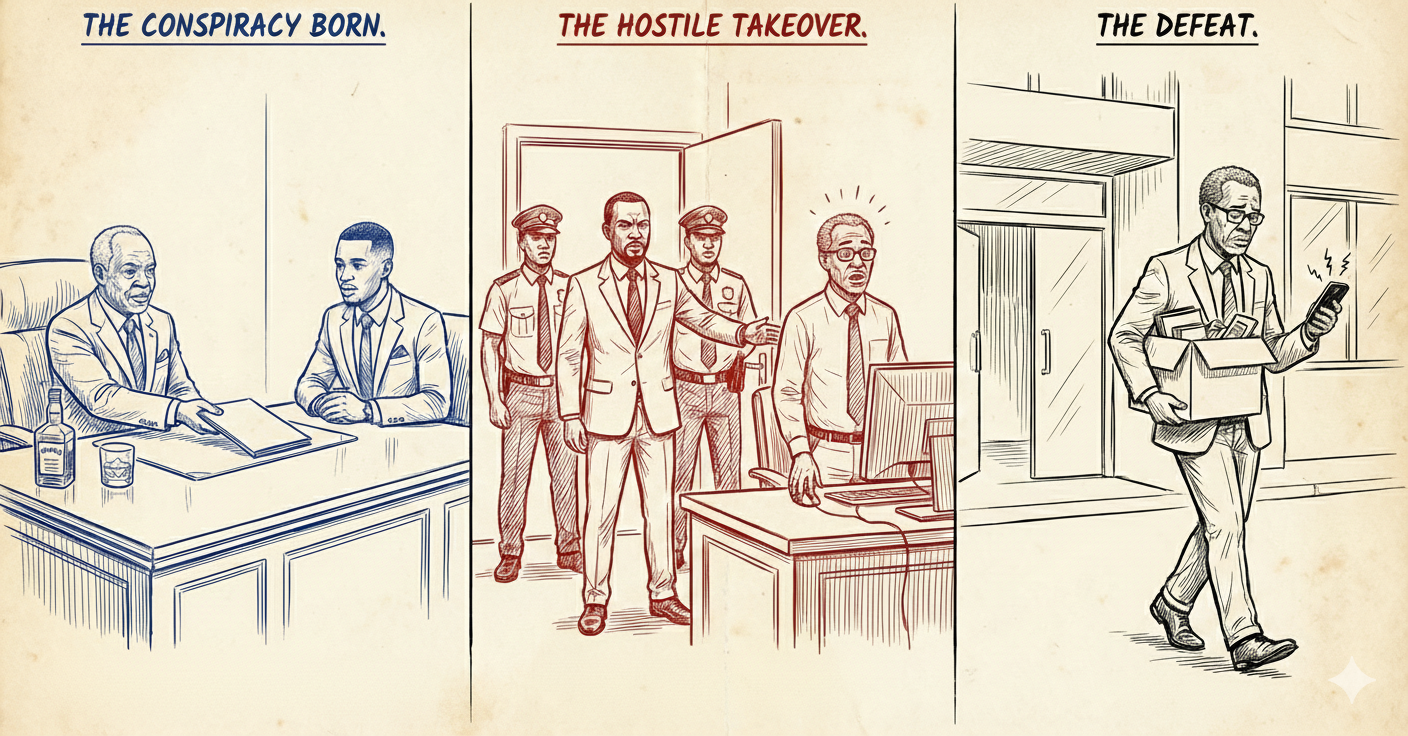

By 2 PM the next day, Uncle Gyasi sat at the “Good Wife Chop Bar,” a bowl of fufu and light soup cold and untouched before him. He was exhausted, frustrated, and on the verge of despair.

The morning had been a disaster. Kojo’s reach was long. Of the eighteen names on the list, fourteen were dead ends. “Transferred to Takoradi.” “Gone on leave.” “Sorry, I can’t talk to you.” People looked at him with fear in their eyes and hurried away. Three numbers were disconnected.

His last hope was Philip Amartey, popularly known as Agorozo. He was supposed to meet him here thirty minutes ago. Gyasi stared at the clock on the wall, watching the seconds tick away his nephew’s freedom.

Ten minutes later, a man in his fifties walked in. He wore a faded security uniform and walked with the heavy tread of a man who had carried too many burdens. He scanned the room, spotted Gyasi, and sat down opposite him.

“You must be Kwesi’s uncle,” he said, his voice gravelly.

“I am,” Gyasi said, sitting up straighter. “You are Agorozo?”

“That is me. I’ve been at this harbour for thirty years. Loading boy, cleaner, security, and now container checker. I see everything.”

Agorozo sighed. “You are fighting giants, old man. A memo went round this morning. ‘Internal restructuring.’ People are being moved like pawns. Transfers, forced leave. They are scrubbing the place clean.”

Gyasi’s heart sank. “So it was for nothing.”

“Maybe. Maybe not,” Agorozo said. He leaned in closer. “I like your nephew. Kwesi is a good boy. A few months ago, my wife was sick. Malaria, bad. I didn’t have a pesewa. Kwesi paid the bill. Didn’t ask for a loan, just paid it. He didn’t know me from Adam.”

He reached into his worn bag and pulled out a notebook with dog-eared pages.

“You need facts, right? The lawyer needs something real.” Agorozo licked his thumb and flipped through the pages. “I keep records. My own records. Force of habit. I note down trucks that look… heavy. Or leave at odd hours.”

He tore a few fresh pages from the back and began to write, copying numbers and dates from his logs. The scratching of the pen was the only sound at the table. Forty minutes later, he handed the bundle of sheets to Gyasi.

“Here,” Agorozo whispered. “These are the registration numbers of every truck that left the cocoa shed off-schedule during the weeks Kwesi was here. I don’t know who owns them, but if you trace these plates… you might find something.”

Gyasi took the papers, his hands trembling. It was a list of codes, meaningless to him, but perhaps the key to everything.

“Thank you,” Gyasi breathed. “God bless you.”

“Give it to the lawyer,” Agorozo said, standing up. “Maybe it helps. Maybe not. But it’s the truth.”

As Agorozo walked away, Uncle Gyasi looked at the papers. It wasn’t a smoking gun, but it was a bullet. He would leave Tema with something. All was not lost.