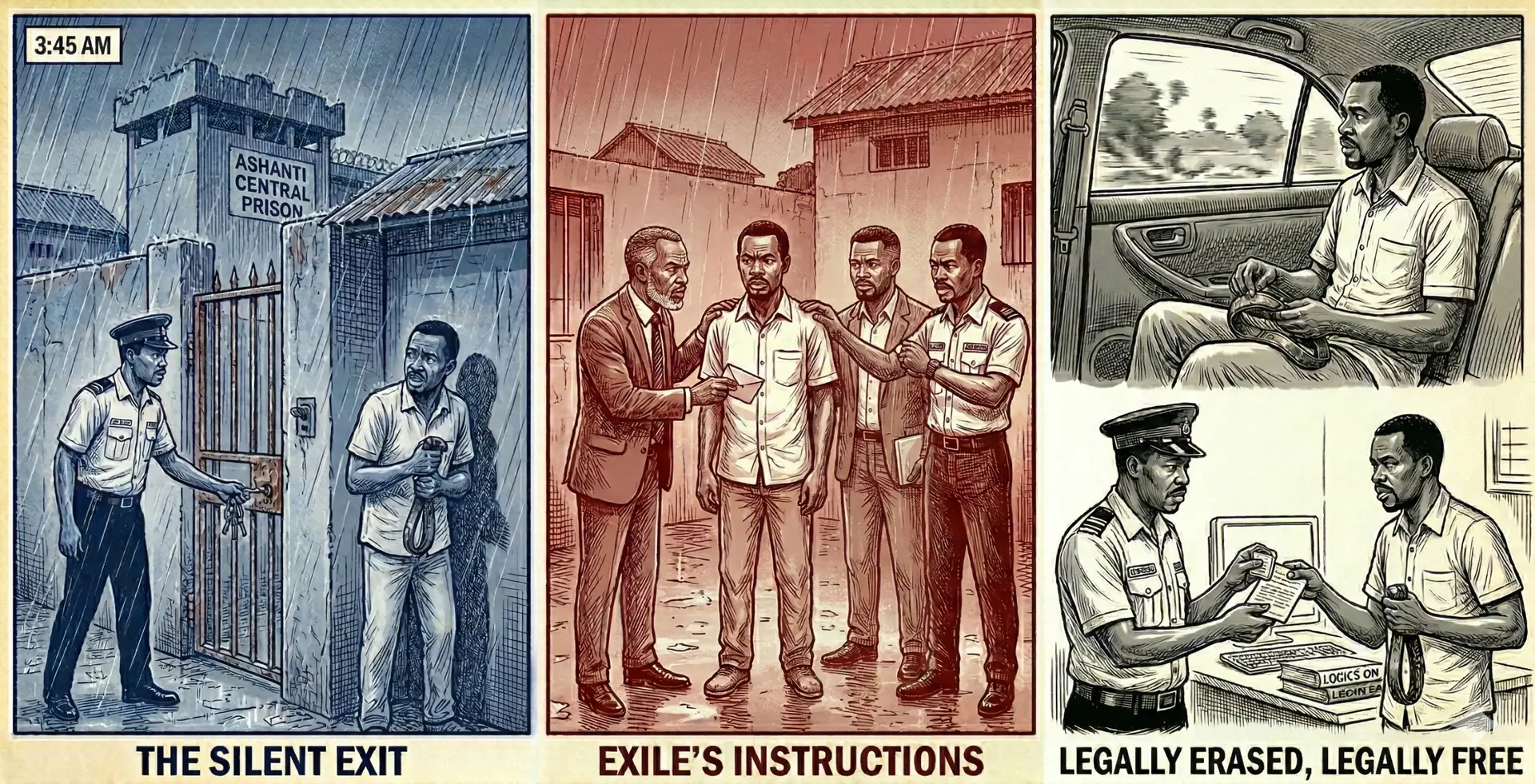

The morning sun hadn’t yet burned off the mist hanging over the Sofoline Police Station when a courier motorcycle skidded to a halt at the front gate. The rider, a young man with a helmet obscuring his face, handed a thick, sealed envelope to the officer on duty.

“Urgent delivery for the Chief Inspector,” the rider said, his voice muffled. “From the Attorney-General’s office.”

It was a lie, of course, all part of Kojo’s meticulous planning, but the official-looking seal and the mention of the Attorney-General were enough to wake the officer up. He rushed the envelope inside.

Chief Inspector Amidu was just settling in with her morning tea when the envelope landed on her desk. She tore it open. Inside was not just a letter, but a detailed dossier. Shipping manifests, dates, times, and a covering letter that accused Kwesi Dankwa of masterminding a massive cocoa smuggling ring. The letter claimed Kwesi was a flight risk, planning to use his new position to flee the country after a “sham” engagement ceremony.

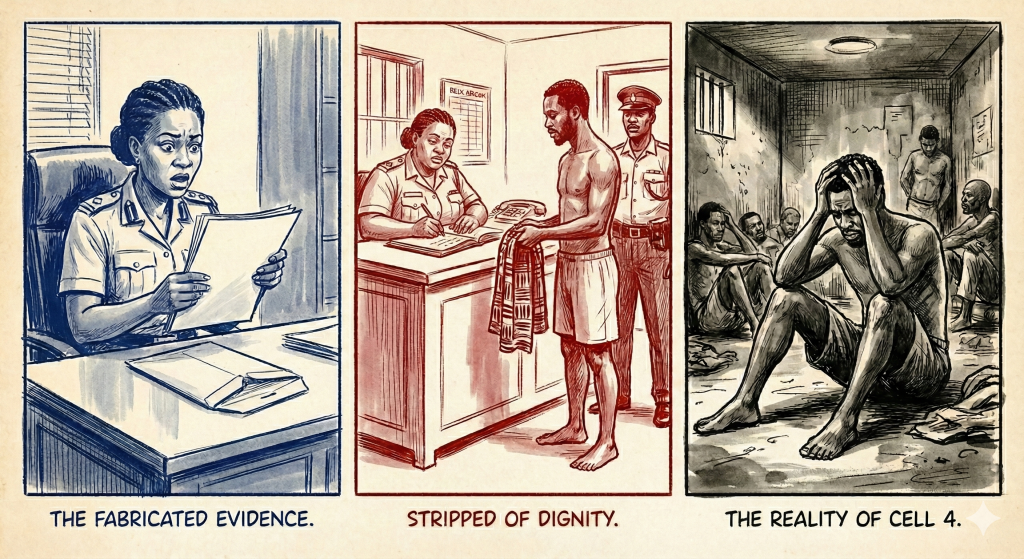

“Smuggling? Fraud?” Chief Inspector Amidu’s eyes widened as she scanned the fabricated evidence. It looked legitimate. Damn legitimate. And if this was true, it was the kind of bust that got one promoted to Accra.

She didn’t hesitate. “Sergeant!” she bellowed. “Get a team ready. Two pickups. Armed. We have a big fish to catch.”

“Where to, Madam?”

The Chief Inspector glanced at the letter, where Osei had helpfully provided the address and time. “Patasi. A house near the Brother Man Pub. We move now.”

An hour later, the police team were on their way back to the station, sirens wailing, cutting through the Saturday morning calm like a knife, with their big fish.

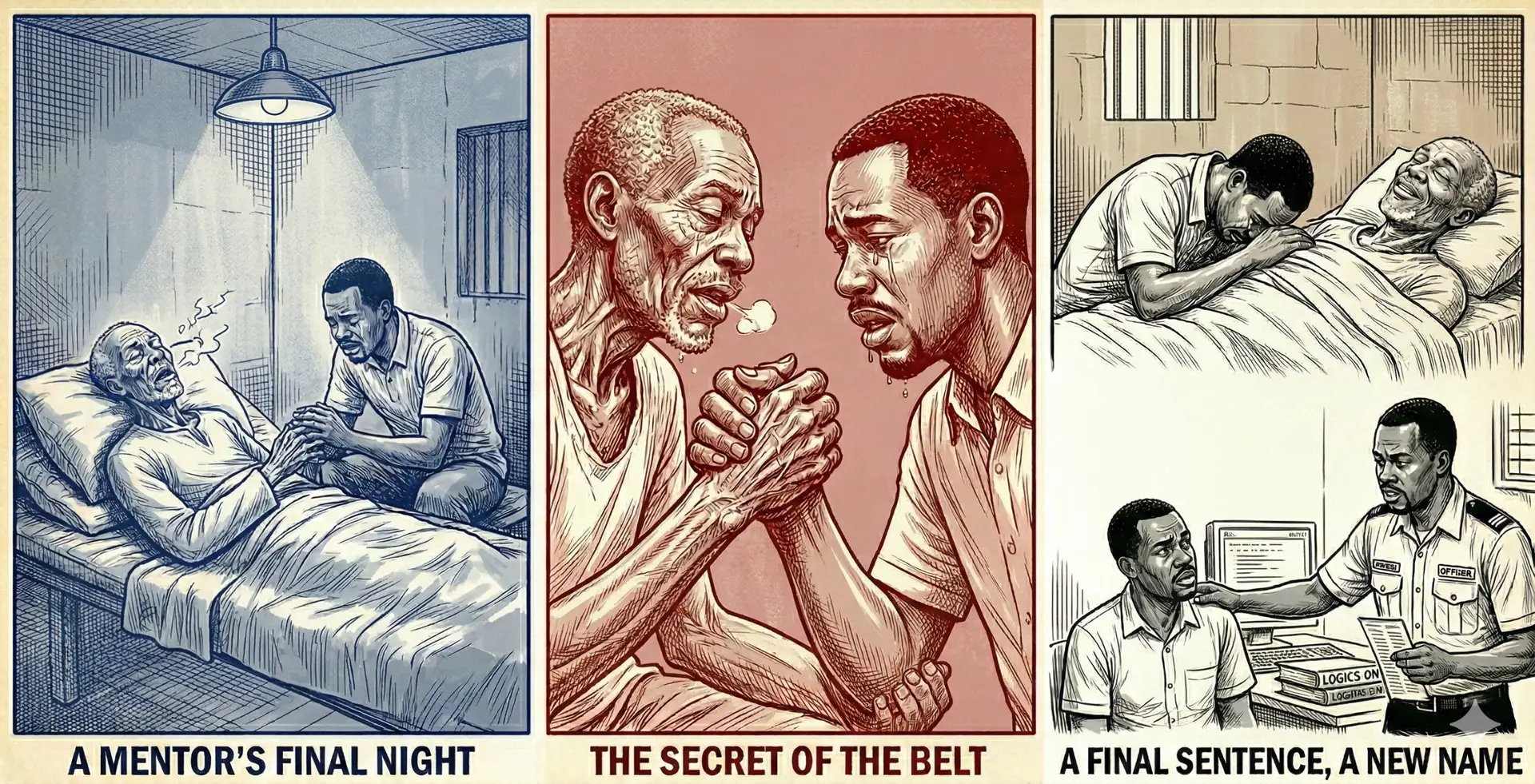

Inside the lead pickup, the air conditioning wasn’t working, or perhaps the officers didn’t care to turn it on. The heat was already building. Kwesi, now squeezed into the back seat between two burly officers, felt it pressing down on him, a physical weight matching the terror in his chest.

He looked down at his wrists. The cold steel of the handcuffs bit into his skin, a jarring contrast against the rich weave of his white and blue kente. Just an hour ago, this cloth had been a symbol of his ascent; now, bunched up and wrinkled, it felt like a shroud.

“Officer, please,” Kwesi tried again, his voice sounding foreign to his own ears, stripped of its usual confidence. “There has been a mistake. A terrible mistake. I am Kwesi Dankwa. I work with Ashanti Cocoa Buying Company. Ask Mr. Mensah. Just let me make a call.”

The officer on his right, a man with a scar running through his eyebrow and eyes that had seen too much of Kumasi’s underbelly, laughed. It was a dry, humourless sound.

“Mr. Dankwa,” he mocked, dragging out the title. “Everyone in handcuffs is innocent. Everyone has a big man to call. But the paper we have says you are a thief. A big thief.”

“I am not a thief!” Kwesi snapped, the injustice of it igniting a spark of his old fire. “I am due to be the Regional Director on Monday!”

“Director?” The driver chuckled, catching Kwesi’s eye in the rearview mirror. “Well, Director, today you are directing yourself to the police station. Maybe you can manage the mosquitoes in the cell. They are very unruly.”

The car swerved around the Sofoline interchange, the tires screeching. Through the tinted glass, Kwesi watched the city roll by. It was the same Kumasi he had traversed yesterday, the hawkers, the yellow taxis, the vibrant chaos, but it looked different now. Distant. Unreachable. He saw men in ties walking briskly, women laughing, people living their lives with the freedom he had taken for granted only this morning.

He thought of his father, collapsing into Uncle Gyasi’s arms. The image burned behind his eyes. He thought of Abena, her white lace dress standing out in the crowd, her scream echoing in his head.

They arrived at the police station. The pickup jerked to a halt. The officers hauled him out, not gently. The spectacle of a man in full ceremonial kente being dragged into the charge office drew stares from the people loitering outside. Kwesi kept his head down, the shame burning his neck like a physical brand.

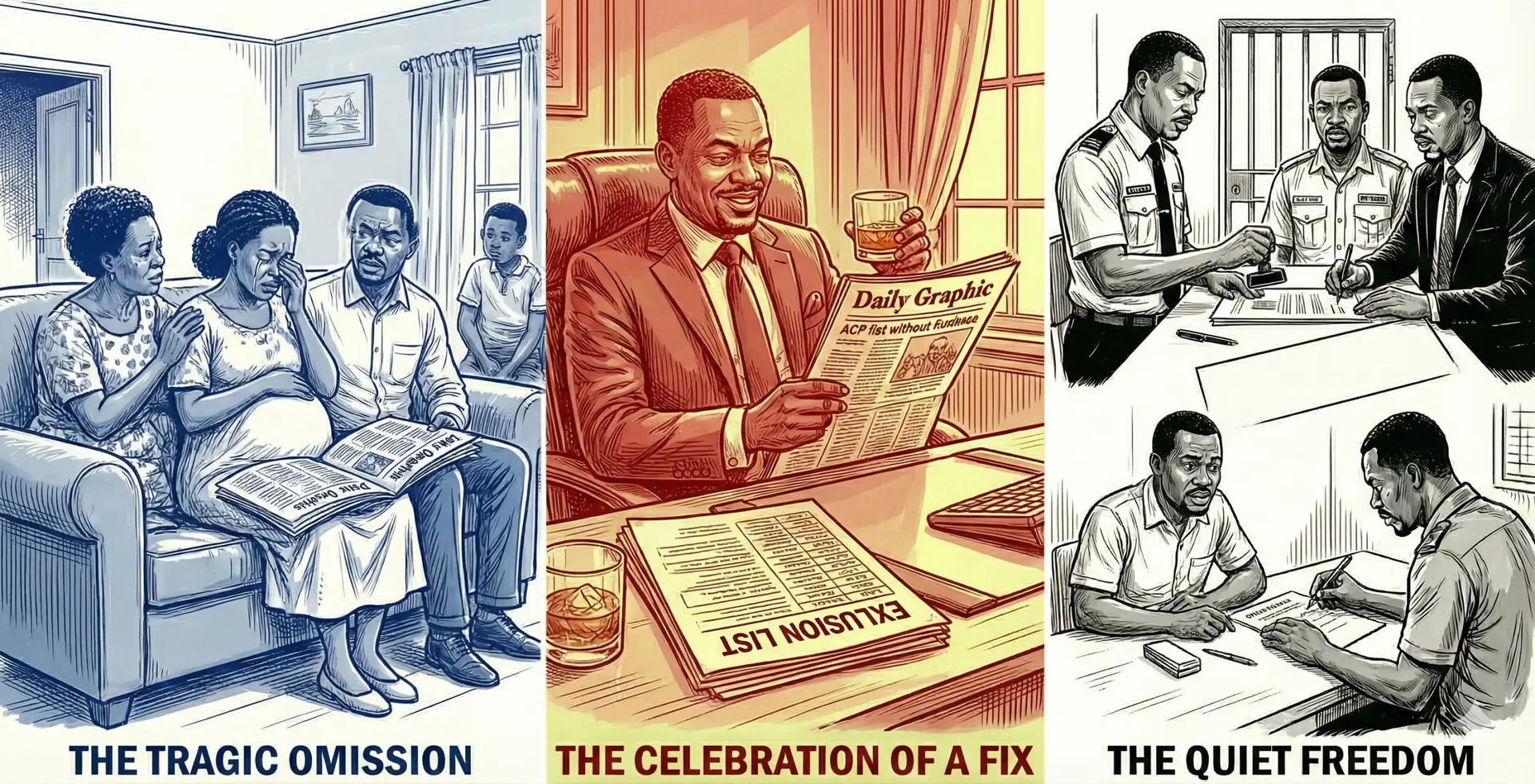

Inside, the noise was a physical assault. Shouts of arguing people and ringing phones filled the air. He was pushed towards the high wooden counter. The desk sergeant, a large woman with an air of absolute boredom, looked up slowly.

“Name?”

“Kwesi Dankwa.”

“Offence?”

The arresting officer slapped the file—the very file the Chief Inspector had opened that morning—onto the counter. “Fraud. Smuggling. Causing financial loss. CI ordered it herself.”

The sergeant raised an eyebrow, finally looking at Kwesi with a flicker of interest. “Ei. Kente and all. You dressed up for us?”

“I was at my knocking ceremony when they arrested me,” Kwesi said, his voice barely a whisper.

“Well, the lady is lucky then,” she muttered, opening a ledger book. “Empty your pockets.”

Kwesi hesitated. His hands were still cuffed. The officer unlocked one wrist, allowing him to awkwardly dig into his pockets. He placed his items on the scarred wood of the counter: his leather wallet, his smartphone, a handkerchief, and the watch he had bought to celebrate his first salary when he was employed five years ago.

The sergeant catalogued them slowly. “One watch, silver colour. One phone, cracked screen…”

“It wasn’t cracked before,” Kwesi protested.

“It is cracked now,” she said flatly, writing it down. “Take off the sandals. And the cloth. You can’t wear that inside.”

“Take off… my cloth?” Kwesi felt a fresh wave of humiliation. Underneath, he was wearing only his shorts. “Madam, please.”

“You want to wear kente in the cell? The boys will tear it to make blankets. Take it off.”

Slowly, with trembling fingers, Kwesi unwrapped the beautiful cloth. He folded it as best he could, handing over the symbol of his dignity. He stood there, shivering in the draft of the fan, stripped down to his basics, stripped down to nothing.

“Cell 4,” the sergeant ordered.

As the officer led him away, barefoot on the cold, grimy floor, towards the iron-barred gate that separated the free from the condemned, Kwesi realised the terrifying truth. The logic of the boardroom, the rules of fair play, the meritocracy he believed in—none of it applied here. He had stepped into a different world, and he didn’t know the rules.

Behind him, in the Chief Inspector’s office, the anonymous letter sat on the desk, its work for the day done. But its journey was just beginning. Monday morning, it would find its way to an even more dangerous desk: that of Justice Asamoah.